Page 24 - joa 2-2020

P. 24

“ Wher the oven bakes & the pot biles”

POTTERY OF

SOUTH CAROLINA’S

EDGEFIELD DISTRICT

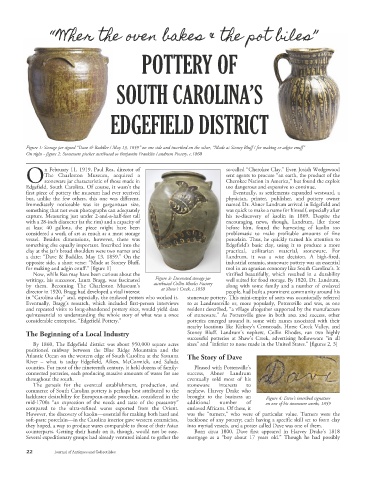

Figure 1: Storage jar signed “Dave & Baddler / May 13, 1859” on one side and inscribed on the other, “Made at Stoney Bluff / for making or adgin enuff”

On right - figure 2: Stoneware pitcher attributed to Benjamin Franklin Landrum Pottery, c.1860

n February 11, 1919, Paul Rea, director of so-called “Cherokee Clay.” Even Josiah Wedgewood

The Charleston Museum, acquired a sent agents to procure “an earth, the product of the

Ostoneware jar characteristic of those made in Cherokee Nation in America,” but found the exploit

Edgefield, South Carolina. Of course, it wasn’t the too dangerous and expensive to continue.

first piece of pottery the museum had ever received Eventually, as settlements expanded westward, a

but, unlike the few others, this one was different. physician, printer, publisher, and pottery owner

Immediately noticeable was its gargantuan size, named Dr. Abner Landrum arrived in Edgefield and

something that not even photographs can adequately was quick to make a name for himself, especially after

capture. Measuring just under 2-and-a-half-feet tall his re-discovery of kaolin in 1809. Despite the

with a 28-inch diameter (at the rim) and a capacity of encouraging news, though, Landrum, like those

at least 40 gallons, the piece might have been before him, found the harvesting of kaolin too

considered a work of art as much as a meat storage problematic to make profitable amounts of fine

vessel. Besides dimensions, however, there was porcelain. Thus, he quickly turned his attention to

something else equally important. Inscribed into the Edgefield’s basic clay, using it to produce a more

clay at the jar’s broad shoulders were two names and practical, utilitarian material, stoneware. For

a date: “Dave & Baddler, May 13, 1859.” On the Landrum, it was a wise decision. A high-fired,

opposite side, a short verse: “Made at Stoney Bluff, industrial ceramic, stoneware pottery was an essential

for making and adgin enuff.” [figure 1] tool in an agrarian economy like South Carolina’s. It

Now, while Rea may have been curious about the vitrified beautifully, which resulted in a durability

writings, his successor, Laura Bragg, was fascinated Figure 3: Decorated storage jar well suited for food storage. By 1820, Dr. Landrum,

by them. Becoming The Charleston Museum’s attributed Collin Rhodes Factory along with some family and a number of enslaved

director in 1920, Bragg had developed a vital interest at Shaw’s Creek, c.1850 people, had built a prominent community around his

in “Carolina clay” and, especially, the enslaved potters who worked it. stoneware pottery. This mini-empire of sorts was occasionally referred

Eventually, Bragg’s research, which included first-person interviews to as Landrumville or, more popularly, Pottersville and was, as one

and repeated visits to long-abandoned pottery sites, would yield data resident described, “a village altogether supported by the manufacture

quintessential to understanding the whole story of what was a once of stoneware.” As Pottersville grew in both area and success, other

considerable enterprise, “Edgefield Pottery.” potteries emerged around it, some with names associated with their

nearby locations like Kirksey’s Crossroads, Horse Creek Valley, and

The Beginning of a Local Industry Stoney Bluff. Landrum’s nephew, Collin Rhodes, ran two highly

successful potteries at Shaw’s Creek, advertising hollowware “in all

By 1860, The Edgefield district was about 950,000 square acres sizes” and “inferior to none made in the United States.” [figures 2, 3]

positioned midway between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the

Atlantic Ocean on the western edge of South Carolina at the Savanna The Story of Dave

River – what is today Edgefield, Aiken, McCormick, and Saluda

counties. For most of the nineteenth century, it held dozens of family- Pleased with Pottersville’s

connected potteries, each producing massive amounts of wares for use success, Abner Landrum

throughout the south. eventually sold most of his

The genesis for the eventual establishment, production, and stoneware interests to

commerce of South Carolina pottery is perhaps best attributed to the nephew, Harvey Drake who

lackluster desirability for European-made porcelain, considered in the brought to the business an Figure 4: Dave’s inscribed signature

mid-1700s “an expression of the needs and taste of the peasantry” additional number of on one of his stoneware works, 1859

compared to the ultra-refined wares exported from the Orient. enslaved Africans. Of these, it

However, the discovery of kaolin—essential for making both hard and was the “turners,” who were of particular value. Turners were the

soft-paste porcelain—in the Carolina interior gave western ceramicists, backbone of any pottery; each having a specific skill set to form clay

they hoped, a way to produce wares comparable to those of their Asian into myriad vessels, and a potter called Dave was one of them.

counterparts. Getting their hands on it, though, would not be easy. Born circa 1800, Dave first appeared in Harvey Drake’s 1818

Several expeditionary groups had already ventured inland to gather the mortgage as a “boy about 17 years old.” Though he had possibly

22 Journal of Antiques and Collectibles