Madison Modern: Century House Pottery

by Donald-Brian Johnson

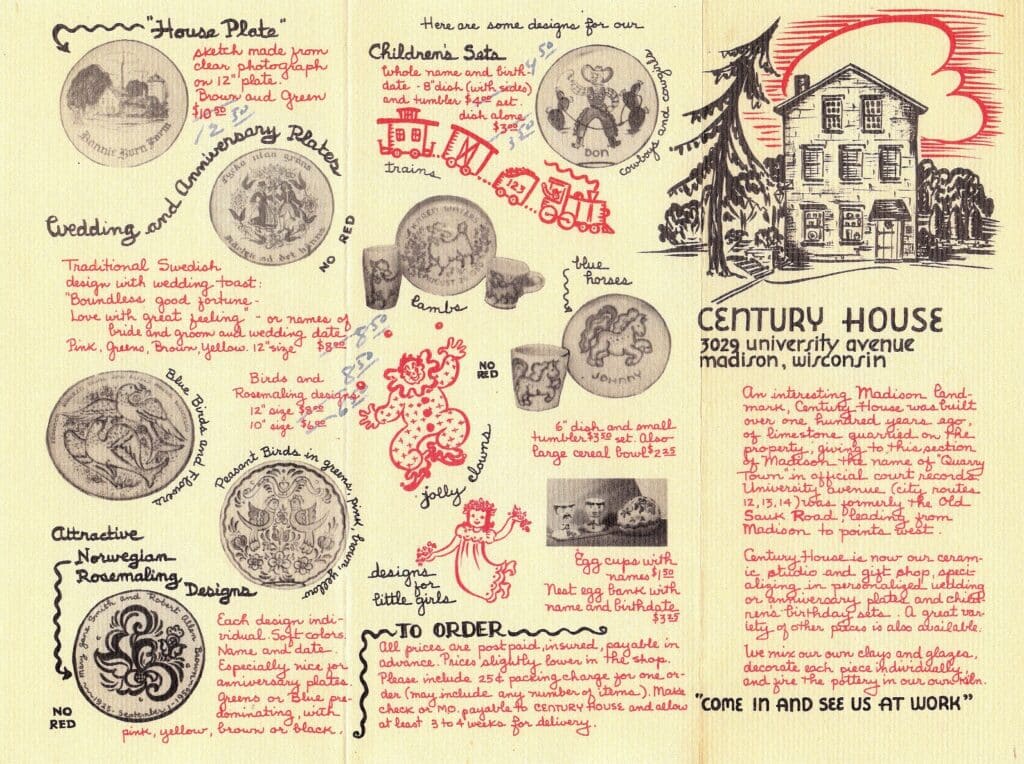

During the 1940s and ‘50s, most ceramics and pottery firms were based on the West Coast. Two of the best-loved, however, made Madison, Wisconsin, their home: Ceramic Arts Studio and Century House Pottery. Although products of both were single-fired in the kiln (unique for the time), there was otherwise little overlap. Ceramic Arts Studio specialized in figurines. The Century House mainstays were functional, yet eye-pleasing, household objects. Ceramic Arts is by far the better-known, the result of its nationwide distribution, and an endlessly varied parade of figurines designed by Betty Harrington. Century House, however, has gained its own band of aficionados, thanks to housewares which effectively reinterpret the past with a distinctly modern flair. Although eclipsed in size, Century House Pottery offered up a unique blend of mid-20th-century-modern and folk art.

The Century Begins

Century House first opened its doors in 1948, as a collaborative effort between Priscilla Jane Scalbom (“P. Jane”) and Jane Peterson (“Jane P”). The two met as fellow students at the Chicago Art Institute, and later renewed their friendship as Madison Public School art

teachers. The goal of their new enterprise: to create an environment in which “the two Janes,” as well as other local artists, could design, create, and hopefully sell their work.

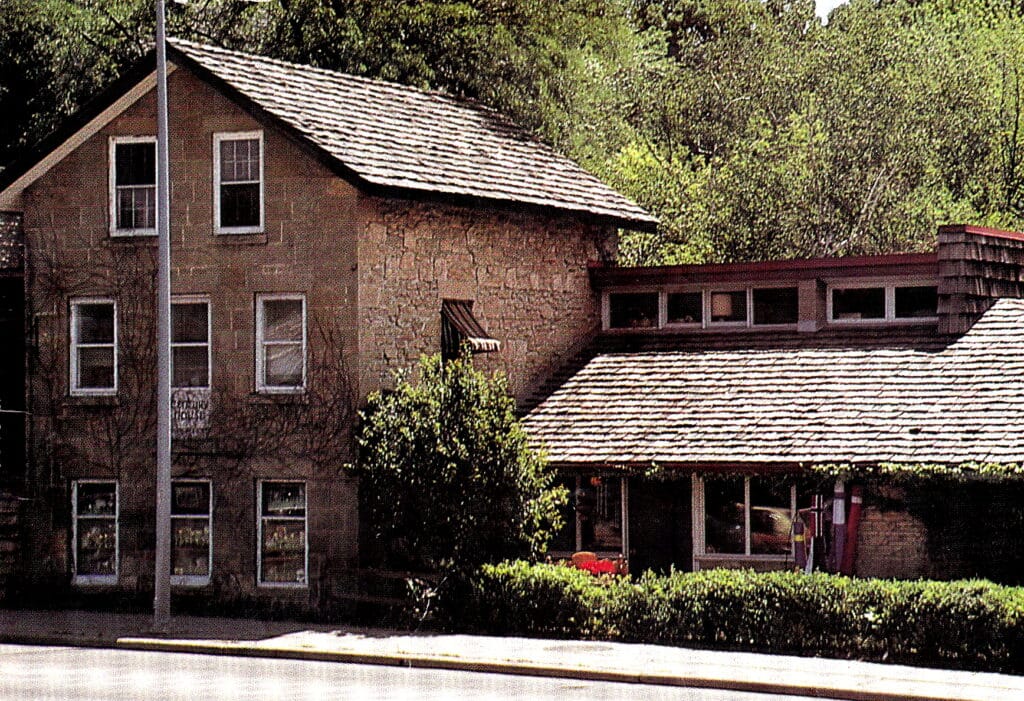

The “Century” name came from the building P. Jane purchased for $15,000 to house their venture: a crumbling stone edifice, built in 1836, which had previously housed the Century House Tavern. The two Janes took on the restoration project themselves, pouring concrete and replacing missing stones. In the beginning, their do-it-yourself work was often interrupted. Thirsty former tavern customers paid visits, and left in disappointment after learning that their favorite watering hole was no more. To finance repairs, the Janes continued their teaching careers, as well as moonlighting at odd jobs. Money was definitely tight: as P. Jane later recalled, in the beginning their “ceramics income” was just 25 dollars a week!

Although Jane Peterson was already married with a home of her own, the then-single Jane Scalbom saved additional pennies by setting up housekeeping on the second floor of Century House. At street level were the Century House shop, kiln, and glaze-mixing lab; the third floor was home to P. Jane’s art studio.

A bare-bones budget meant that inventiveness was often called for. One of the team’s most successful brainstorms: repurposing a second-hand washing machine as a clay mixer. The Century House kiln was a horizontal one, unusual for the time. An innovation designed by Illinois art potter Harold Ipsen, the horizontal kiln featured a car on a track, which meant pottery could be pushed in and out for firing. (Previous upright kilns required the operator to actually go into the kiln for loading and unloading.)

When Century House opened its no-longer-rundown doors on October 18, 1948, the gift-buying public was in for a treat. In addition to ceramics by “the two Janes,” Century House also served as a sales outlet for such hand-crafted items as woodcarvings, music boxes, candles, and placemat sets, all the work of other Madison-area artists. Among the best-known: Aaron Bohrod, who later achieved renown for his still-life collage paintings. Century House pieces with the Bohrod signature are extremely rare, and especially prized by today’s collectors.

Two Centurions

In 1949, P. Jane married ceramist Charles “Max” Howell. Max had grown up in Madison and studied at the University of Wisconsin until World War II service intervened. Following the war, Max continued ceramic study in California, eventually finding employment with the Dick Knox Pottery of Laguna Beach, as principal mold-maker. Intent on applying his talents to his own pottery, Howell returned to Madison, meeting P. Jane shortly after the opening of Century House. Max became the new firm’s mold-maker, and in 1951, when Jane Peterson and her husband moved from Madison, the Howells (now simply “Jane and Max”) assumed proprietorship of Century House.

Their personal team-up also proved successful professionally. Jane was a gifted designer-decorator, using liquid slip to hand-paint her designs on unfired greenware, which, after drying, was spray-glazed. (Early pieces featured incised, rather than painted, decoration.) Max, skilled at mold-making and glaze-blending, also became adept at loading and firing the Century House kilns. By expanding to two kilns, pottery could be fired in one while the other was being loaded, keeping production moving along on an even keel. To ensure a smooth operating schedule, Jane and Max literally lived “above the store.” For fourteen years, as their family expanded to include four children, “home” meant the upper levels of the Century House building; a trap door was the only way to reach the third-floor master bedroom. Jane’s artistic inventiveness extended to the living quarters: a colorful, hand-painted “family tree” over the bathtub envisioned each family member as a bird.

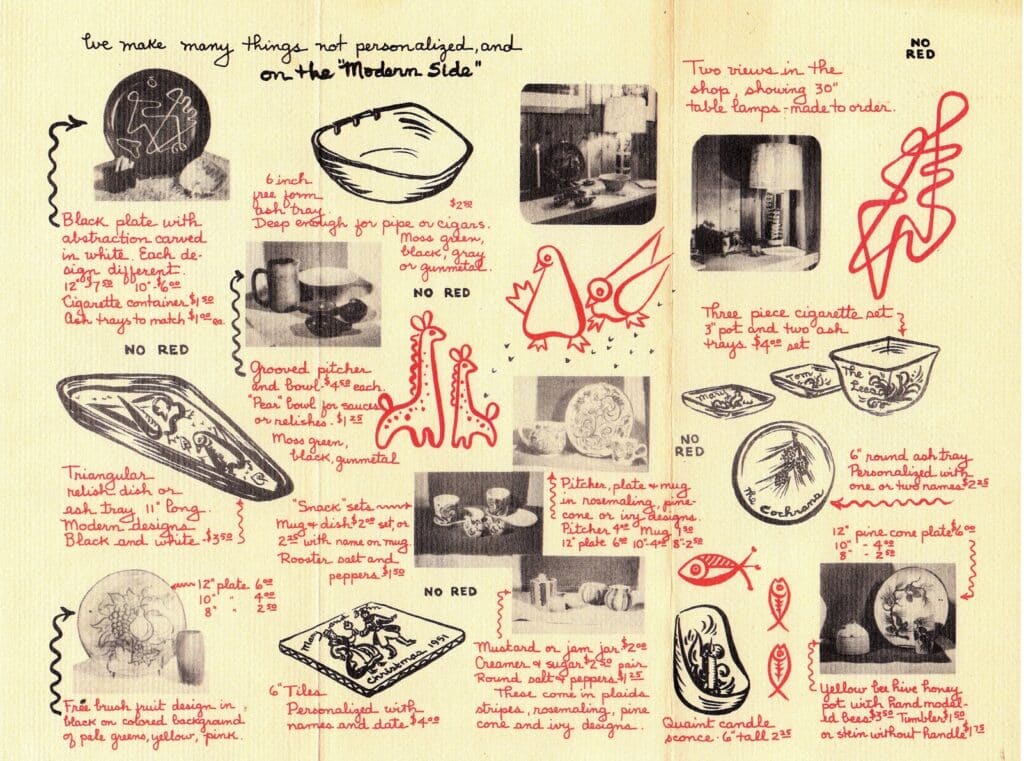

Sugar and creamer with bird motif, 1953. 2-3/4” h.; 3-1/2” h. $25-35/pr.

From the start, a visually arresting assortment of functional items, such as plates, bowls, mugs, cups, jars, and ashtrays, proved popular with buyers. To increase customer traffic, Jane also began offering “personalized” pieces, an option that would not have been possible in a high-volume environment. Soon, customized Century House ceramics became Madison must-haves for special occasions: baby showers, birthdays, weddings, and anniversaries. Names and dates were incorporated into the basic design, making each piece literally “one of a kind.” Some inscriptions proved more challenging than others: a punch bowl, for instance, featured a complete (and apt) quotation from Ecclesiastes: “A man hath no better thing under the sun than to eat and drink and to be merry.”

Although some Century House pieces carried a paper identifying label or a painted logo on the base, most featured the incised base marking: “Century House Pottery,” often accompanied by the date, and the decorator’s name or initials.

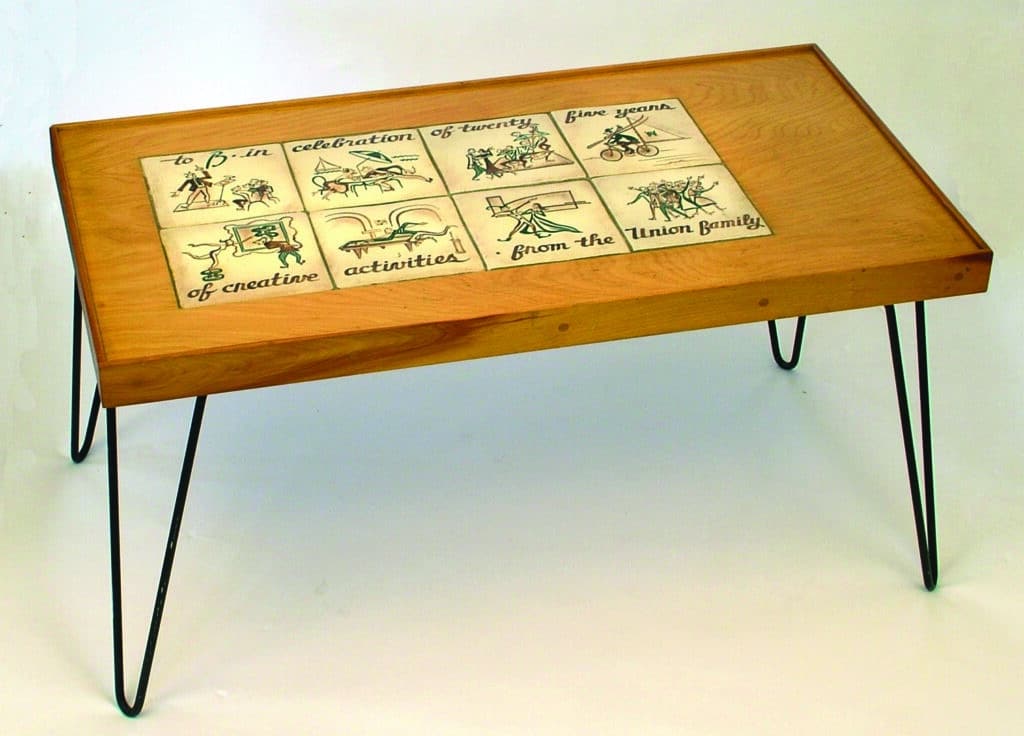

Always on the lookout for products with customer appeal, the Century House pair expanded their inventory to include custom-crafted touches, such as wooden bases, jar lids, and decorated ceramic lamps. The Howells also accepted commissions for special projects, including dinnerware for local restaurants and decorative tiles for home interiors. In addition to the standard Century House shapes and products, clients could also request customized designs. (Wisconsin’s governor even ordered personalized ashtrays for distribution to ardent supporters.) One of the studio’s most unusual assignments: a tile-topped table created to mark the 25th anniversary of the University of Wisconsin’s Memorial Union building, each tile depicting a different creative activity hosted by the Union.

Ashtray with cat and kittens, 1957.

6” square, $50-60.

Jane Howell’s ceramic illustrations ran the gamut of what would appeal to the mid-twentieth-century buying public. For those in search of the traditional, there were heartwarming images of frolicking lambs, coy kittens, and little tykes skipping rope, or decked out in cowboy attire. Non-figural favorites included dinnerware decorated with pine cones peeping through sweeping branches, oversized leaves, or trailing strands of ivy.

Modernism proved a particularly reliable Century House staple. Schools of abstract fish, flocks of abstract birds, and fluttering clusters of abstract insects were arranged by Howell with geometric precision, appealing to those whose ceramic whims tended to the less cozy.

There was even the occasional nod to old school folk art, in the form of rosemaling. Those designs were a specialty of Zona Liberace, the stepmother of the famed pianist. Zona had previously served as Head Decorator for Ceramic Arts Studio. When CAS closed

its doors in 1955, she put her talents to work for Century House.

A Norwegian tradition, rosemaling utilizes a colorful mixture of floral ornamentation and scrollwork to create elaborately flowing patterns. The tried-and-true Norse art found new popularity when exported to America in the early twentieth century by wagon painter

Per Lysne. When wagons went out of fashion, Lysne found a new canvas for his artistic pursuit: brightening everyday household objects with his lively designs. Others (including Zona) followed Per’s cue, adorning the new with the old, and generating plenty of consumer interest. Rosemaling proved particularly well-suited to the custom items produced by Century House: its beautifully intricate yet indeterminate stylings enhanced, rather than deflected attention from, an object’s main focal point: the personalized inscription.

Personalized wedding plate with stylized doves, 1959. 12-1/4” d., $65-75.

Tile-topped coffee table with scenes of activities at the University of Wisconsin Memorial Union, 1953. 36” l., x 19” w. x 18-1/2” h. $350-400.

Green glaze punch bowl and cups, 1951. The incised verse encircling the rim interior is from Ecclesiastes 8:15: “A man hath no better thing under the sun than to eat and drink and to be merry.” Bowl, 13” d. x 5-3/4” h.

Turn of the Century

With the flood of mass-produced imported giftware during the 1950s, Century House, like many similar firms nationwide, found it impossible to compete. Individualized ceramic-making was labor-intensive; increasing prices to a level necessary to recoup production expense was not a viable option for a firm without nationwide distribution. Century House ceased pottery production in 1963, refashioning itself as a distributor of Danish modern furniture and gift items. In that very different capacity, Century House continues to thrive today, from its same historic Madison location.

What explains the appeal of Century House ceramics? Well, there is, of course, that “rarity”

factor. During its peak years, Madison’s Ceramic Arts Studio turned out nearly 500,000 ceramic figurines annually and employed a staff of 50. The Century House roster never numbered more than 5 (including the owners). The result: a much tinier handcrafted production output,

marketed primarily to local clientele.

But rarity alone does not ensure longevity. What really draws in collectors is the Century House blend of the primitive and the modern. Jane Howell’s whimsical illustrations achieve their impact through an economy of line and placement, bold dark brushstrokes against neutral backgrounds. They are quite deliberately childlike, with no attempt at photographic realism. The barest minimum of detail—the stripes of a tabby cat … the lasso of a young cowboy … the mop-like mane of a lion—defines an image. Even the rustic decorative flourishes of rosemaling are utilized with an up-to-date sensibility. Howell dusts off the past, infusing it with an irresistible dose of timelessness.

A 1949 Century House ad noted, “there are so many lovely things that it’s hard to choose between them all.” Fortunately, today’s collectors don’t have to. Keep your eyes peeled, and when you see a piece, snap it up. After all, ceramics like those by Century House only come around … well, once in a century!

Photos courtesy of the Wisconsin Pottery Association, from its publication, Century House Pottery: 1948-1963 (principal photographers: Art and Eileen Wendt). The book is available through the WPA website: wisconsinpottery.org

Photo restoration by Hank Kuhlmann

Donald-Brian Johnson is the co-author of numerous Schiffer books on design and collectibles, including Postwar Pop, a collection of his columns. Please address inquiries to: donaldbrian@msn.com