The Hindenburg: A Disaster and a Miracle

by Mike McLeod

Seventy-seven years ago when the 803-foot Hindenburg crashed on May 6, 1937 at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Lakehurst, N.J., 35 people died: 13 passengers and 22 crew (including one on the ground crew). Fortunately, on that trip there were just 36 passengers on the airship. However, 61 crewmen were on board, many of them trainees. This was an epic tragedy and a miracle at the same time—nearly two-thirds of those on board survived the inferno.

On the National Postal Museum’s website [1] are videos of an interview with one of the original surviving members of the ground crew describing what he saw. Also, there is actual film footage of the Hindenburg burning and radio reporter Herb Morrison’s emotional commentary of the disaster:

“It’s practically standing still now. They’ve dropped ropes out of the nose of the ship, and it’s been taken ahold of down on the field by a number of men…. It burst into flames! Get out of the way! …It’s fire and it’s crashing! It’s crashing terrible! …It’s burning, bursting into flames and is falling on the mooring mast…. This is the worst of the worst catastrophes in the world! Oh, it’s crashing… oh, four or five hundred feet into the sky, and it’s a terrific crash, ladies and gentlemen. There’s smoke, and there’s flames, now, and the frame is crashing to the ground, not quite to the mooring mast… Oh, the humanity, and all the passengers screaming around here! [Morrison begins sobbing] I can’t even talk to people…. Honest, it’s just laying there, a mass of smoking wreckage, and everybody can hardly breathe and talk… I-I’m sorry. Honest, I can hardly breathe. I’m going to step inside where I cannot see it…. Listen folks, I’m going to have to stop for a minute, because I’ve lost my voice… This is the worst thing I’ve ever witnessed.” [2]

The Commerce Department Report on the Hindenburg Disaster stated: “The cause of the accident was the ignition of a mixture of free hydrogen and air. Based upon the evidence, a leak at or in the vicinity of cell 4 and 5 caused a combustible mixture of hydrogen and air to form in the upper stern part of the ship in considerable quantity; the first appearance of an open flame was on the top of the ship and a relatively short distance forward of the upper vertical fin. The theory that a brush discharge ignited such mixture appears most probable.” [3]

In the early 1900s, zeppelins were the futuristic way to travel. They cut in half the travel time across the Atlantic by ship. The arrival of an airship in New York City in 1928 was honored with a ticker-tape parade, and wherever they flew, people rushed into the streets to watch them slowly drift by (despite their cruising speeds being 70+ mph [4]). Flying on a zeppelin was akin to flying to the moon today—but with cruise ship-like comforts.

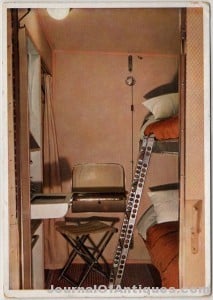

The Hindenburg featured fine dining, a grand piano in the lounge (that was not on the airship’s last flight) and even a smoking room—electric lighters were used, and a double airlock door secured it from other compartments. For added safety, it was located on the bottom level so any escaping hydrogen would travel upward and away from the smoking room. [5]

The Hindenburg Disaster has yielded items that are collected. Kovels.com reported that a bottle of Lowenbrau beer on the airship sold for $16,000 in 2009: “The Lowenbrau bottle, still full, has a scorched label with the brand’s logo. The bottle was found by the local fire chief after the crash in Lakehurst, New Jersey. He buried six bottles and a pitcher at the site and came back later to recover his ‘treasure.’ He gave all but one of the bottles to friends. One bottle was donated to the Lowenbrau brewery collection in 1977.”

Even though tickets for the Hindenburg were $450 each [6] during the Depression ($7,500 today), zeppelins also made a huge income by carrying mail. The Hindenburg had more than 17,000 pieces on board when it burned, and about 40 cents was charged to carry a letter [7]. That was equal to about $6.66 today; as a point of reference, during the Depression, a one pound of the best steak cost 20 cents [8].

Just over 300 pieces of mail survived the crash and fire, and today, individual letters can sell for thousands of dollars. Some even sell for tens of thousands of dollars depending on the stamps they bear, the franking and country of origin [9]. Of course, with values like these, fakes have been found.

Other Hindenburg items include coffee, cups, pot, silverware and even parts of the metal structure. Most are in museums or the Smithsonian, but sometimes, these items show up on eBay or in auctions.

On a side note, the Hindenburg was not the worst zeppelin accident in history. The USS Akron, a rigid Navy airship, crashed off the coast of New Jersey four years before the Hindenburg on April 4, 1933. Of the 76 crew and passengers on board, 73 died, most of them from drowning and hypothermia.

This disaster actually helped to save lives on its sister ship, the USS Macon, when it crashed in the Pacific in February of 1935. It carried lifejackets and inflatable rafts because of the Akron, and only two men died. As with many zeppelin accidents, human error was the major cause. On the Macon, structural failure punctured helium gas bags; however, it could have made it to base in this condition, except the officers and crew overcompensated by dropping ballast and increasing the engines’ power to gain lift. This propelled the airship above 4,000 feet where the low pressure sucked out too much helium for the ship to stay aloft. It drifted down into the ocean.

The Hindenburg Disaster will never be forgotten, but the miracle of so many people surviving the inferno should also be remembered.

Detailed information on the Hindenburg and other airships can be found at Airships.net.

1 – www.postalmuseum.si.edu/fireandice/videos.html

2 – Imdb.com

3, 4, 5 – Airships.net

6 – www.postalmuseum.si.edu

7 – www.slettebo.no

8 – Thepeoplehistory.com

9 – Ibid and Michel Zeppelin Specialized Catalogue 2003, by Michel

Related posts: