China Plates: Intentional Collectibles

Article and photos by Donald-Brian Johnson

“What should I do with these?”

That’s the question I’m often asked by folks who’ve inherited a “collection of collections.” Sometimes it’s phrased less delicately: “How the heck do I get rid of this stuff?” I generally respond with my own question: “Do you like it?” Many times, the answer is “no.”

Usually, the “stuff” they’re talking about falls into the category of “intentional collectibles.” These are items that were created with just one purpose in mind: to be collected. They differ from items that were created for another purpose—say, for instance, antique kitchen implements—and only later attracted collector interest.

“Intentionals” can range from Shirley Temple dolls to Presidential bobbleheads. Often, they are china plates. These are the plates you’ll see advertised in magazines at the grocery store checkout counter, usually with the enthusiastic header “edition extremely limited!” Want to celebrate beloved artists, such as Terry Redlin or Norman Rockwell? To learn all about “Birds of the World?” To relive scenes from The Sound of Music? Modern collectible china plates cover themes like these, and an infinite variety more. If you like them, and want to assemble a collection, great! However, if they’re part of the “stuff” you’re “trying to get rid of,” the options are limited. Which is too bad, because collectible china plates have a long and varied history.

Painted china plates made their first documented appearance in 9th-century China (hence the name), and eventually became a desirable European trade item. By the 18th century, Europeans had learned the secret of creating porcelain, and began turning out their own decorated china plates, many of which had the look of oil paintings. During the reign of Queen Victoria, plate painting became a popular ladies’ “parlor craft.” Here’s how Letts’s Household Magazine put it, in 1884:

“China-painting affords amusement for the girls in the family during the hours their brothers and fathers leave for business. To many such ladies, who have nothing better to do than novel reading, this method of filling their time will be esteemed a great boon. Doubly so, since their work may sold at a profit to increase their pin-money, or be given to some bazaar for charitable purposes.”

Letts’s consigned china painting to the very comfortably-situated few. However, during the heyday of the painted plate (1880-1920), manufacturers, both in the United States and abroad, employed a multitude of less financially fortunate, yet remarkably skilled women, to paint plates. These early collectibles often focused on nature-based themes, such as flowers or scenic landmarks, tasteful enough for display in a turn-of-the-20th-century home. As demand grew, the artists moved from freehand painting to stencils, speeding up production and ensuring uniformity of design. Later developments, such as transfer printing, screen printing, and lithography, made mass production possible, but eventually replaced individual paintwork. Intended for display, plate diameters ranged from 8 to 10 inches.

“The Snowman,” a 1985 release by Royal Copenhagen.

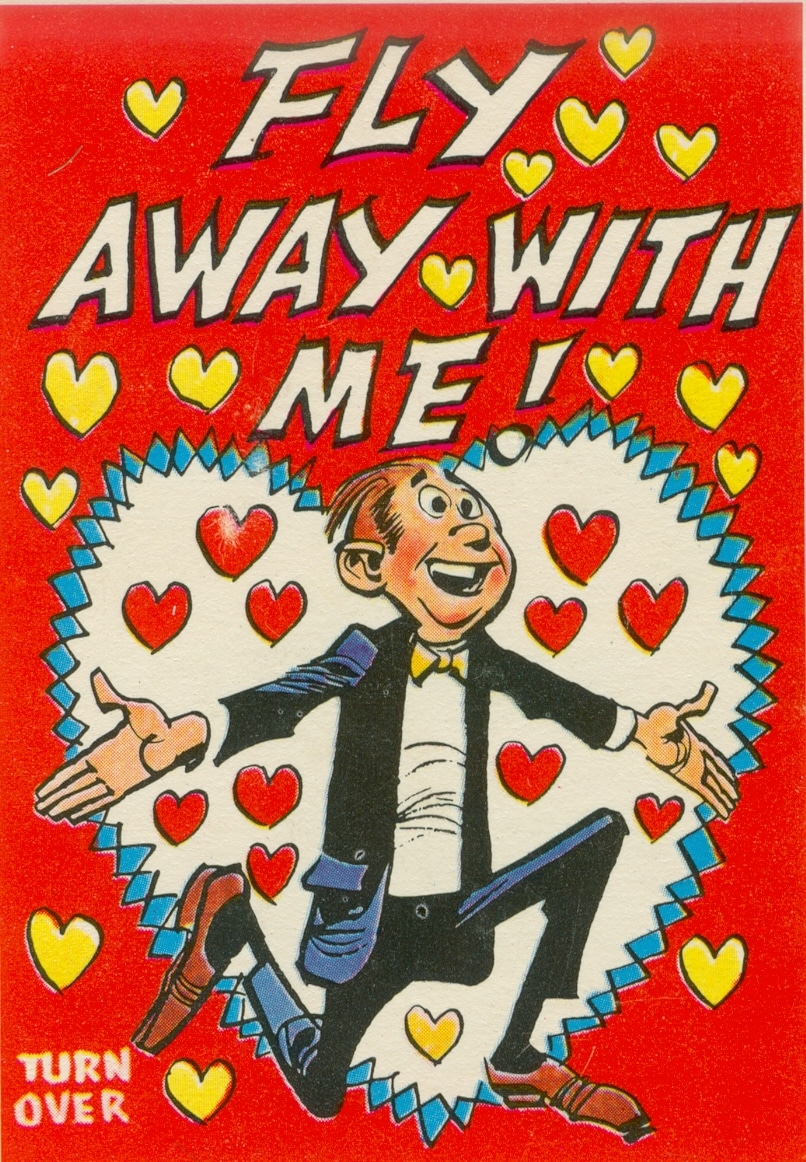

The first plate regarded as a true “modern” collectible focused on a theme still popular today: Christmas. Bing and Grondahl’s “Behind the Frozen Window” was released in 1895, and yes, it was a “limited

edition.” B & G’s familiar blue-and-whites have continued to celebrate the season into the present. Among other familiar names eventually joining the porcelain plate parade: Royal Copenhagen (more Christmas); Wedgwood; Royal Doulton; Hummel; and those magazine favorites, the Bradford Exchange, Danbury Mint and Franklin (Mint) Porcelain. Collectible china plates were also issued on a much smaller scale to recognize various localities, or to promote local businesses.

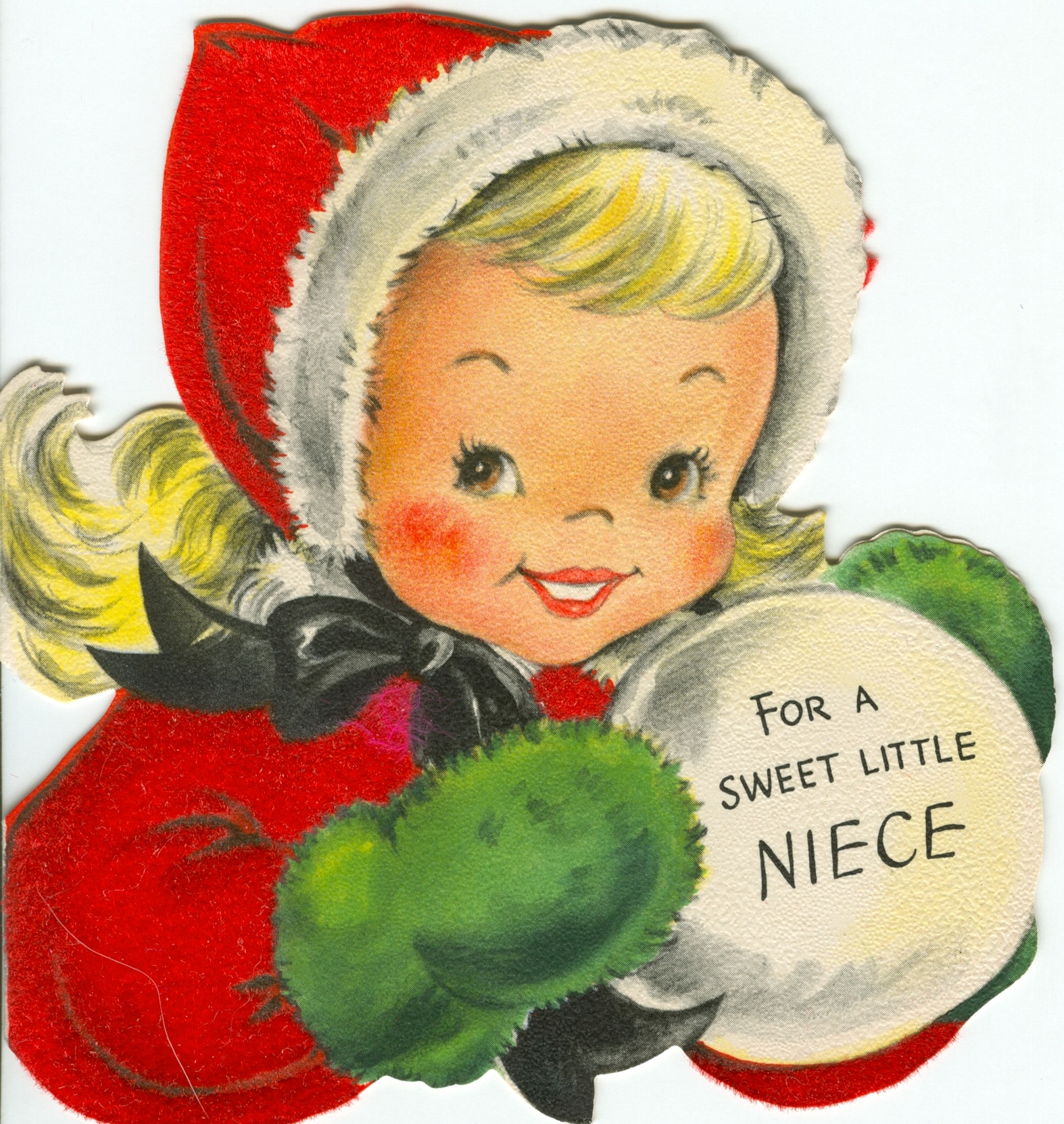

1976 United States Bicentennial plate.

The pewter rim surrounds a china insert celebrating Betsy Ross.

But back to the main question: “what to do with them?” First, a hard fact to face: if you resell the plates, you will never—ever—get back their original purchase price. (After all, that “limited edition” may have been “limited” to a million.) A quick check of eBay’s “sold” listings indicates the majority of mass-market collector plates issued since the 1980s sell for well under $10 each. Nature-themed plates from the early 20th century fare better, as do plates which appeal to specific interest groups—there always seems to be a Star Wars fan in need of another Star Wars collectible. Even these, however, rarely top $100.

If maximum sales prep for minimal rewards has no appeal, donating to a charitable resale source is always a worthwhile option. But before making a final decision, you may really want to think it over. Those china plates may mean nothing to you. But they meant something to Grandma. And who knows? That “stuff” might, someday, mean something to your kids. Grandma would be proud.

Photo Associate: Hank Kuhlmann

Donald-Brian Johnson is the co-author of numerous Schiffer books on design and collectibles, including Postwar Pop, a collection of his columns. Please address inquiries to: donaldbrian@msn.com