Thomas Jefferson’s Books

By Maxine Carter-Lome

“I cannot live without books.” – Thomas Jefferson in a letter to John Adams, June 10, 1815

Throughout his life, reading and acquiring books were vital to Thomas Jefferson’s education and well-being. He relied on his books as his chief source of inspiration and practical knowledge, and believed that education was the means to an enlightened and informed citizenry that would help preserve democracy.

Jefferson was not only a voracious reader on all subjects but a life-long collector of books, amassing nearly 10,000 books over the course of his lifetime to build some of the country’s largest private libraries in America at that time.

The Shadwell Library

Jefferson first began collecting as a young man, amassing books on topics ranging from history and law to travel and religion. He stored these volumes in his family’s home, Shadwell. When Shadwell burned in 1770, Jefferson lost not only his library but the books he had inherited from his father, Peter Jefferson. Of the loss of his childhood home, it is said Jefferson mourned his books most of all.

The Monticello Library

Following the Shadwell fire, Jefferson wasted no time in replacing the library he lost. The destruction at Shadwell added impetus to his ambitious plans to start a new library for his new home, Monticello.

During his appointment as minister plenipotentiary and later minister to France from 1784 to 1789, Jefferson went on a buying spree, purchasing some 2,000 volumes while abroad for his library at Monticello. Before he returned to America in 1789, he compiled a separate list of the books he had acquired.

“While residing in Paris I devoted every afternoon I was disengaged, for a summer or two, in examining all the principal bookstores, turning over every book with my own hands, and putting by every thing which related to America, and indeed whatever was rare and valuable in every science. Besides this, I had standing orders, during the whole time I was in Europe, in it’s principal book-marts, particularly Amsterdam, Frankfort, Madrid, and London, for such works relating to America as could be found in Paris so that, in that department, particularly, such a collection was made as probably can never again be effected; because it is hardly probable that the same opportunities, the same time, industry, perseverance, and expense, with some knowledge of the bibliography of the subject will again happen to be in concurrence.”

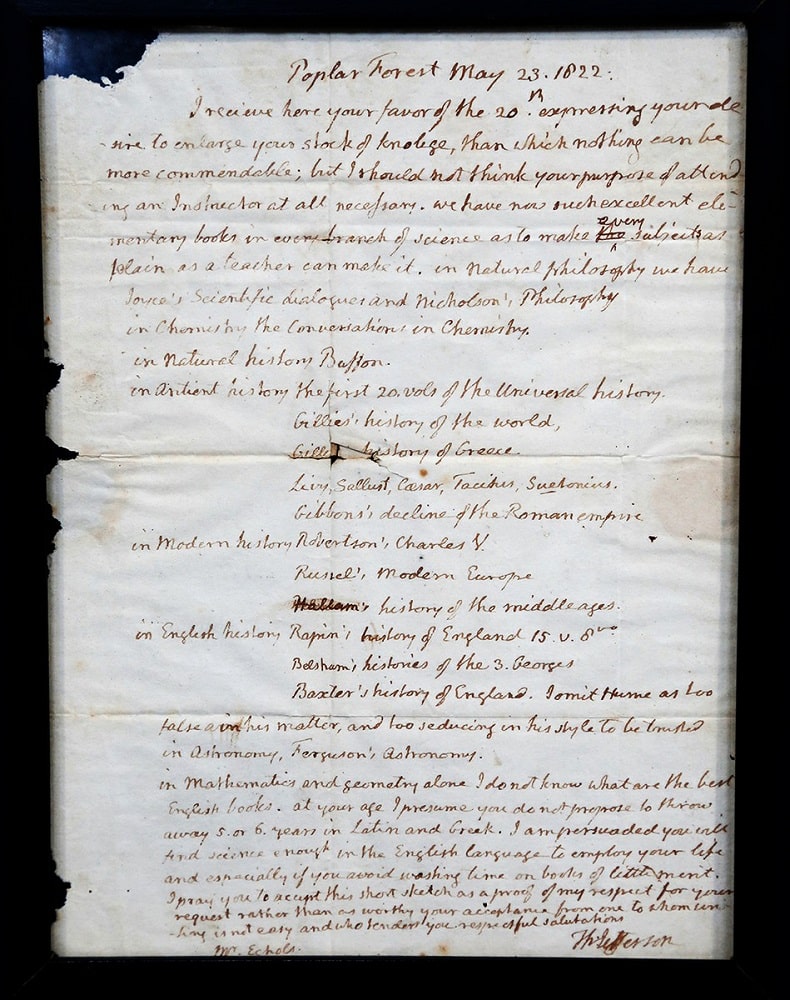

At its peak, Monticello had both a book room where Jefferson conducted his daily correspondence, architectural drafting, and recordkeeping, and a library that contained over 6,000 volumes classed according to subject and language. Most of the books in Monticello today represent the titles but not the original books that Jefferson owned.

Library of Congress

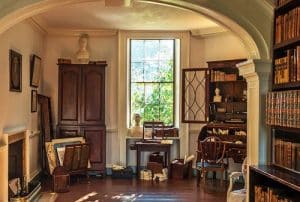

When the British burned down the U.S. Capitol in the War of 1812 they also destroyed the first Library of Congress and the 3,000-volumes inside. Jefferson had a close personal connection to the congressional library. During his tenure as president of the United States from 1801 to 1809, Jefferson had maintained a keen interest in the library and its development. Most notably, in 1802, he drew up a list of recommended books for Congress, which helped shape the library’s acquisitions at least until 1806.

Jefferson strongly felt that in order for Congress to govern effectively, it needed access to a working library of books and documents relating to all aspects of human knowledge. Congress was now without a library, and Jefferson was uniquely positioned to fill this need with his personal library at Monticello.

Although a second fire on Christmas Eve of 1851 destroyed nearly two thirds of the 6,487 volumes Congress had purchased from Jefferson, the Jefferson books remain the core from which the present collections of the Library of Congress—the world’s largest library—developed.

Retirement Library

After selling his books to Congress, Jefferson began collecting again. At the time of his death in 1826, his “Retirement Library” contained 940 items. He also maintained an over 600-volume library at his Poplar Forest retreat in Bedford County, which he started around 1811.

After his death in 1826, Jefferson’s remaining books were either disbursed to relations or sold at auction to pay the estate’s outstanding debts. Although historians have attempted to recreate Jefferson’s libraries using his hand-written catalog manuscripts as their guide, many of his books may never or only by chance be found, as was the case in 2011 when dozens of Thomas Jefferson’s books, some including handwritten notes from America’s third president, were found in the rare books collection at Washington University in St. Louis. The books were among about 3,000 that were donated to the school in 1880 after the death of Jefferson’s granddaughter, Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge, and her husband, Joseph Coolidge.

Sources:

- tjlibraries.monticello.org/

- loc.gov/exhibits/thomas-jeffersons-library/overview.html

- common-place.org/book/unquestionably-the-choicest-collection-of-books-in-the-u-s-the-1815-sale-of-thomas-jeffersons-library-to-the-nation/

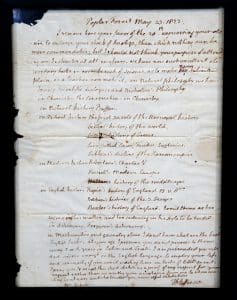

Jefferson’s response to a request from Joseph Echols – who was an orphan at just a year old and who had not received a proper education from his caregivers – for a list of books “that I may Receive the enjoyment of it myself but that I may be more useful to Society and more especially with a View to benefit my family.”

I receive here your favor of the 20th expressing your desire to enlarge your stock of knowledge, that which nothing can be more commendable; but I should not think your purpose of attending an Instructor at all necessary. We have now such excellent elementary books in every branch of science as to make ever subject as plain as a teacher can make it. In Natural philosophy, we have Joyce’s Scientific dialogues and Nicholson’s Philosophy in Chemistry The Conversation in Chemistry.

In Natural history Buffon.

In Ancient history the first 20 vols of the Universal history.

- Gillies’ history of the world,

- Gillies’ history of Greece,

- Livy, Sallust, Caesar, Tacitus, Suetonius.

- Gibbons’ Decline of the Roman Empire

In Modern history Robertson’s Charles V

- Russel’s Modern Europe

- Hallam’s history of the middle ages

In English history Rapin’s history of England

- Belsham’s histories of the 3 Georges

- Baxter’s history of England. I omit Hume as too false in his matter, and too seducing in his style to be trusted in Astronomy. Ferguson’s Astronomy.

In Mathematics and geometry alone I do not know what are the best English books. At your age I presume you do not propose to throw away 5 or 6 years in Latin and Greek. I am persuaded you will find science enough in the English language to employ your life and especially if you avoid washing time on books of little merit.I pray you to accept this short sketch as a proof of my respect for your request rather than as worthy your acceptance from one to whom writing is not easy and who tenders you respectful salutations,

WJefferson

Related posts: