Page 29 - JOA-2-22

P. 29

specialized trade, reveals approximately 269 active makers in the United rediscovering Cesar Chelor’s planes already in their collections and

States. 69 of those were from Massachusetts, following a path Cesar are working with scholars to elucidate the details of his life and the lives

Chelor helped make possible and profitable. of other Black craftspeople in early America. These worthy efforts

Chelor also charted a course followed by other Black planemakers in prove that even the humblest of objects can transform our understanding

the early nineteenth century, such as John A. King and John Teasman, of history.

who worked in Newark, New Jersey between 1835 and 1837. In New

York City, George Bale was active between 1842 and 1860. Women Erica Lome, Ph.D., is currently the Peggy N. Gerry Curatorial Associate at the

Concord Museum, sponsored by the Decorative Arts Trust. She holds a doctorate in

also supervised the manufacture of wooden planes. Charlotte White of history from the University of Delaware and a MA in decorative arts, design history,

Philadelphia was active in 1840 and Catherine Seybold of Cincinnati and material culture from the Bard Graduate Center.

was active between 1853-55; both

took over the businesses of their

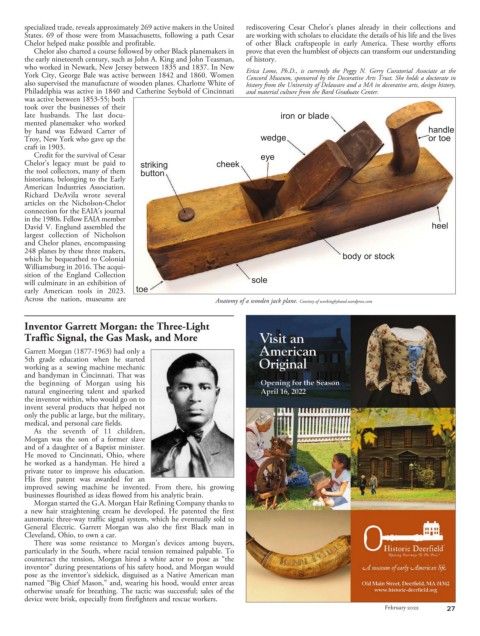

late husbands. The last docu- iron or blade

mented planemaker who worked

by hand was Edward Carter of handle

Troy, New York who gave up the wedge or toe

craft in 1903.

Credit for the survival of Cesar eye

Chelor’s legacy must be paid to striking cheek

the tool collectors, many of them button

historians, belonging to the Early

American Industries Association.

Richard DeAvila wrote several

articles on the Nicholson-Chelor

connection for the EAIA’s journal

in the 1980s. Fellow EAIA member

David V. Englund assembled the heel

largest collection of Nicholson

and Chelor planes, encompassing

248 planes by these three makers,

which he bequeathed to Colonial body or stock

Williamsburg in 2016. The acqui-

sition of the England Collection

will culminate in an exhibition of sole

early American tools in 2023. toe

Across the nation, museums are Anatomy of a wooden jack plane. Courtesy of workingbyhand.wordpress.com

Inventor Garrett Morgan: the Three-Light

Traffic Signal, the Gas Mask, and More

Garrett Morgan (1877-1963) had only a

5th grade education when he started

working as a sewing machine mechanic

and handyman in Cincinnati. That was

the beginning of Morgan using his

natural engineering talent and sparked

the inventor within, who would go on to

invent several products that helped not

only the public at large, but the military,

medical, and personal care fields.

As the seventh of 11 children,

Morgan was the son of a former slave

and of a daughter of a Baptist minister.

He moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where

he worked as a handyman. He hired a

private tutor to improve his education.

His first patent was awarded for an

improved sewing machine he invented. From there, his growing

businesses flourished as ideas flowed from his analytic brain.

Morgan started the G.A. Morgan Hair Refining Company thanks to

a new hair straightening cream he developed. He patented the first

automatic three-way traffic signal system, which he eventually sold to

General Electric. Garrett Morgan was also the first Black man in

Cleveland, Ohio, to own a car.

There was some resistance to Morgan’s devices among buyers,

particularly in the South, where racial tension remained palpable. To

counteract the tension, Morgan hired a white actor to pose as “the

inventor” during presentations of his safety hood, and Morgan would

pose as the inventor’s sidekick, disguised as a Native American man

named “Big Chief Mason,” and, wearing his hood, would enter areas

otherwise unsafe for breathing. The tactic was successful; sales of the

device were brisk, especially from firefighters and rescue workers.

February 2022 27