By Erica Lome

The year 1916 marked the final issue of Gustav Stickley’s influential periodical The Craftsman, which introduced American audiences to the British-derived Arts and Crafts movement. Nearly a hundred years later, many of Stickley’s distinct products – ranging from furniture and lighting to carpets and textiles – continue to appeal to collectors. Yet few realize just how ahead of his time Stickley was, advocating a holistic approach to design which encompassed landscape, architecture, and interior furnishings. With his socially-minded artistic agenda, we might even consider him a precursor to the lifestyle and branding gurus popular today. With many of his products now considered among fine antiques, 2016 marks a centennial of sorts for Stickley, and begins a new chapter for fans of his works. A visit to The Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms in Morris Plains, New Jersey allows us to reconsider the legacy and ideals of a master craftsman.

Gustav Stickley was born in 1858 in Osceola, Wisconsin to German immigrant parents. He was trained and employed as a stonemason before moving with his family to Pennsylvania where he learned the furniture trade at his uncle’s chair factory, later opening the Stickley Brothers Company in 1883 with two of his four brothers. A trip to Europe in 1896 opened his eyes to the Arts and Crafts movement, already prominent in Britain due to the pioneering efforts of designers and tastemakers William Morris and John Ruskin. Inspired, Stickley returned to America and established the furniture business that became his renowned Craftsman Workshops of Syracuse, New York. By 1900, after a successful debut of his furniture line at the Grand Rapids show, Stickley’s pared-down aesthetic soon caught on with customers sick of over-ornamented and lifeless Victorian objects. A Gustav Stickley piece reflected simplicity, craftsmanship, and naturalism. Working to “batch” produce his products with a mix of modern machinery and handworking skill, Stickley and his men aestheticized the means of construction: colorants applied to highlight the grain of the wood, solidity emphasized by visible joinery, and careful, detailed inlay as decoration.

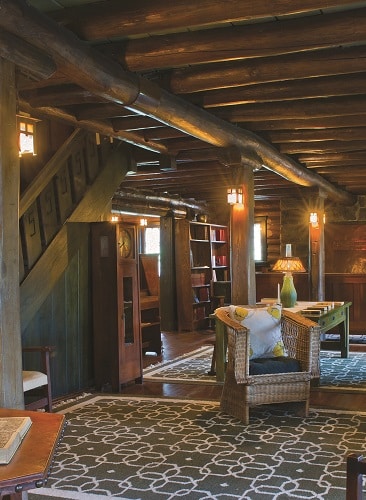

As his “country estate,” the 650 acres and twelve buildings at Craftsman Farms, became his design laboratory. The family home, known as the Log House, was the only home designed and built by Stickley for his own use. Whereas his Syracuse factory supplied his product, Craftsman Farms served as a model for what middle class Americans might aspire to. Stickley’s ideology for design was akin to one of his possible influences, Frank Lloyd Wright. Whereas Wright began with houses and later designed furniture to compliment the architecture, Stickley approached it from the other side – designing his products with the aim of creating a total aesthetic experience to orient his customers toward demanding better quality in every aspect of their lives. With his business, a client could design, build, and furnish their home all through The Craftsman Workshops: one-stop shopping in its earliest incarnation.

Stickley became a model for the aesthetic lifestyle he advocated, designing furniture and architecture that he himself lived with. The original plans for Craftsman Farms reflect his dream of creating a community of self-sufficient makers, with housing to fit approximately twenty families, a private school, orchards, a vineyard and a dairy. Unfortunately, Stickley’s broader plans never came to fruition: as World War I approached, so did American taste begin to turn away from the Craftsman aesthetic. His factory in Syracuse attempted to keep up with changing trends by producing different styles of furniture, including his painted colonial revival-inspired “Chromewald” line and the typical bedroom sets to be catalogue-ordered. As a recession began in1913, Stickley opened a twelve-story department store in the eponymously named Craftsman Building in New York City, forcing the company into financial instability. Stickley fought tirelessly to keep his business and dream of Craftsman Farms afloat – these aims proved to be incompatible and ultimately disastrous. In 1915 the company declared bankruptcy. Soon after, The Craftsman folded, ending its much-lauded and influential run.

Today, Stickley remains a household name in the design world, thanks in part to a revived scholarly interest in the American Arts and Crafts movement and an avid collectors’ market for his products. The Audi family, current owners of Stickley Audi & Co. (formerly the L. & J.G. Stickley Company), offer reissues of Gustav Stickley furniture today, and recent museum exhibitions have re-introduced Gustav and the Craftsman style to new generations. In addition, Craftsman Farms is open to visitors as the Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms, a designated National Historic Landmark, and named a Distinctive Destination by The National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The Stickley Museum retains nine of the original twelve farm buildings on thirty acres of parkland, which includes the Stickley’s family home, the Log House, re-appointed with most of its original furnishings and curated to re-imagine how the family lived during their tenure at the residences. One of the bedrooms occupied by Stickley’s four daughters looks as lively and artfully cluttered as if they still slept there today. Its modern open floorplans and earthy palette underscore the natural beauty of its environs. Walking through the space imbues a palpable feeling of wonder for the potential of hand-crafted design to be a restorative balm to the soul. It seems that Gustav Stickley’s ideals remain as true today as they did one hundred years ago.

The Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms is open year-round, offering sixteen scheduled tours weekly, with special interest and group tours available by appointment. Museum hours are Thursday through Sunday, 12-4pm. Tours begin hourly at 12:15, 1:15, 2:15 and 3:15. Admission is $10 for adults, $7 for seniors and students, $4 for children up to age 12. For more information, please visit the museum website (www.stickleymuseum.org) or call 973-540-0311.

Erica P. Lome holds an MA in Design History from the Bard Graduate Center, and is currently a doctoral student at the University of Delaware in the History of American Civilization Program. She is also the Editorial Assistant for Winterthur Portfolio and is the Academic Programs Assistant at Winterthur Estate, Museum & Library.

-

- Assign a menu in Theme Options > Menus WooCommerce not Found

Related posts: