Page 30 - joa-6-23

P. 30

styles from the seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries. Efforts

were made to create rooms that were “of the period.”

Writing to interior designer Henry Davis Sleeper in 1930, du Pont

stressed that at Winterthur he was “doing the house archaeologically

and correctly, and am paying the greatest attention even to the epoch

of fringes.” When creating window treatments, du Pont did indeed

refer to design books of the appropriate period as well as surviving

examples of historic valances. These, however, he would adapt to suit

the project at hand. At the end of the day, for du Pont, aesthetics always

trumped historic accuracy. In his own office, for example, he preferred

an 1830s chintz for curtains although the room was created with archi-

tectural paneling from a 1790 addition to a house built in 1760. The

dates didn’t fit, but the mix looked “right.” In effect, du Pont was

creating beautiful installations that featured his extraordinary collection.

The English paste-printed cotton (1770) in the Hampton Room

features exotic flowers and undulating vines that complement the

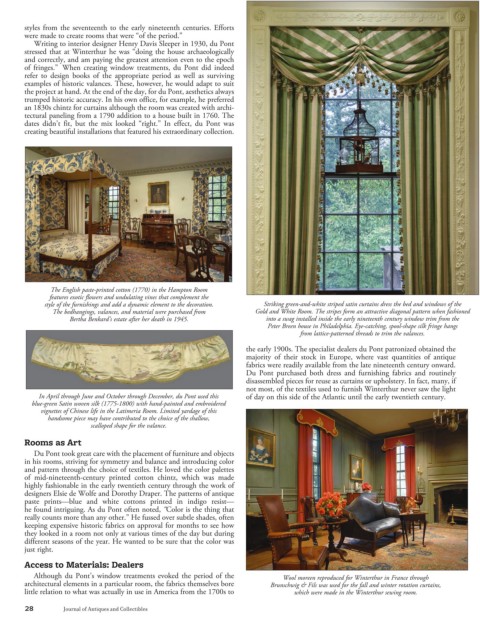

style of the furnishings and add a dynamic element to the decoration. Striking green-and-white striped satin curtains dress the bed and windows of the

The bedhangings, valances, and material were purchased from Gold and White Room. The stripes form an attractive diagonal pattern when fashioned

Bertha Benkard’s estate after her death in 1945. into a swag installed inside the early nineteenth century window trim from the

Peter Breen house in Philadelphia. Eye-catching, spool-shape silk fringe hangs

from lattice-patterned threads to trim the valances.

the early 1900s. The specialist dealers du Pont patronized obtained the

majority of their stock in Europe, where vast quantities of antique

fabrics were readily available from the late nineteenth century onward.

Du Pont purchased both dress and furnishing fabrics and routinely

disassembled pieces for reuse as curtains or upholstery. In fact, many, if

not most, of the textiles used to furnish Winterthur never saw the light

In April through June and October through December, du Pont used this of day on this side of the Atlantic until the early twentieth century.

blue-green Satin woven silk (1775-1800) with hand-painted and embroidered

vignettes of Chinese life in the Latimeria Room. Limited yardage of this

handsome piece may have contributed to the choice of the shallow,

scalloped shape for the valance.

Rooms as Art

Du Pont took great care with the placement of furniture and objects

in his rooms, striving for symmetry and balance and introducing color

and pattern through the choice of textiles. He loved the color palettes

of mid-nineteenth-century printed cotton chintz, which was made

highly fashionable in the early twentieth century through the work of

designers Elsie de Wolfe and Dorothy Draper. The patterns of antique

paste prints—blue and white cottons printed in indigo resist—

he found intriguing. As du Pont often noted, “Color is the thing that

really counts more than any other.” He fussed over subtle shades, often

keeping expensive historic fabrics on approval for months to see how

they looked in a room not only at various times of the day but during

different seasons of the year. He wanted to be sure that the color was

just right.

Access to Materials: Dealers

Although du Pont’s window treatments evoked the period of the Wool moreen reproduced for Winterthur in France through

architectural elements in a particular room, the fabrics themselves bore Brunschwig & Fils was used for the fall and winter rotation curtains,

little relation to what was actually in use in America from the 1700s to which were made in the Winterthur sewing room.

28 Journal of Antiques and Collectibles