Hearth to Hearth: Boarding Houses – The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles – March 2003

The American boarding house is a relic of the first stages in the growth of large cities. Young men coming off the farm and looking for city jobs needed some kind of sheltering environment, and the boarding house family offered that. For a reasonable sum, one could find a room (though not always private), meals (hopefully good), and sometimes laundry. In addition, in those early days the boarding-house keeper might take the lad under her wing, indoctrinate him into the manners and methods of city life, take him to church with the rest of her family, and exert a strong moral or political influence on him..

This was a new style of home away from home for the boarder, and for the keeper it was an equally ground-breaking step. Boarding-house keepers were often married, middle-class, urban women who needed to earn an income. This put her in contradiction to the current social ideal; by assuming the male role and earning money she was considered by many of her peers to be a shameful embarrassment.

However, for a widow left destitute with few resources apart from a large house, taking in lodgers was a logical intermediate solution. Working at home and capitalizing on her domestic skills, she did not seem quite as scandalous to her community as she might have been working in a more public factory, office, or shop, and she may have been able to maintain something of her social position.

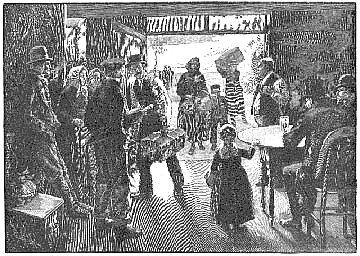

As cities grew, people sometimes adapted to new living arrangements of an entirely different cast. In the 1820s and ‘30s, the early textile mills on Massachusetts’ Merrimack River set up company towns and controlled even the housing. The Lowell Mills, seeking to attract a responsible group of young women with reassurances to their families about safety and morality, established an innovative series of strictly-chaperoned boarding houses, often accommodating up to thirty women, sometimes six to a bed. Everything functioned around the factory bell system: the girls rose early for a hearty breakfast that included meats, fish, potatoes, and porridge and scurried off to work by the first bell. At noon the dinner bell announced the meal break, and the girls flew across the street to their accommodations (deliberately placed near the factories to save time), and raced through the dinner already set out family style on the dining room table. Another bell announced the resumption of work, and finally the evening bell released them to return home for the only leisurely meal of the day, their supper.

The boarding-house keepers’ lives were no easier—they were hired by the mill owners not only to chaperone but also to provide food and laundry, and in fact they competed for their lodgers on the quality of their tables. Many of these genteel widows adapted to the system, but others were unsuccessful and did not function well with “masculine” business roles. Forced to work to support their children, they sometimes could not compromise their life-time standards, overspending on “nice” foods, and losing the profit for which they worked so hard.

The first waves of immigration demanded another kind of boarding house. Newcomers unable to speak the language and unfamiliar with American working conditions needed a a transitional kind of place in which they could gradually learn the ropes. They tended to seek room and board with family or countrymen whose language, customs, and cuisines were familiar. Jews who required kosher food were certainly limited to these kinds of arrangements; but just the comfort of being with someone who could joke in the same vernacular, or a special dish from the old country must have been immensely comforting. Some told stories of bedding down in the kitchen, sharing rooms and beds with strangers, and many an awkward or lonely moment as they worked toward establishing themselves.

Another kind of arrangement was sometimes the factor of a shared profession. Under the old apprenticeship system, the master of a shop took in young trainees, and in exchange for whatever work they did, they were paid in the room and board that was customarily supplied by the master’s wife. Sometimes someone who ran a small shop lodged an employee—for example, a milliner may have kept her young assistant, particularly if she had come from some distance to work in a town where no other suitable accommodations were to be found.

The end of the nineteenth-century brought an entirely different kind of arrangement—the summer boarding house. This did not offer year-round accommodations for the poor, the unacculturated, or the factory hands, but instead attracted the more affluent to respite from the summer heat. Entire families could take up temporary residence at the seashore or in the mountains, to enjoy buccolic or salt-water pleasures. When possible, women and children stayed all summer, and the men joined them for weekends. Those of lesser means enjoyed such vacations, but of only a week or two duration. Many returned each summer to the same boarding house, enjoyed the continuity, and the social contact with the keeper’s entire family. The keeper herself ran the kitchen and supervised the laundry, possibly handled by her older daughters; her husband may have maintained the large fruit and vegetable garden and the barnyard that fed the guests abundant and wholesome and fresh foods, simply cooked and baked. Hosts often organized and facilitated amusements for their guests, among them berry picking expeditions, fishing trips, and ice-cream parties that filled the summer days. The family that kept such a boarding house worked incessantly through the vacation months, but sometimes made enough in that short time to set up their children in business, to send them to college, or to keep everyone in a more leisurely style through the winter.

As the cities grew, they also responded to the needs of people with like needs and interests. For example, boarding houses sprung up for artists alone, actors, or musicians. A group of “Grahamites,” vegetarians following the dietary principles of “nutritionist” Sylvester Graham congregated in Graham boarding-houses, where they could depend on appropriate food and like-minded company.

Other boarding houses catering to the rich and famous were run by women who had once enjoyed a higher position. Their stock in trade was their knowledge of fashionable furnishings, table, and manners. Such accommodations attracted many single people who preferred the company and accoutrements of their own class; in addition young newly-weds may have spent some years in this comparative leisure before “settling down to housekeeping” and starting families in their own homes.

The boarding-house institution became so common and its peculiarities so well known that it became the target of popular humor. Thomas Butler Gunn wrote a marvelous semi-spoof entitled The Physiology of New York Boarding Houses (1857) in which he caricatured the petty, the eccentric, the dramatic, the hypocritical, and the objects of prejudice. Among his essays were “The Poor Boarding-House,” “The Serious Boarding-House,” “The Fashionable Boarding-House Where You Don’t Get Enough To Eat,” (“for lunch you get pie, delicate shavings of cold meat, and coffee”); “The Medical Students’ Boarding-House,” “The German ‘Gafthaus’” in which lodgers were portrayed as “subsisting exclusively on sour-krout and lager-bier;” “The Irish Immigrant Boarding-House (As It Was),” “The Sailors’ Boarding-House” and “The Boarding-House Which Gives Satisfaction To Everybody” (the page deliberately a blank).

In the twentieth century these parodies were still going strong. Major Hoople, the protagonist of a 1930s comic strip entitled “Our Boarding-House,” was a large, opinionated and blustery man who made a profession of avoiding work; his long-suffering wife ran the boarding-house that was, needless to say, filled with similar wastrels and pranksters.

In my own youth, boarding houses were still common spoofing material: we sang this song:

In the boarding-house where I liveEverything is green with mold,

Grandma’s hair is in the butter,

Silver threads among the gold. When the dog died we had hot dogs

When the cat died, catnip tea,

But when the landlord kicked the bucket,

Oh, that was too much for me—I don’t like hash …

Needless to say, the boarding-house recipe I am about to give you is not hash, although that was a common and sometimes frugal dish. Instead, I will offer one for New England Boiled Dinner, the kind of easily cooked and easily-served meal that the boarding-house keeper at Lowell, Massachusetts, might have set out for her mill girls. It had the advantage of being inexpensive, as the cut of meat used was preserved beef, and the root vegetables accompanying it were cheap, easily stored, and available year-round. But leftovers, if there were any, might have been ground into a hash and served for breakfast the next morning.

Recipe:

This version of New England Boiled Dinner comes from Harriet Beecher’s Domestic Receipt Book, New York: 1856, under the name “To Boil Corned Beef.” As her own background was New England, the regionality may not have seemed an important distinction to include in the title. As earlier versions of this dish are elusive, it is possible that New England Boiled Dinner was a 19th-century development. Only much later did this dish become the Irish icon for Saint Patrick’s Day, and then it was probably eaten more in America than it had been in Ireland. You will notice that Beecher expected people to be familiar enough with this kind of recipe so that she did not think it important to recommend amounts. Subsequent versions from twentieth century cookbooks have been more precise, and have also added turnips and parsnips. Feel free to experiment with quantities, according to the size of your crowd.

To Boil Corned Beef

Put the beef in water enough to cover it, and let it heat slowly, and boil slowly, and be careful to take off the grease. Many think it much improved by boiling potatoes, turnips, and cabbage with it. In this case, the vegetables must be peeled, and all the grease carefully skimmed as fast as it rises. Allow about twenty minutes of boiling for each pound of meat.

Alice Ross brings 25 years as a dedicated food professional teacher, writer, researcher and collector to her Hearth Studios, at which she teaches workshops in various aspects of hearth, woodstove and brick oven cookery. She has served as consultant in historical food for such noted museums as Virginia’s Colonial Williamsburg and The Lowell National Historical Park in Massachusetts. Ross wrote her doctoral dissertation in food history at the State University at Stony Brook. Currently, she is involved in a major kitchen report on Rock Hall Museum, a 1770’s Georgian mansion on Long Island. Dr. Ross’ e-mail address is aross@binome.com. Her web site is www.aliceross.com

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”SearchAndAdd” width=”550″ height=”200″ title=”More on Hearth cooking:” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”True” show_border=”False” keywords=”Open Hearth Cooking” browse_node=”” search_index=”Books” /]

Related posts: