American Fashion and Tailoring as made by The John J. Mitchell Publishing Company

by Judy Gonyeau, managing editor,

with information shared by Jean Druesdow, director emerita, Kent State University Museum

A gentleman never talks about his tailor.

– Nick Cave, artist, and creater of “Soundsuits”

That may be true, but a good tailor, one who knows his stuff and presents the latest in fashion, is someone that was treasured by the American Gentleman of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Tailors to the upper echelon of society needed to have the education and tools at hand so every stitch, fabric choice, fit, and overall style was perfectly executed.

Enter the John J. Mitchell Company of New York City.

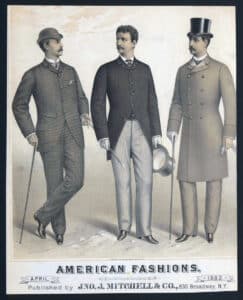

Established in the mid-19th century, the Mitchell Company was strident in its efforts to stand above and apart from other businesses looking to lead the way of American fashion. They provided education and shared their vast amount of tailoring expertise to those working in the field using a host of marketing tools: publishing magazines, establishing a world-renowned cutting and tailoring school, creating advertising and finely printed illustrations tailors would display in their shops, and being a supportive presence at tailor organizations’ meetings, conventions, supporting Union efforts, and placing American Fashion on the world stage.

The Unknown Trend-Setter

So, why haven’t we heard about the Mitchell Company? Most likely because this company was perceived as a “behind-the-seams” type of trade business. It could also be a lack of documentation on the business, itself. Reference material on how the business was run, statistics on the volume of magazines, or even who John J. Mitchell was is tough to find. Only recently has the Met Museum obtained a collection of Mitchell ephemera as part of a bequest from Edward W. C. Arnold. The ephemeral nature of the Mitchell Company does not appear to be well preserved. Somewhere there could be a huge treasure trove waiting to be discovered.

According to Jean Druesdow, director emerita, Kent State University Museum, and author of Men’s Fashion Illustrations from the Turn of the Century published by Dover (1990), “I do understand how difficult it is to track down any information about the J.J. Mitchell Publishing Company. I was interested primarily in the plates and patterns they published, and in the commentary – how the button spacing changed 1/4” and that was NEWS.”

Digging through information from the remaining existing examples of the many prints, publications, and books by Mitchell Publishing helped to build its story.

Fashion Publishing

Historian Frank Luther Mott (1886-1964) took note of the volume of Mitchell fashion publications by sharing how they started and how they changed over time to focus on American trends. Keeping up with this was not an easy task, as you will see.

According to Mott, the Jno. J. Mitchell Publishing Company started out with The Clothier and Hatter in 1872, later divided into two publications: Clothier and Furnisher and Hatter and Furrier. Then, in 1892, it all switched once again. Hatter and Furrier split and became American Hatter and the Furrier (later Fur Trade Review).

Another morphing magazine was The Furnishing Gazette, founded in 1881, that also switched its title to The Haberdasher from 1887 to 1931.

The star publication that reached across all aspects of the tailoring trade was the long-running Sartorial Art Journal, established in 1874. First titled The American Fashion Review, the name change in 1887 stayed with the publication until its last issue in 1954.

And perhaps the most influential publication next to The Sartorial Art Journal was American Tailor and Cutter (1880-1916). The two magazines appear to be the foundation of much of the information dispensed to those in the tailoring community that spoke to them about the broader scope of the industry.

The Sartorial Art Journal

At its beginnings, this long-running trade journal served the Merchant Tailors’ National Protective Association specifically, and the tailoring and fashion design trade in general. The Journal marketed Mitchell’s tools of the trade, such as patented measuring devices, patterns, and fashion plates.

Over time, this once pamphlet-sized publication expanded to over 100 pages per issue by adding business news, tips, instructions on tailoring techniques, business advice, union activity, international news, and more examples of current fashions.

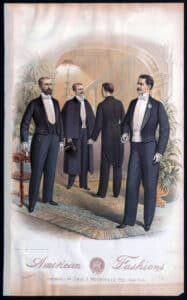

The Journal came in two versions—one for men and the other for women—and included full-page, detailed illustrations showing the upcoming season’s fashion looks. Along with the larger prints were smaller, color versions printed separately and inserted into the magazine. These smaller cards were intended to be used by tailors to show his clients what was possible – and kept the Mitchell name front and center. They included a subtle use of color to set the tone.

According to Druesdow, “Admittedly, color doesn’t add a whole lot to the depictions of evening wear but it certainly brings the backgrounds to life. Backdrops were often based on real New York locations such as Grant’s Tomb and the now-demolished Vanderbilt houses and the old Waldorf-Astoria hotel. Furthermore, the extremely high resolution is astounding in its ability to allow up-close inspection of the smallest details.”

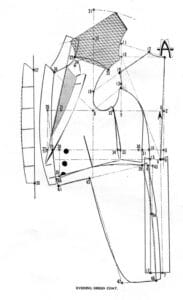

Other prints and cards included in the Journal were illustrations of images of Mitchell’s cutting techniques. These were lauded for their detail and forward-thinking design. Some of these are still studied by costume and fashion students today.

When speaking about the detailed illustrations and how they came to be, Druesdow notes that in April 1905, the editors proclaimed: “… everything we illustrate is first sketched from the thing itself and that the thing itself is the product of some high-class metropolitan tailoring establishment that had kindly loaned it to us for that special purpose; the novelties we illustrate are not experiments but new things that men of high reputation are wearing …”

The editors then went on to mention illustrating the “daring tastes of tailors of high standing” who dress “acknowledged leaders in exclusive social circles.” Over time, these images provided a strong visual history of American men’s fashions as determined by this early influencer.

A Marriage Tailor Made by Mitchell

The Mitchell Company opened its first school for tailors at its publishing company in New York. Once Mitchell created its “Standard” pattern-making system for creating patterns, having a school in which to teach it was a logical next step.

American Tailor and Cutter was the clear focus of Mitchell’s marketing efforts to entice potential students to sign up for the course.

A large number of advertisements were placed in Mitchell’s other publications, as well. Within its pages, both American Tailor and Cutter and The Sartorial Journal shared illustrations showing the newly named “Mitchell Standard System of Cutting” as part of its overall marketing program.

The introductory name of the school proved to be a mouthful – The Jno, J. Mitchell Co. School of Garment Cutting, Tailors’ Implements, Publishers of American Fashions, Works on Cutting.

The brick-and-mortar school married with Mitchell publications helped establish the Mitchell School as the most successful of its kind.

As a sidebar, Mitchell’s American Tailor and Cutter, which ran from 1880 to 1916, published almost the entire set of Standard cutting methods (there was one Standard for just about every piece of clothing and haberdashery made). This pivotal element used for garment construction (the paper pattern) was associated with many future pattern makers becoming successful – even the everyday seamstress.

Attend Our School

To entice readers of American Tailor and Cutter to enter the School, Mitchell would publish something akin to an “advertorial,” or a story that was heavily edited and probably embellished by the magazine’s editors. In this example from the March 1902 issue, Arthur Scherrer of St. Gall, Switzerland shared the positively bubbly correspondence he mailed to his family as he was heading home after attending the New York school. This paints a picture of a large business with state-of-the-art facilities and just happens to play up the many high points about the capabilities of not just the school, but the company as a whole.

“One floor is entirely occupied by the Mitchell establishment with its various departments. There is the art department where the fashion plates are designed – you know how much we and our tailors admired them. They are equaled nowhere, and I have seen many of them everywhere where good tailors were to be found. The printing of The Sartorial Art Journal, Men’s and Ladies’ Tailor editions—the first in four different languages: English, French, Spanish, and German, of the American Tailor and Cutter and of textbooks, etc.—together with the etching, engraving and the like, are all done in other buildings. There isn’t space in this building for them.

“Then there is the cutting school, which is divided into three departments, each under competent instructors. There are two for men’s systems and the other is for ladies’ tailoring. One of the men’s systems is called the Madison, and the other is the Standard. One is a long measure and the one I named last a short measure system. I do not think it makes any difference which one is studied, both are the best known and both give excellent results.

“… With each man in the establishment a well-paid specialist, and with everything at his command that mechanical ingenuity can supply to facilitate business—and this is typically American—can you wonder that the Mitchell fashions, etc., and the products of the United States are obtaining such a hold in Europe and elsewhere?”

These and other examples dropping not-so-hidden hints to would-be students and locations, alike, are scattered time and time again across any and every item published by Mitchell.

Ah, Paris, as told to Mitchell by The Tailor

Perhaps one of the most interesting self-proclamations made by Mitchell was in the August 1901 pages of The Sartorial Art Journal.

The “story” of a gentleman attending the 1889 Paris Exposition.

This unnamed source (“The Tailor”) expounded upon the many Jno. J. Mitchell Publishers prints that were given out to visitors at the Merchant Tailors of New York display. The Tailor seemed to infer these publications and printed cards, along with a free one-day course of instruction in tailoring given on Mitchell Standard techniques, led to awards being given to the Merchant Tailors of New York for their overall presentation.

The exhibit featured 21 garments contributed by many of the best tailors from larger cities in the U.S. A painting formed the background with mirrors placed so viewers could see the garments from all sides. “That the United States should make such an exhibit in Paris did not seem so extraordinary after the installation was seen.” While research into the specifics of who actually contributed what would require a greater amount of investigation, the hand of the Mitchell company as an influencer is not out of the question.

There was, indeed, an award given. According to the Report of the Commissioner-general at the Exhibition, “The exhibit of the Merchant Tailors’ National Exchange of the United States of America was granted a gold medal, which was the highest award given to tailoring work.”

Among the other claims from The Tailor shared in the August 1901 issue of American Tailor and Cutter:

“The sartorial supremacy of the world has ceased to be a disputable question. There are two unmistakable proofs that it belongs to this country. These are the award of the gold medal to the Merchant Tailors’ National Exchange, by the recent Paris Exposition, for the superiority over all others of the garments the exchange exhibited at the exposition, and the publications, standing, influence, and work of The John J. Mitchell Co., of New York.

“… To the John J. Mitchell Co., the sartorial world is indebted for the finest illustrations of fashions it has ever known: for the most logical, comprehensive, and practical period expositions of the ethics of dress, and last, but not least, as it is fundamental, for the unmatched excellence of the technical art instruction its School of Cutting diffuses through all tailordom.”

Kind words from The Tailor, indeed!

Final Stitches

Without any set reference materials on the Mitchell Companies to present a clear story, there are bits and pieces of its story scattered within the stories of surviving publications and books that caught the eye of this writer. Here are just a few.

• In advertisements in its publications, the Mitchell School of Garment Cutting recommended the “dull season after the holidays” as the best time to enroll in one of their courses.

• Making it easier for students to attend its school, Mitchell helped its students with everything from securing lodging to buying scissors and the like.

• The Cutting course was taught using what we consider today “independent study.” The student could start the course at any time and an experienced tailor working in the trade would teach the student 1:1 at a pace suited to the student. There were limits regarding the total number of weeks a student could attend to complete the course.

• While attending the school, there were also opportunities for students to tour the Mitchell facilities, network with others in the business, and even secure employment upon completing their studies, often within the Mitchell organization as it would cherry-pick the best of its graduates to work as a tailor and sometimes as an instructor.

• For the turn-of-the-century tailor, another marketing tool offered for purchase was the “Mitchell Postcards for Advertising or Business Correspondence.” These cards featured room for addressing them to your clientele, space for a personalized note, and a drawing of the very latest offerings from the business. For just $5, the business would receive 500 postcards ready to be filled in and sent out – or pay just $7.50 for 1,000. They were “Made in 12 styles, including sacks, cutaways, frocks, overcoats, Norfolks, dress suits, etc. Sold separately or assorted. … Just the thing for sending out notices of try-on, etc.” Who could resist?

• Books published by Mitchell included The New Standard Coat System, Works on Cutting, New Standard Trousers and Breeches Systems, Work on Designing and Pattern-Making of Ladies’ Tailor-Made Garments, and the New Standard Coat and Vest Systems. Regarding the “New Standard,” the Company stated that “It is thoroughly and radically new.”

• When speaking to how to tailor men’s riding breeches, the Mitchell System stated that “the reason that the openness, or leg spread, is not increased for large men, and decreased for small ones, is that for both the spread is adapted to the diameter of the body of the horse from side to side, not to the natural spread of the wearer’s legs.” Imagine how many pairs of breeches were tailor-made for the rider with a full barn.

Thanks to the many opportunities given to support the tailors of the 19th and early 20th centuries, they were able to become successful purveyors of services to American Gentlemen with clothing to represent their class, influence, and personal style – as directed by the Jno. J. Mitchell Companies.