by Bill Thornbrook

Business travelers and vacationers today can expect a transcontinental flight from Boston or New York to Los Angeles or San Francisco to be more or less routine. But a century ago scheduled long-distance air service was still an elusive dream.

The very first trip across the country by airplane took place a few years after the Wrights’ December 1903 flight at Kitty Hawk. Calbraith Perry Rodgers held the controls of his new Wright bi-wing, “Vin-Fiz,” named for the popular grape-flavored soft drink that sponsored his flight. On September 17, 1911, the intrepid aviator launched his machine westward from the shore of Long Island. Nighttime, bad weather, accidents, mechanical failures, scheduled and unscheduled stops broke his flight into a series of short hops. Rodgers finally got into California after 49 days. Then one final crash delayed him from reaching the Pacific for another month.

Soon former World War I aviators were securing new government contracts for carrying the mail all over the country. They flew military surplus open-cockpit planes with sacks of mail stuffed into the forward seat as they piloted from the rear. Transporting letters and parcels paid well enough so there was little incentive to invite passengers aboard even if there had been more space. For ordinary civilians, then, flying long distances was not an available option.

That is until Clement Keys came up with a unique concept in 1928. An early advocate for the expansion of passenger air service, Keys was an investment banker and Curtiss Aeroplane Company executive. He already held a government contract for flying the U.S. air mail between New York and Chicago when he proposed an airline with a new mission. Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT) would serve primarily as a passenger service. But airplanes were only one part of Keys’ visionary plan.

To lay out a route across the country and oversee the construction of essential airfields and supporting facilities Keys hired Charles A. Lindbergh. The Lone Eagle had just the previous year made his solo flight across the Atlantic from New York to Paris. Now, “alone in my survey plane, in 1928, flying over the transcontinental air route between New York and Los Angeles, I had hours for contemplation,” Lindbergh recalled in his introduction to Apollo 11 astronaut Mike Collins’ 1974 book, Carrying the Fire. “Aviation’s success was certain, with faster, higher, and more efficient aircraft coming,” Lindy mused.

Both Lindbergh and Keys saw TAT as a further step in that process. The connection with the famous flyer would prove to be advantageous in attracting potential passengers. Once operational, TAT proudly promoted itself as “The Lindbergh Line.”

Affectionately described as the “Tin Goose,” the Tri-Motor did not present an elegant outward appearance. But it was safe and reliable. Its distinctive corrugated aluminum-alloy skin was fitted over a boxy metal frame nearly 50 feet in length with a fixed landing gear and a 78-foot wingspan. Its three 450-horsepower Pratt &Whitney engines carried up to 15 passengers and crew at 110 mph top speed, accompanied by bone-jarring vibration and deafening noise (Fig. 1).

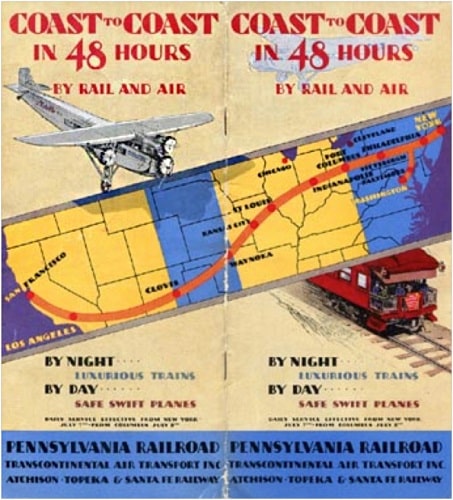

TAT’s inaugural trip got underway on July 7, 1929. The westward departure was not from an airport but from New York City’s Penn Station train depot. Patrons boarded a specially appointed Pennsylvania Railroad sleeper car that carried them overnight from New York to Columbus, Ohio. In the morning passengers transferred onto a Ford Tri-Motor emblazoned with the TAT logo. They bounced from Indianapolis to St. Louis, Kansas City, Wichita, and, finally, Waynoka, Oklahoma. From there a Santa Fe locomotive steamed westward through the second night, bearing the travelers to Clovis, New Mexico by morning, where another Tri-Motor flew them by daylight to Albuquerque, Winslow (Arizona), and on to Los Angeles or even San Francisco.

For their substantial one-way fares of $338, passengers received their meals en route (featuring chicken salad in flight), comfortable transfers between train and plane, a lower berth on the sleeper car, and a colorful map that helped them trace their cross-country route. Colonel Lindbergh himself piloted one leg of the maiden flight, which counted his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh and fellow aviator Amelia Earhart among the dozen passengers (Fig 2).

Those making the initial flight received a handsome silk bookmark as a souvenir. It was made especially for the occasion by the E. H. Kluge Weaving Co. of New York City (Fig. 3). The Pennsylvania Railroad presented the travelers with a commemorative bronze paperweight (Figs. 4, 5).

TAT’s combined rail-air service crossed the country in about two days, a full day less than train travel alone required. Bi-coastal celebrities such as Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and Will Rogers took advantage of the luxury, speed and convenience. But continued reliance on the railroads for the trip’s night-time segments prompted some to quip that TAT stood for “Take a Train.”

A deadly encounter with Mount Taylor during a TAT flight over New Mexico in September 1929 killed everyone on board. Other serious accidents that followed in short order proved to be a fatal setback for the line, which was already losing money. Suspending the service in 1930, Keys folded TAT’s assets into other airline operations. The resulting consolidation would become known as TWA (initially Transcontinental & Western Air, eventually renamed Trans World Airlines).

Since the line was so short-lived TAT mementos are not common. But material occasionally does come to light. The rare presentation medal and bookmark shown in figures 3 and 4 recently turned up in two antique co-ops in New England and the Midwest. Print advertisements appear in magazines from the years 1929 and 1930 when the service was operating. Brochures, schedules, route maps and old tickets may yet linger in scrapbooks or unsorted attic boxes. TAT billheads, letters and documents must remain buried in business files.

Photographs of Ford Tri-Motors in TAT service as well as vintage toy TAT model planes occasionally appear in internet auctions. Also known are enameled lapel pins with the airline’s logo and “TAT Rail-Air” luggage tags. Collectors might encounter reproductions of some of these items. Avoid confusion with the European airline service, Transport Aerien Transregional, which adopted the “TAT” initials between 1969 and 1996.

Related posts: