Story & Photos by Donald-Brian Johnson

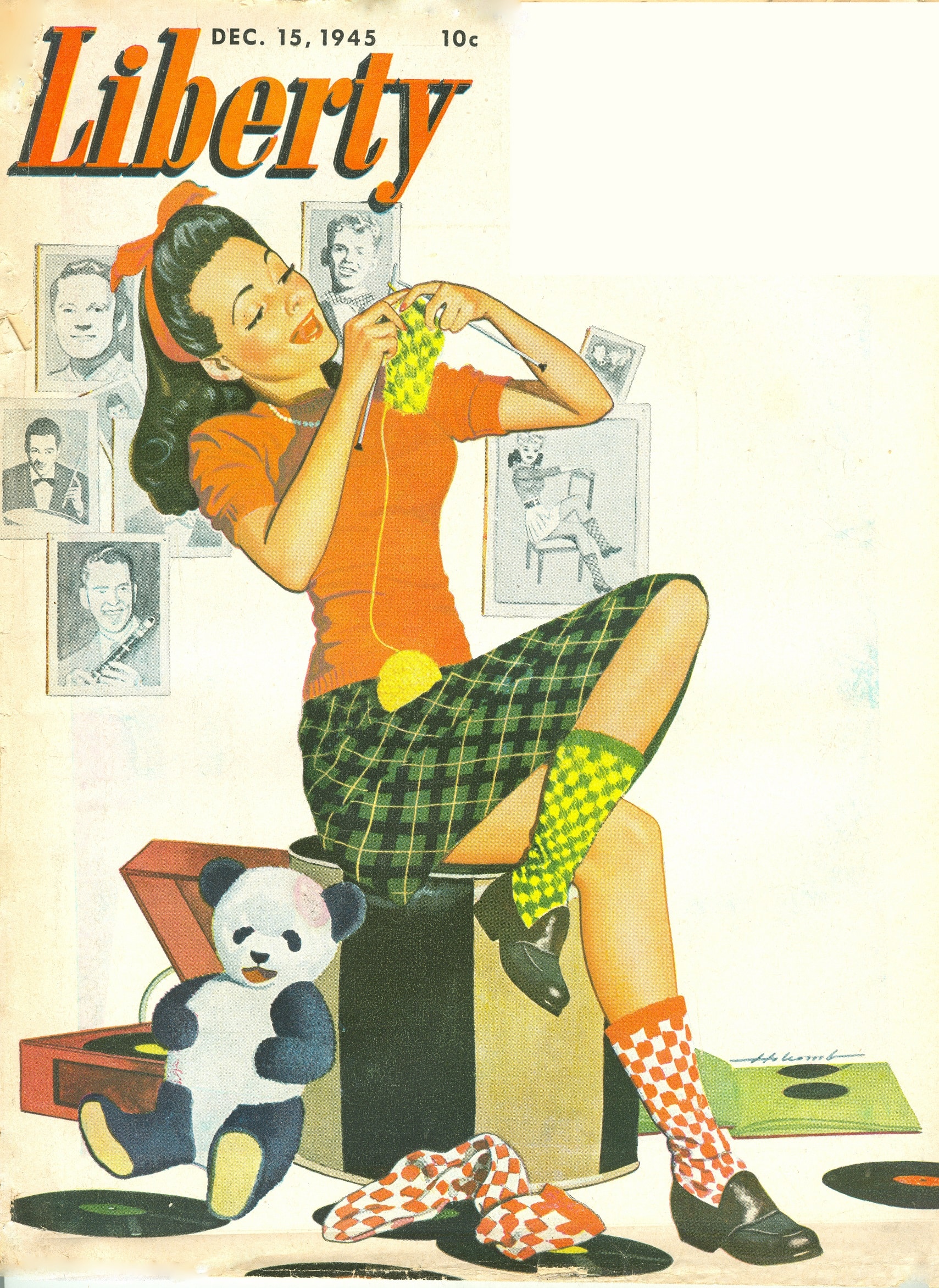

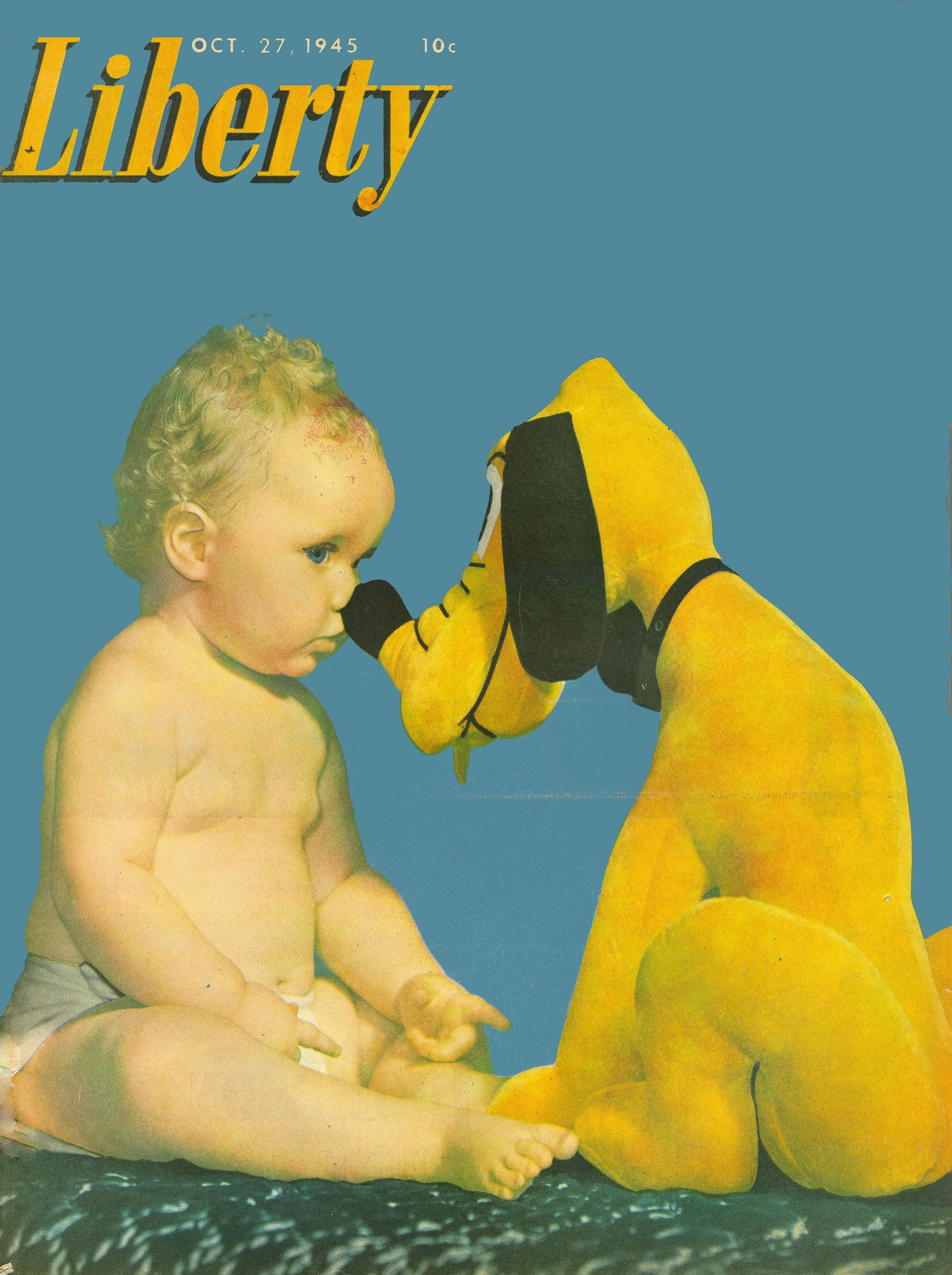

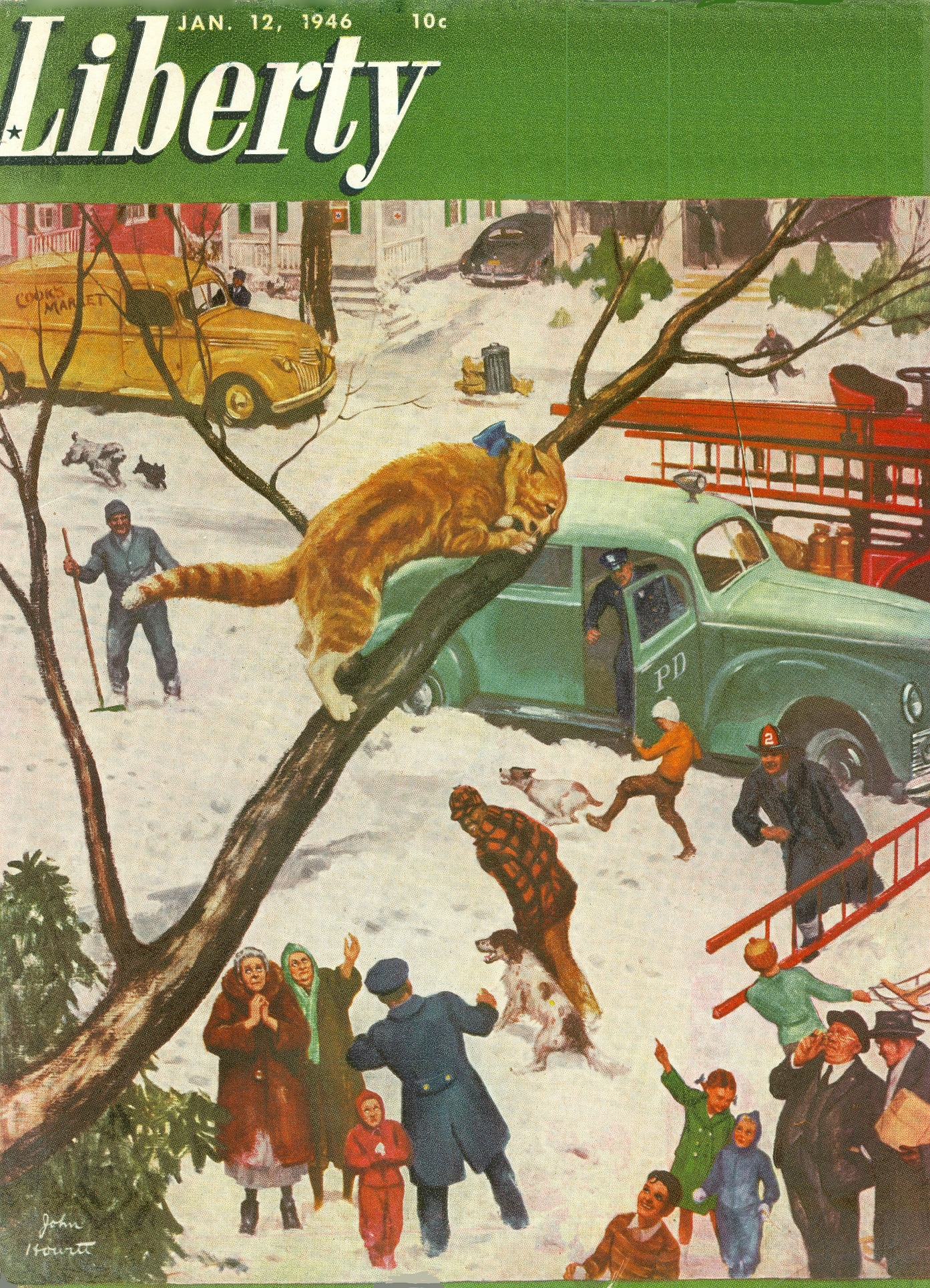

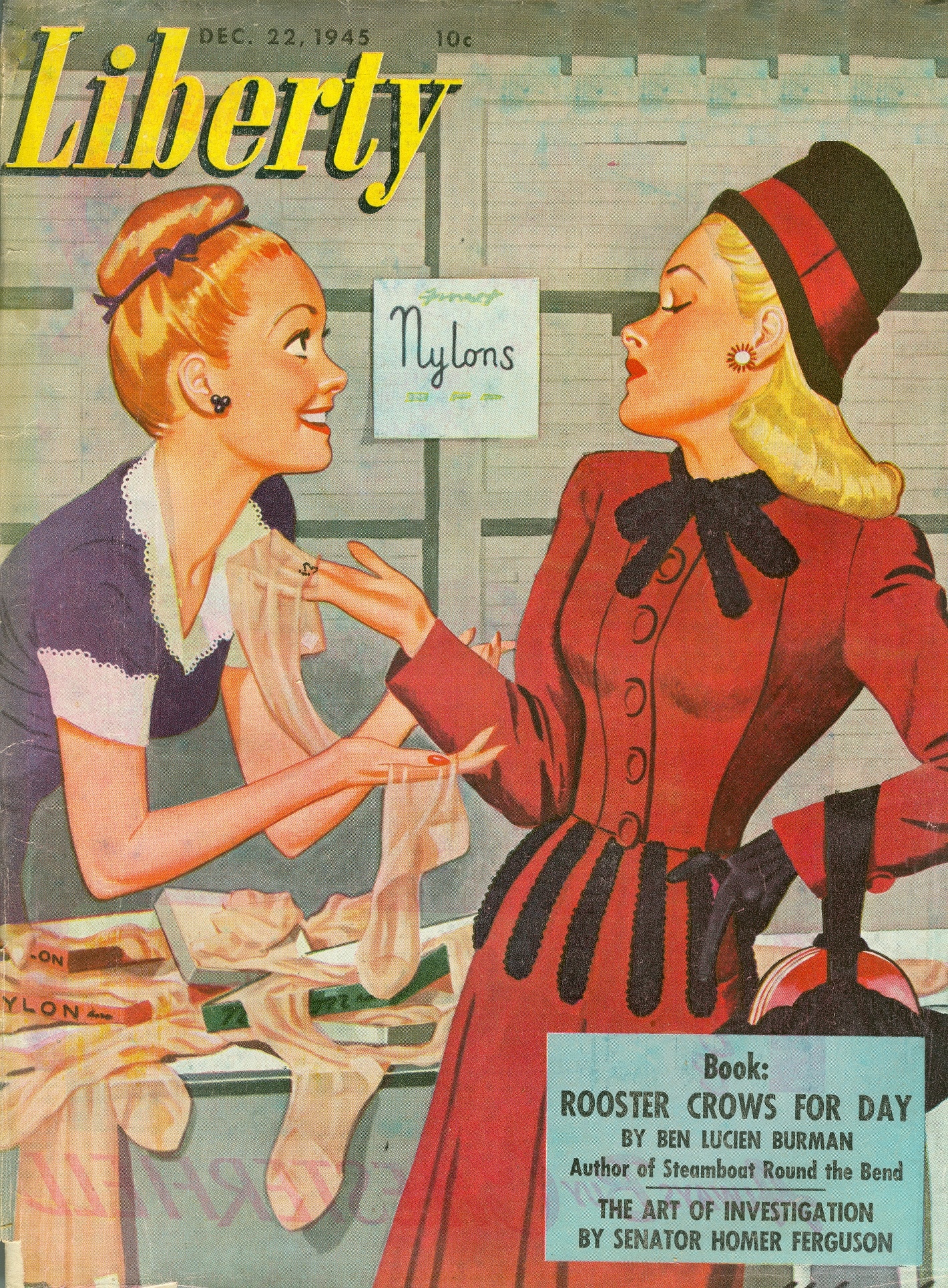

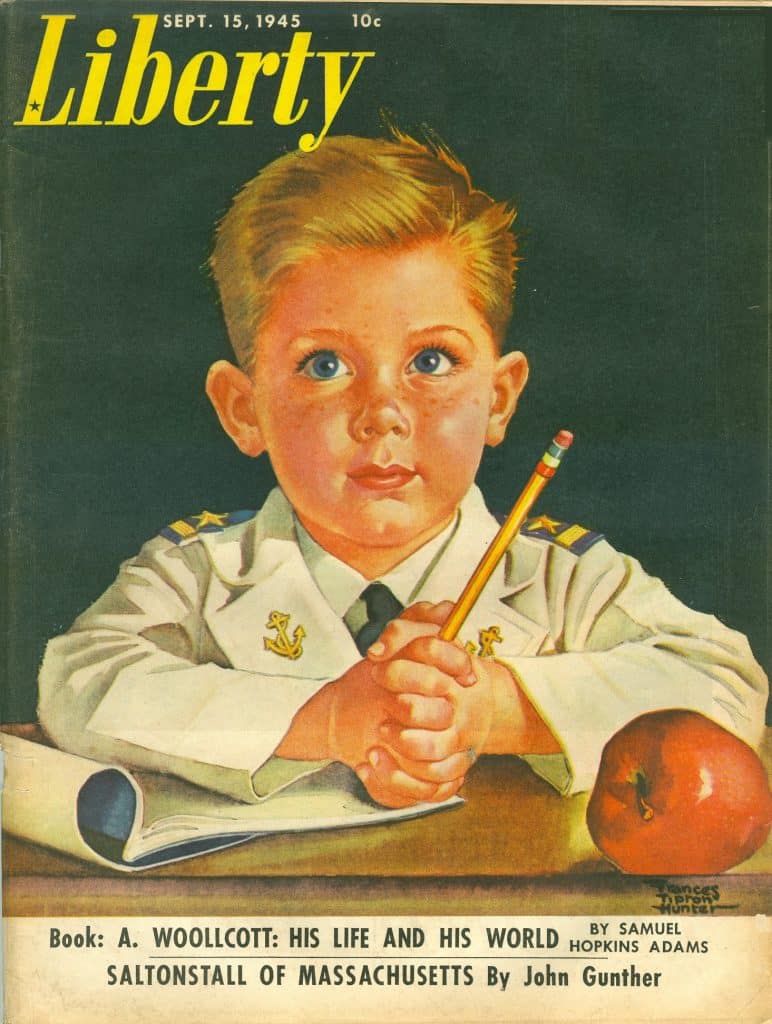

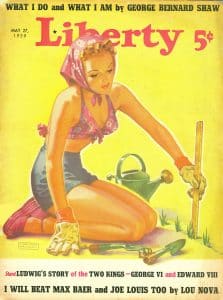

For thousands and thousands of mid-twentieth century Americans, the week just wasn’t complete without the latest issue of Liberty, the magazine that could be yours for just five cents. Even when the price later increased to a dime, Liberty was still a bargain.Here’s the sizzling lineup from just one issue: “Why I Will Not Marry” by Greta Garbo; “Did Stalin Poison Lenin?” by Leon Trotsky; “How Al Capone Would Run This Country”; “Jean Harlow: The Inside Story About My Husband’s Suicide”; “How To Dance The Big Apple” by Eleanor Powell; “My New Year’s Resolutions” by Shirley Temple.

Long before The National Enquirer or Keeping Up with the Kardashians, the spiciest showbiz stories came to brighten the day and lighten the load courtesy of Liberty.

New and Newsworthy

Liberty first hit the newsstands in 1924, a collaborative effort between two prominent publishers: cousins Captain Joseph Medill Patterson of the New York Daily News, and Colonel Robert Rutherford McCormick of the Chicago Tribune. American readers had long been held in thrall by another weekly, the Saturday Evening Post, but according to a pre-publication announcement, Liberty was geared toward a “more jazz-loving level of the public.” In other words, younger readers, presumably those who found the Post’s brand of grown-up folksiness too staid.

Patterson and McCormick had high hopes for their new venture, but that jazz-loving readership proved unreliable. Over seven years, Liberty lost twelve million dollars. Finally, in 1931, Liberty was sold to a publisher as colorful as its cover illustrations: the controversial Bernarr Macfadden.

Outspoken, eccentric, or just plain nuts? What folks thought of MacFadden was dependent on what they thought of his stridently expressed political and social opinions, which could change in a heartbeat. In 1932, for instance, Macfadden and Liberty stumped for the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt – nearly twenty articles trumpeted his talents. When FDR did make it to the White House, Macfadden quickly found the President’s policies unpalatable, and Liberty took an anti-Roosevelt tack. By 1936, the publisher was touting himself as a Republican presidential contender.

Talk of the Town

Regardless of Macfadden’s eccentricities, under his leadership, Liberty flourished. No longer courting young moderns, Liberty now celebrated, as it proudly proclaimed, “the American way of life” (at least as defined by Macfadden). Here’s a sampling of what readers had to look forward to in just one issue, dating from June 22, 1940:

- “Giving A Spanking” by Eleanor Roosevelt

- “Upstairs and Down in Hitler’s House”

- “Do Men Make Women’s Hats in Self-Defense?”

- Women Spies in Norway”

- Winston Churchill’s American Mother”

Also included: Princess Alexandra Kropotkin’s column, “To The Ladies’ (among her topics: Smart Styles for Tall Girls); and movie reviews by “Beverly Hills.”

Liberty’s ads are almost as much fun to read as the articles: Old Drum Blended Whiskey (“Suits your taste and suits your pocketbook”); Champion Spark Plugs (“ride high, wide, and handsome”); and Bromo-Seltzer (“it’s Gene Krupa’s way of ‘swinging away’ a headache”).

Heading things up was Macfadden’s opening editorial. The “Table of Contents” was relegated to Liberty’s last

Macfadden’s wasn’t the only voice blaring forth from the pages of Liberty. Each issue’s “Vox Pop” (voice of the people) featured letters from often volatile readers. A tongue-in-cheek political commentary by actor Frederic March elicited this response: “the irreverent––yes, blasphemous––way March dares to write angers any decent, right-thinking reader!”

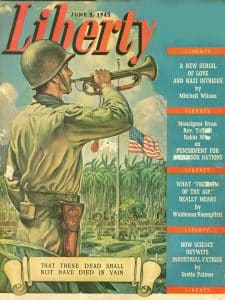

By the early 1940s, Macfadden was on his way out. Accusations of fund mismanagement and padded circulation numbers, coupled with a growing dislike for his prickly persona, led to a new, less politicized Liberty. During World War II and after, Liberty focused on the patriotic (“Purple Heart Junction: Honolulu’s Navy Hospital;” “This Man’s Army” by “Old Sarge”), the lighthearted (“The Care and Feeding of Husbands” by Gracie Allen), and that old stalwart, Hollywood: up-close, personal, and usually ghost-written (“Houses I Have Haunted” by Boris Karloff.)

Only in Liberty

Among the most fondly remembered Liberty idiosyncrasies was the reading time that appeared at the beginning of each story. A Liberty staffer would time himself reading the article. Taking into account less skilled readers, that time was doubled, the estimate appearing below the article’s byline. You could whisk your way through a review of Citizen Kane in just 4 minutes and 40 seconds, or take a more leisurely mental stroll for “The Experiences of a Broadway Star in Jail” by Mae West (14 minutes). Not counting untimed features––crossword puzzles and ads––totting up the time estimates meant that, if you put your mind to it, you could get through an entire issue of Liberty in just about 3 uninterrupted hours. (Incidentally, the reading time for the article you’re reading right now is an estimated 12 minutes and 28 seconds. I checked.)

Equally well-remembered were the “Liberty Boys” who hawked the magazines door-to-door and at newsstands (there were also plenty of uncredited “Liberty Girls”). Saleskids earned Brownie Coupons to redeem for “high-grade baseball goods, football goods, bicycles, radio sets, jewelry, and musical instruments.” The publication Liberty Boy Salesman recognized the efforts of these young entrepreneurs, especially members of the “Thousand Club” – those selling more than a thousand copies of Liberty each week!

Related posts: