Page 29 - joa-feb-24-rev

P. 29

Kandinsky’s treatise influenced her motivation to create and collect abstract art, believing that

non-objective art inspired the viewer to search for spiritual meaning through simple visual expression.

Following this philosophy, Rebay acquired numerous works by contemporary American and

European abstract artists, such as the artists mentioned above and Bolotowsky, Gleizes, and in

par-ticular Kandinsky and Rudolf Bauer.

In 1927, Rebay immigrated to New York, where she enjoyed success in exhibitions and was

commissioned to paint the portrait of millionaire art collector Solomon Guggenheim.

This meeting resulted in a 20-year friendship, giving Rebay a generous patron which allowed her

to continue her work and acquire more art for her collection. In return, she acted as his art advisor,

guiding his tastes in abstract art and connecting with the numerous avant-garde artists she met over

her lifetime.

After amassing a large collection of abstract art, Guggenheim and Rebay co-founded what was

previously known as the Museum of Non-Objective Art, now the Solomon R. Guggenheim

Hilla Rebay in her studio, 1946, via the Solomon Museum, with Rebay acting as the first curator and director.

R. Guggenheim Museum Archives, New York Upon her death in 1967, Rebay donated around half of her extensive art collection to the

Guggenheim. The Guggenheim Museum would not be what it is today without her influence, having

one of the largest and best quality art collections of 20th-century art.

Peggy Cooper Cafritz: Patron of Black Artists

There is a distinct lack of representation of artists of color in public and private collections,

museums, and galleries. Frustrated by this absence of equity in American cultural education,

Peggy Cooper Cafritz became an art collector, patron, and fierce education advocate.

From an early age, Cafritz was interested in art, starting from her parents’ print of Bottle and

Fishes by Georges Braque and frequent trips to art museums with her aunt. Cafritz became an

advocate for education in the arts while in Law school at George Washington University. She

began collecting as a student at George Washington University, purchasing African masks from

students who came back from trips to Africa, as well as from a well-known collector of African art,

Warren Robbins. While in law school, she was involved in organizing a Black Arts Festival, which

developed into the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington D.C.

After law school, Cafritz met and married Conrad Cafritz, a successful real estate developer.

She stated in the autobiography essay in her book, Fired Up, that her marriage afforded her the

ability to begin collecting art. She started out collecting 20th-century artworks by Romare

Bearden, Beauford Delaney, Jacob Lawrence, and Harold Cousins.

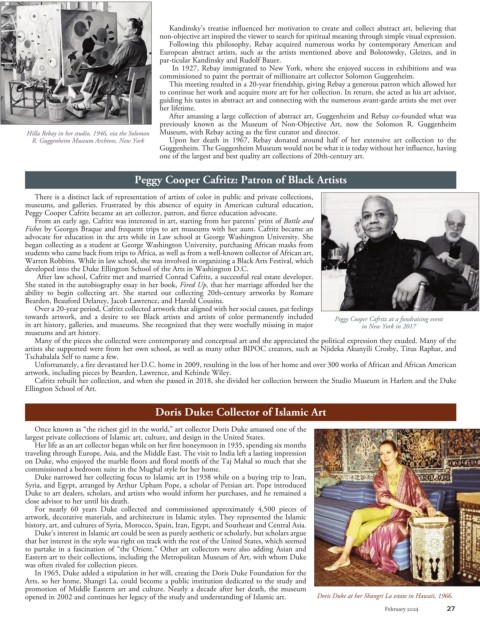

Over a 20-year period, Cafritz collected artwork that aligned with her social causes, gut feelings

towards artwork, and a desire to see Black artists and artists of color permanently included Peggy Cooper Cafritz at a fundraising event

in art history, galleries, and museums. She recognized that they were woefully missing in major in New York in 2017

museums and art history.

Many of the pieces she collected were contemporary and conceptual art and she appreciated the political expression they exuded. Many of the

artists she supported were from her own school, as well as many other BIPOC creators, such as Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Titus Raphar, and

Tschabalala Self to name a few.

Unfortunately, a fire devastated her D.C. home in 2009, resulting in the loss of her home and over 300 works of African and African American

artwork, including pieces by Bearden, Lawrence, and Kehinde Wiley.

Cafritz rebuilt her collection, and when she passed in 2018, she divided her collection between the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Duke

Ellington School of Art.

Doris Duke: Collector of Islamic Art

Once known as “the richest girl in the world,” art collector Doris Duke amassed one of the

largest private collections of Islamic art, culture, and design in the United States.

Her life as an art collector began while on her first honeymoon in 1935, spending six months

traveling through Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. The visit to India left a lasting impression

on Duke, who enjoyed the marble floors and floral motifs of the Taj Mahal so much that she

commissioned a bedroom suite in the Mughal style for her home.

Duke narrowed her collecting focus to Islamic art in 1938 while on a buying trip to Iran,

Syria, and Egypt, arranged by Arthur Upham Pope, a scholar of Persian art. Pope introduced

Duke to art dealers, scholars, and artists who would inform her purchases, and he remained a

close advisor to her until his death.

For nearly 60 years Duke collected and commissioned approximately 4,500 pieces of

artwork, decorative materials, and architecture in Islamic styles. They represented the Islamic

history, art, and cultures of Syria, Morocco, Spain, Iran, Egypt, and Southeast and Central Asia.

Duke’s interest in Islamic art could be seen as purely aesthetic or scholarly, but scholars argue

that her interest in the style was right on track with the rest of the United States, which seemed

to partake in a fascination of “the Orient.” Other art collectors were also adding Asian and

Eastern art to their collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with whom Duke

was often rivaled for collection pieces.

In 1965, Duke added a stipulation in her will, creating the Doris Duke Foundation for the

Arts, so her home, Shangri La, could become a public institution dedicated to the study and

promotion of Middle Eastern art and culture. Nearly a decade after her death, the museum

opened in 2002 and continues her legacy of the study and understanding of Islamic art. Doris Duke at her Shangri La estate in Hawaii, 1966.

February 2024 27