JUST AN OLD CHRISTMAS CARD: Celebrating a Holiday Tradition

Story and photos by Donald-Brian Johnson

When does the Christmas season really begin? When the first department store pipes in the first velvety Bing Crosby holiday favorite? When the first hundred twinkling lights go up on that big house down the street? When the first grocery store parking lot becomes a firry wonderland of ‘get-‘em-while-they-last’ freshly-cut Christmas trees?

For many, just one thing, and one thing only, marks the official onset of yuletide revelry. You can’t predict exactly when it will happen, but suddenly, without warning, the happy day arrives. The mailman pays a visit and, in amongst the usual deluge of bills, ads, and credit card offers, your daily mail coughs up something out of the ordinary. Maybe it’s an envelope dotted with stenciled snowflakes. Maybe there’s a grinning snowman on a return address label. Maybe you spy an envelope flap, carefully glued down with Christmas Seals.

But whatever the clue, you know, even before opening it, exactly what you’ve received. It’s a Christmas card—the first one of the season. Let the holidays begin!

The modern tradition of exchanging commercially-produced Christmas cards has only been with us since 1843. But even before then, each generation found its own unique way of extending season’s greetings. Ancients at the dawn of time met annually at the winter solstice; amidst all the dancing and sacrificing came the exchange of seasonal good-luck charms. For fifteenth century Germans, the exchange focus was on the devotional: Andachtsbilder, cards adorned with an image of a cross-bearing Christ Child, inscribed with wishes for “ein gut selig jar” (“a good and blessed year”).

English schoolchildren in the early eighteenth century were assigned the task of creating their own Christmas-like cards. These annual “Christmas Pieces” also served as progress reports of a sort. Personal holiday messages, painstakingly handwritten on sheets of paper with elaborate engraved borders, let Mum and Dad see just how well the penmanship was progressing (perhaps determining how well-filled Santa’s gift bag would be).

Although technically not “Christmas cards,” the “trade cards” of the early 1800s were their immediate precursor. Tradesmen handed out these cards free of charge year-round, with the purchase of such staples as coffee and tea. The card illustrations reflected seasonal themes; around the holidays, that meant lots of Santas and snowy landscapes, just right for

pasting into that staple of the Victorian home, the “parlor album.”

What prompted the first commercially-produced Christmas card? The same things that prompt so many innovations: too many things to do, and too little time to do them in.

Sir Henry Cole, director of London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, had a long-standing tradition of sending handwritten holiday greetings to family and friends. But, by 1843, that circle had widened. Sir Henry’s hand grew tired, and his patience thin. Inspiration struck: he commissioned artist friend John Calcott Horsley, a member of the Royal Academy, to create a card that could be lithographed, colored by hand, and sent to those on Sir Henry’s list. “Extras” in the initial printing of 1000 were then made available for sale to the general public, at a shilling apiece.

Horsley designed a 3” x 5” card illustrating three scenes. A merry-making family enjoying a holiday toast filled the central panel; highlighting the true spirit of the season, the side panels featured charitable folk feeding the hungry, and clothing the naked.

Early Victorians, however, were easily shocked. The cards were roundly condemned, not for their depictions of the starving and the unclothed, but because one of the figures shown sipping wine in the central panel was a child. Horsley was criticized for “fostering the moral corruption of children,” and the cards were quickly withdrawn from the market; today, only about a dozen remain.

While images of wine-swilling youngsters may not have appealed to buyers in the mid-1800s, the idea of the ready-made Christmas card did. Over the next several years, the custom of card exchange grew in popularity, although with illustrations of more palatable seasonal subjects, such as holly, ivy, and blissful sleigh rides.

The expense of lithographed, hand-colored cards initially meant that only the wealthy could afford them. Eventually, thanks to the use of less costly paper and the development of the steam printing press, production costs plummeted, bringing the price of a Christmas card within the reach of almost every budget. And, thanks to England’s Postal Act of 1840, even mailing a Christmas card was extremely affordable: postage was just a penny, to any destination in the United Kingdom. A new and destined-to-endure holiday tradition was soon underway and flourishing—at least on the far side of the Atlantic.

In the United States, however, those sending “season’s greetings” had to make do with imported cards until 1875. That’s when Louis Prang, the “Father of the American Christmas Card,” began to sell them domestically. In 1850, Prang set up shop in New York, refining

skills acquired as a printer in his native Germany. Among those refinements: significant contributions to the technique of chromolithography. Prang’s “chromos” utilized zinc plates for color printing, and proved much less expensive than previous methods of color printing.

Prang initially exported his “chromos” for sale in England, but noting the increased demand for imported cards, he introduced them on American shores in 1875. Thanks to the miracles of mass production, and an efficient, inexpensive, postal system, the Christmas card tradition caught on here just as quickly as it had overseas; by the 1880s, Prang’s firm was producing nearly five million cards annually.

Through the first decades of the twentieth century, the artistic style and themes favored by Prang—cherubs, children, illustrations of beautiful women, and lush floral arrangements—dominated the Christmas card market. Similar themes proved just as popular with Prang’s card-printing competitors. Interestingly enough, the image on a Prang (or Prang-like) Christmas card did not necessarily have to relate to the holidays: with a change of printed message, the same doe-eyed lovely, or bouquet of blossoms might turn up several months later on a Valentine.

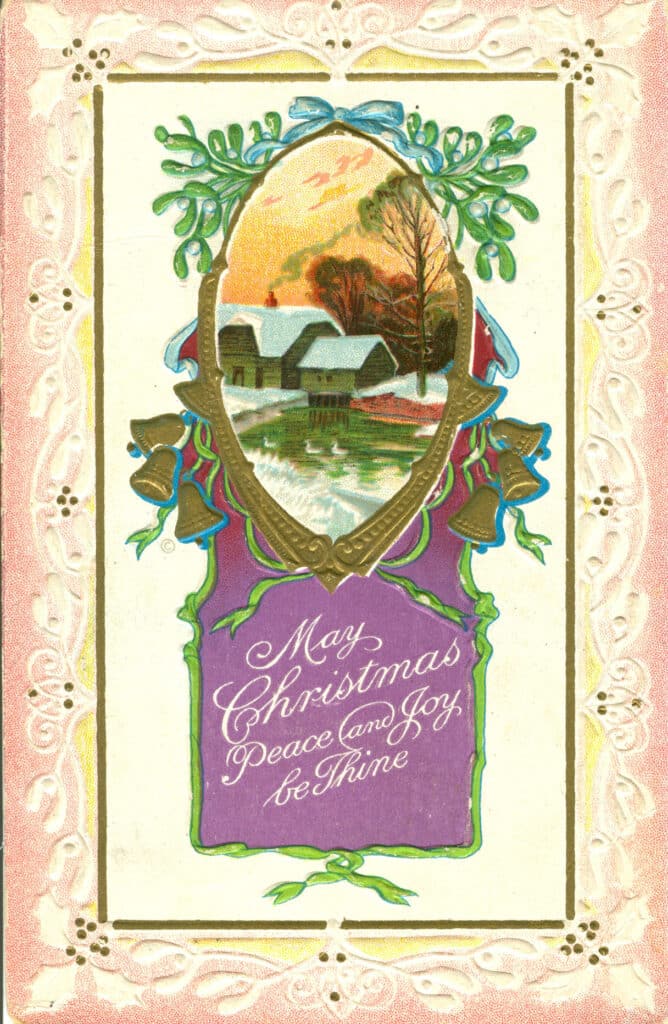

Exceptions to the Prang-influenced card designs of the late 1800s and early 1900s were cards created by popular children’s author and illustrator, Kate Greenaway. Her Christmas cards were like no others. Many were lavishly decorated with fringe and satin. Some were cut into shapes, such as bells or candles; others were fan or crescent-shaped. There were Greenaway puzzle and map cards, and cards fitted with squeaking noisemakers. Greenaway even developed an early version of the pop-up: opening the card revealed a three-dimensional mini-manger, or perhaps a pair of ice skaters, scarves flapping in the wind.

Because of their intricate and novel designs, Kate Greenaway cards are among the most

desirable (and expensive) Victorian paper holiday collectibles.

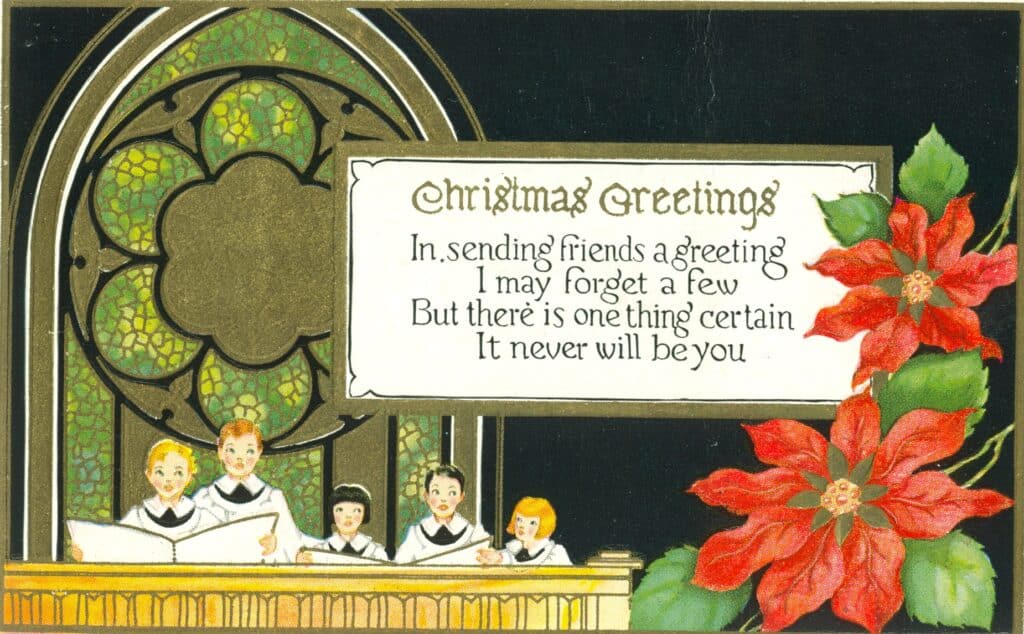

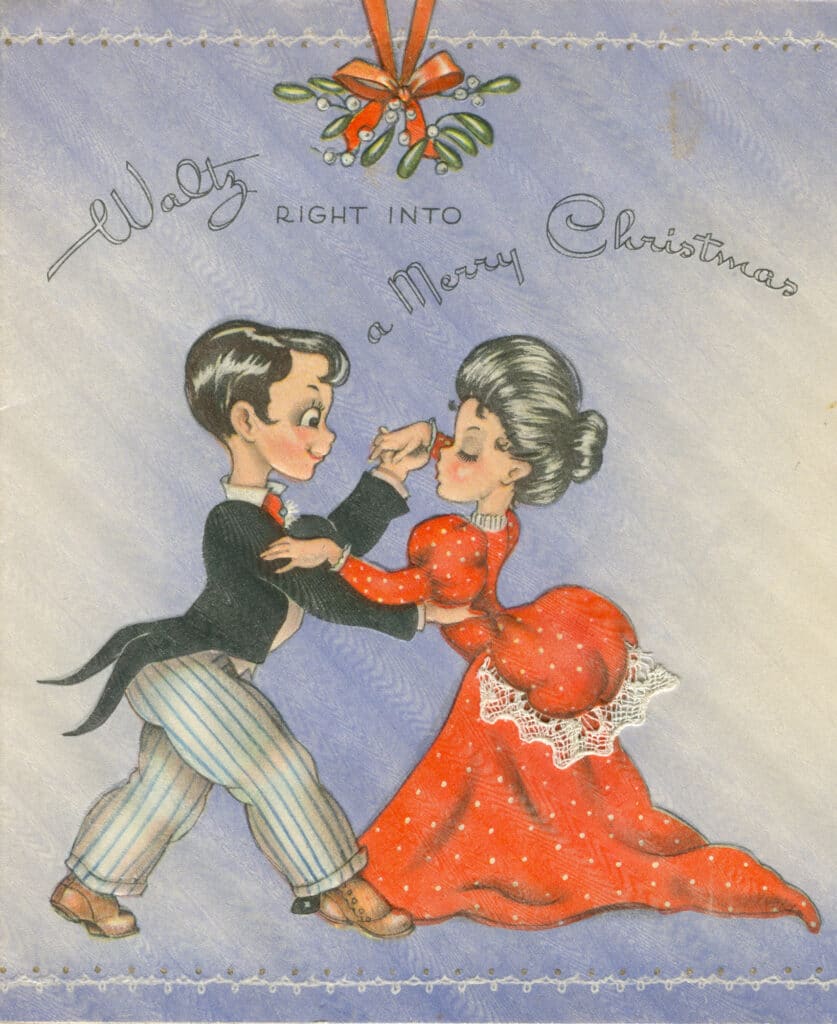

By the 1920s, a Christmas card thematic pattern, still in vogue today, had become fairly well established: the cards offered up a unique blend of nostalgia, sentiment, and season-specific visuals. Although sometimes laced with humor, each and every one had the same overriding primary purpose: to tug, sometimes subtly (and sometimes, not so subtly), at the heartstrings.

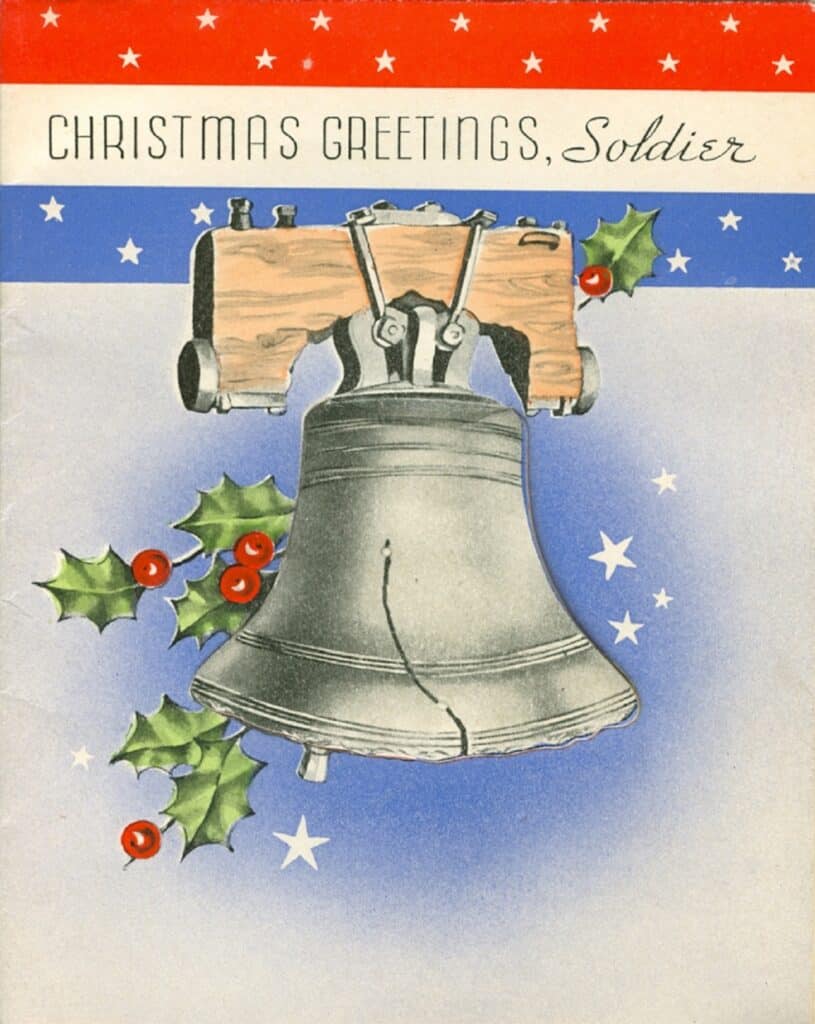

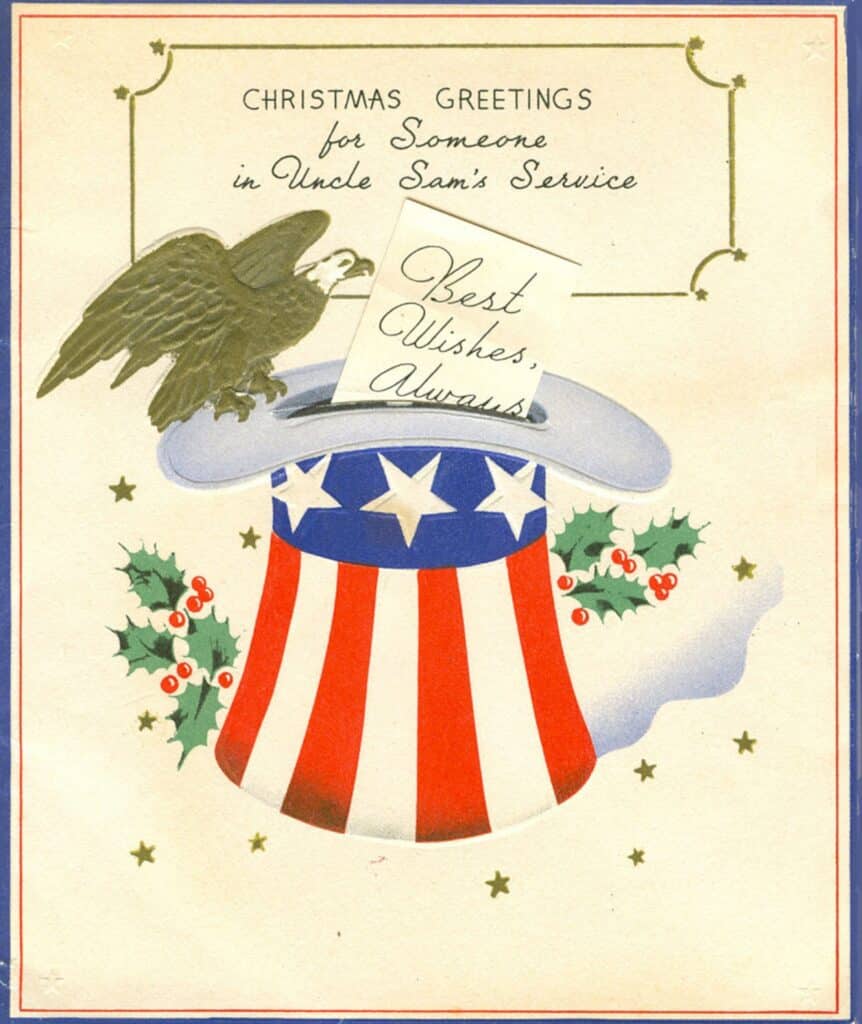

Holiday wishes became particularly poignant during World War II, as greetings were sent to friends and family members overseas. In addition to its primary function, the holiday greeting card of the 1940s played another important role: keeping morale high, both at home and abroad.

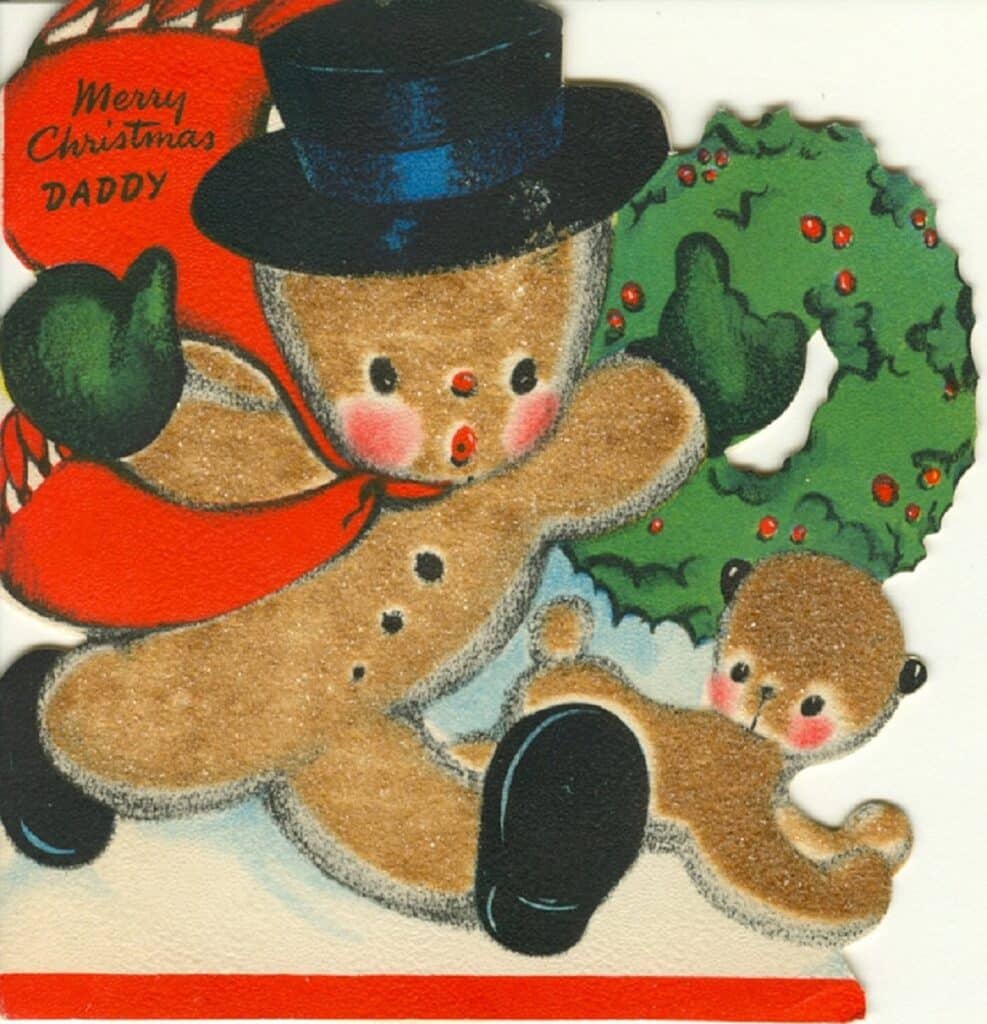

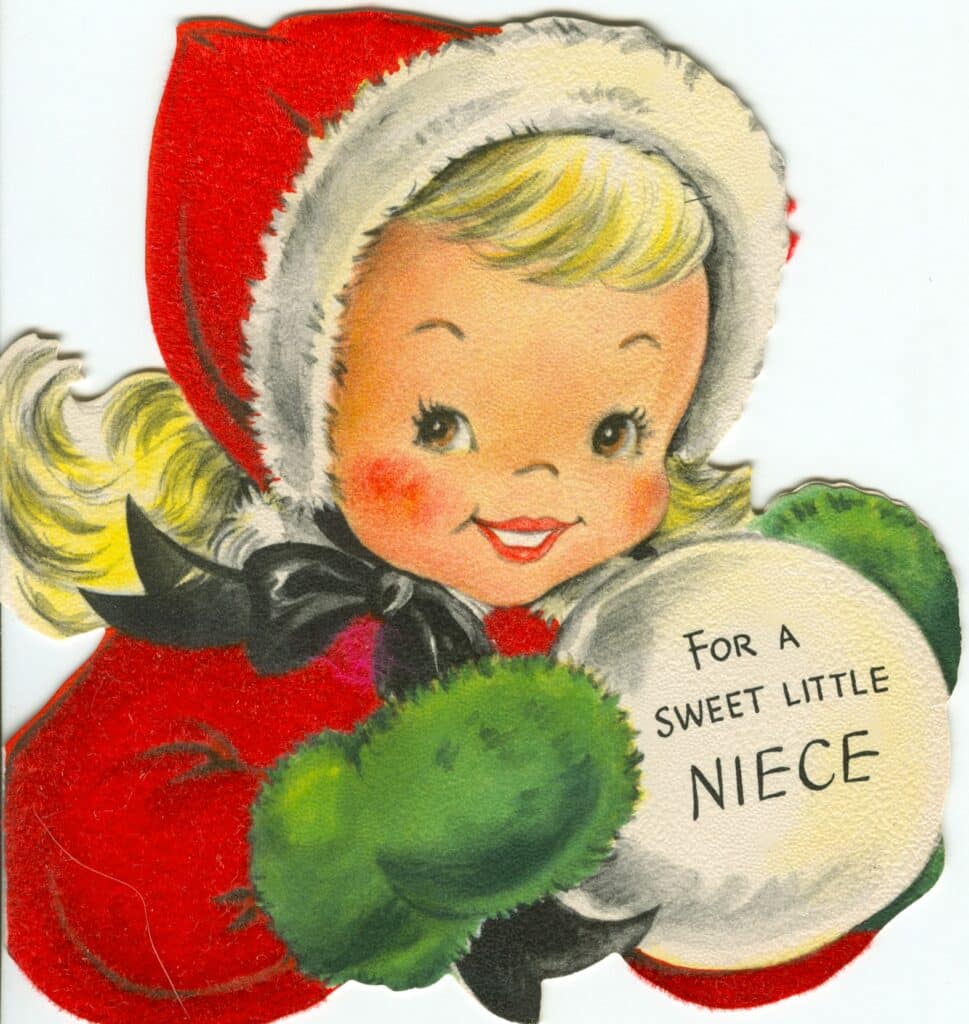

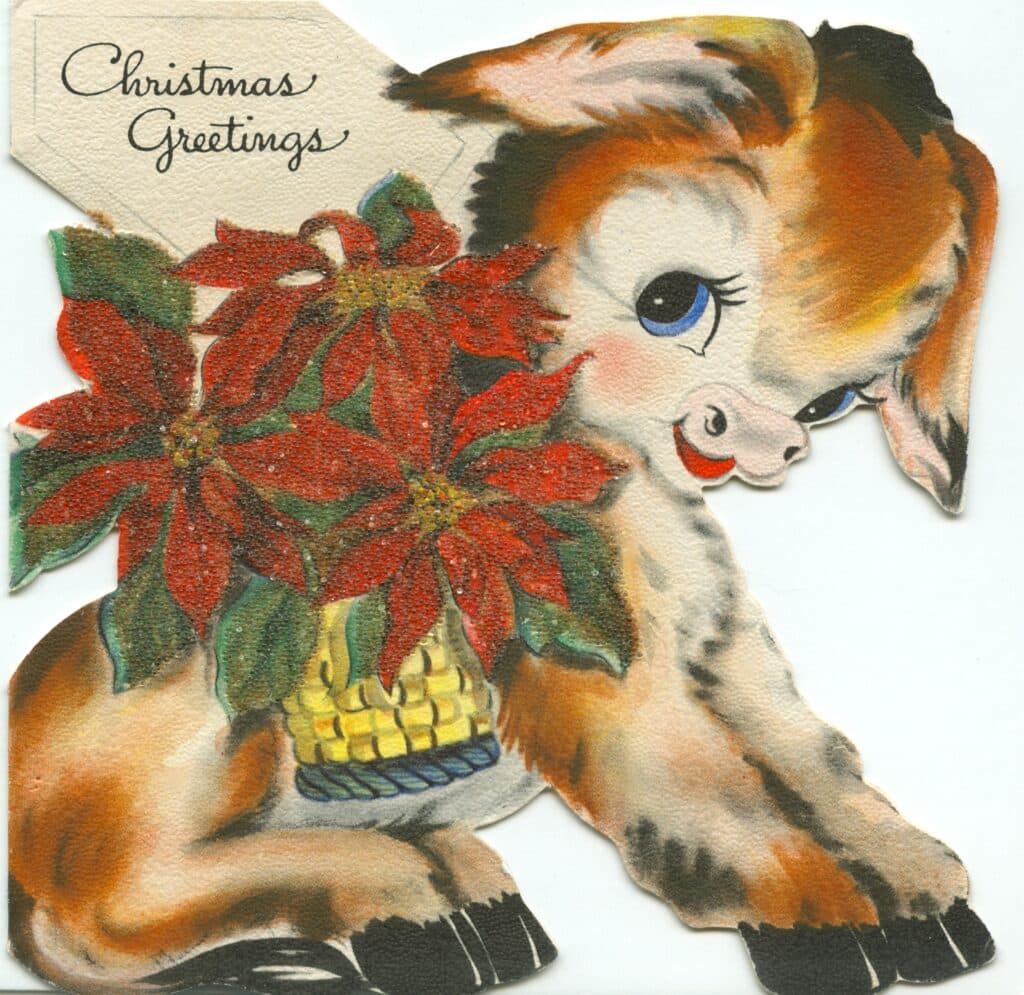

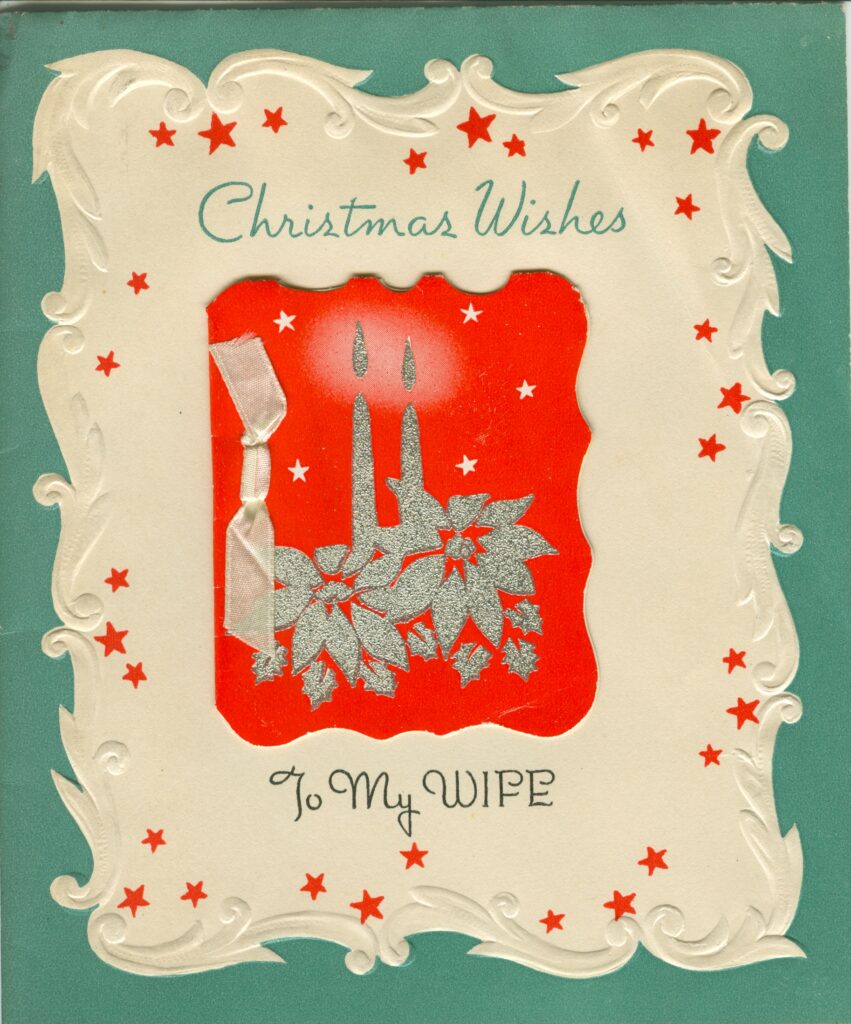

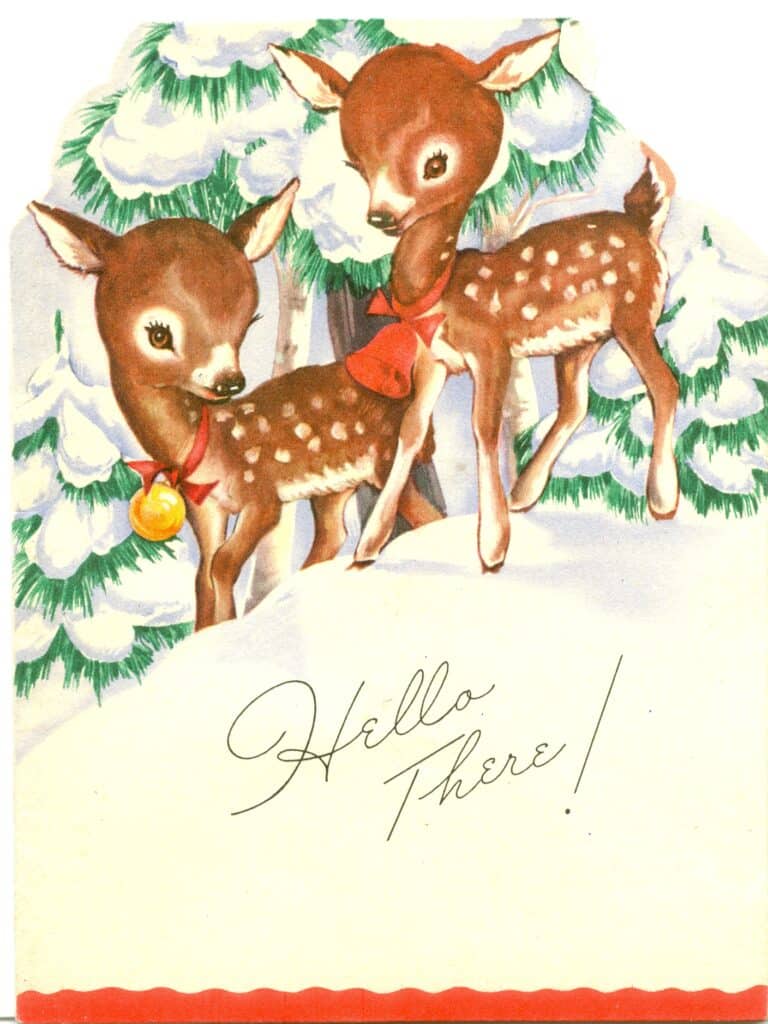

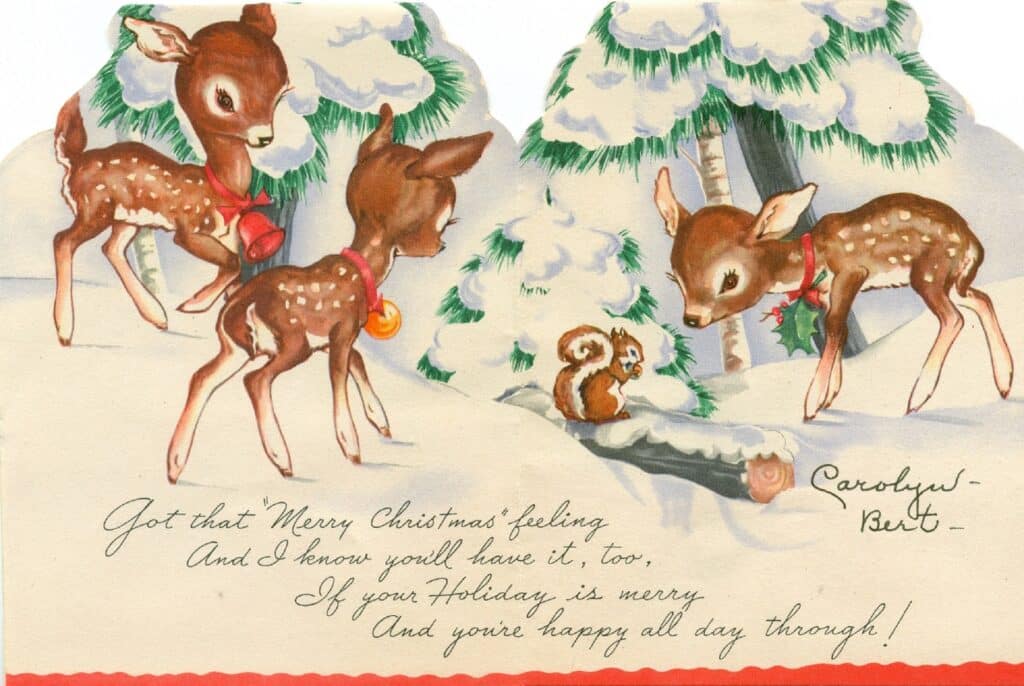

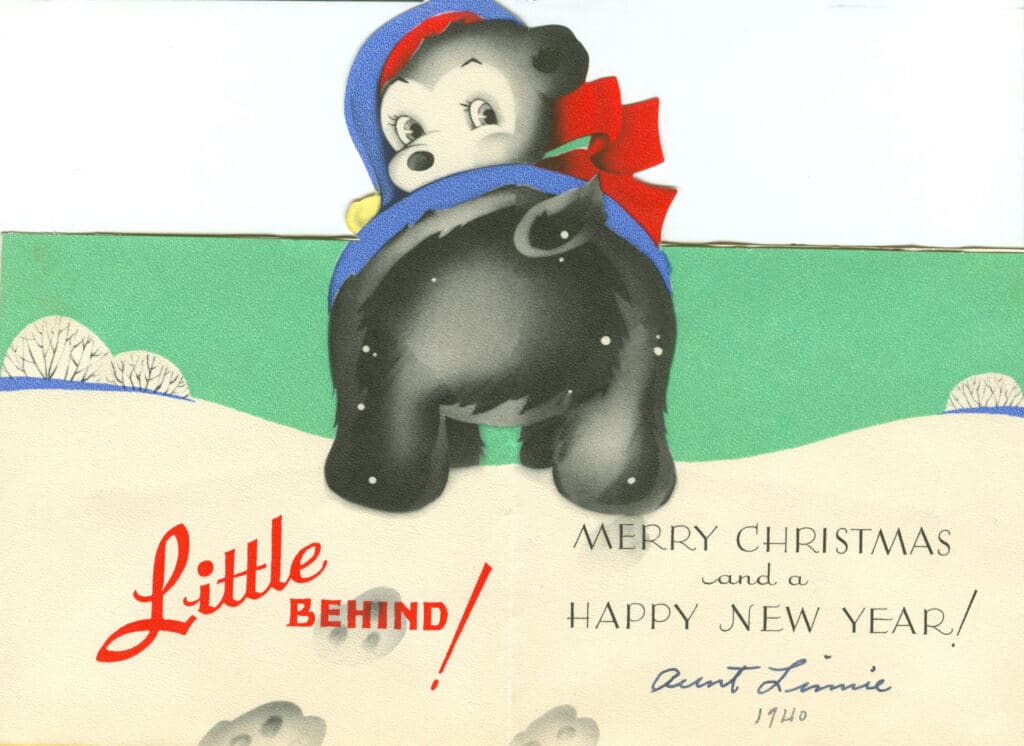

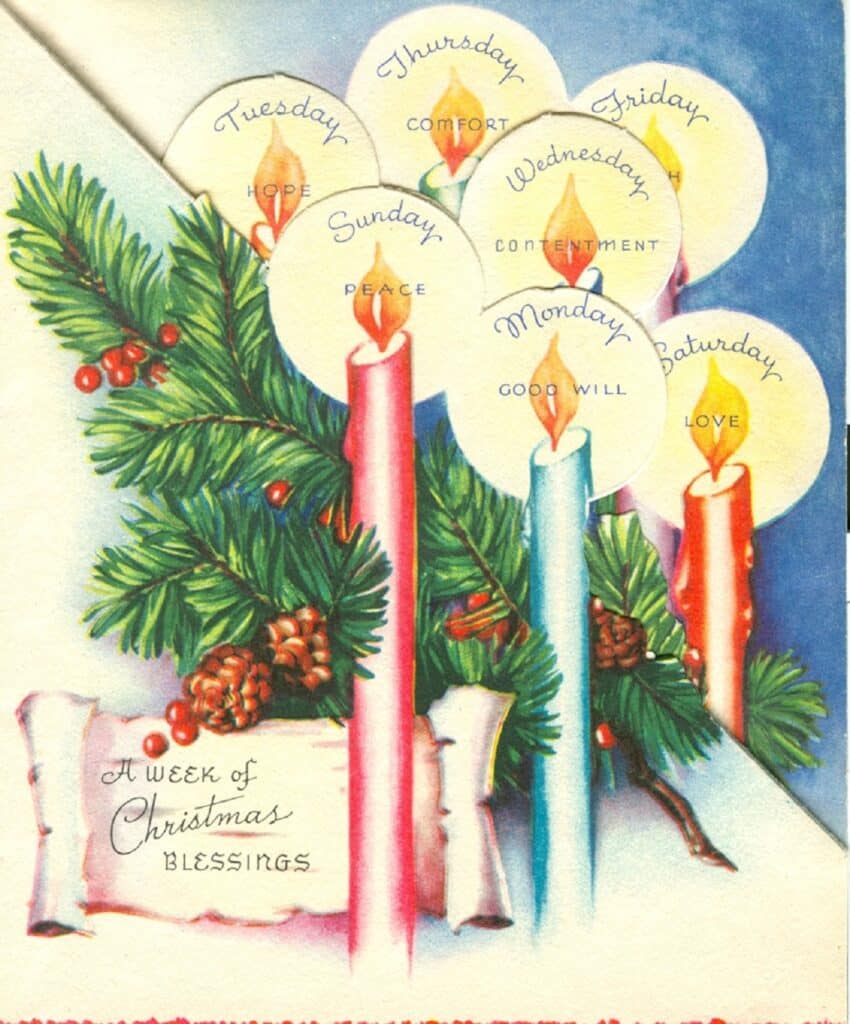

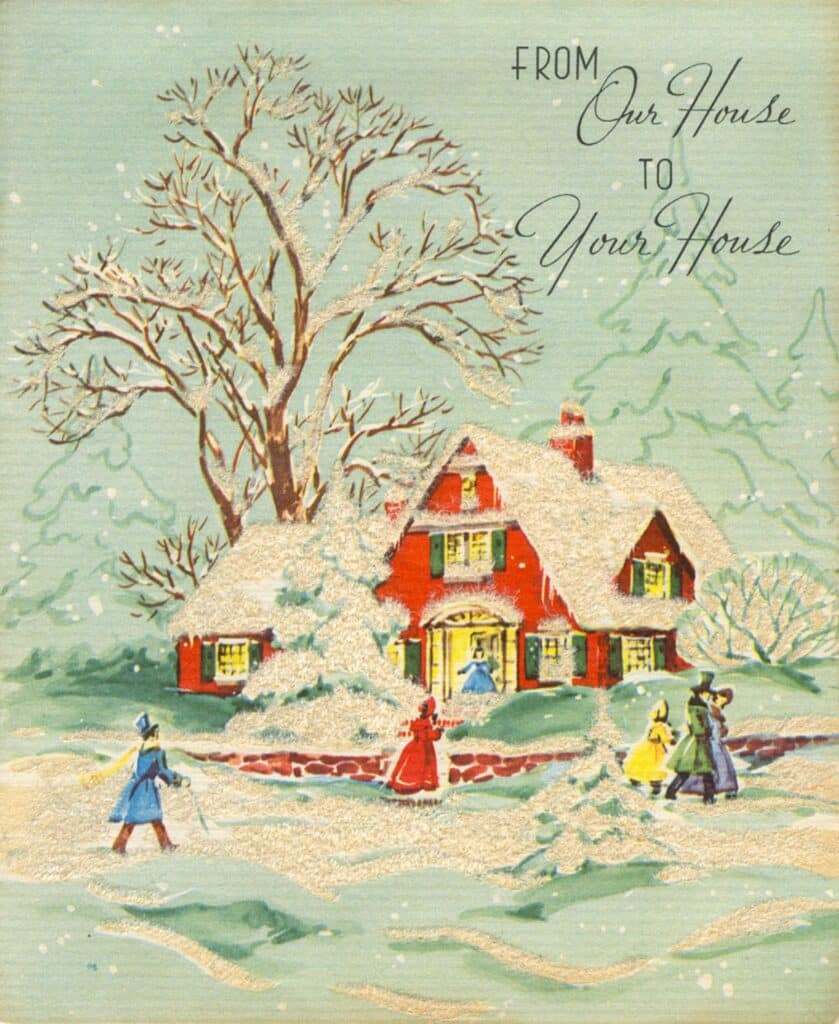

Many cards from the 1940s carry a patriotic theme, with such iconic images as the flag and eagle bearing yuletide wishes. Other recall a more peaceful time, with snow-covered villages, fresh-faced carolers, jolly Santas, and pastoral manger scenes suggesting happier days ahead. There was also a proliferation of cards dedicated to specific family members. Greetings expressly directed to “Daddy,” “A Little Daughter,” and “A Sweet Little Niece” gave Christmas cards an individual touch (and, not so coincidentally, increased card sales).

While later cards incorporated photo art, those of the 1940s and ‘50s relied mainly on illustration. Novelty additions, such as glitter, flocking, window cut-outs, pop-ups, and pull-out tabs were often used, adding to a card’s charm. Card trim could include everything from lace ribbon bows to cotton snowdrifts to metallic foil accents. And, while generic sentiments were the norm (“Here’s to luck and plenty of it! Here’s to cheer the season thru!”), various companies also employed recognized “name” talents to compose their interior messages. These ranged from the homespun (poet Edgar Guest), to the inspirational (Norman Vincent Peale).

Other top trends of the times:

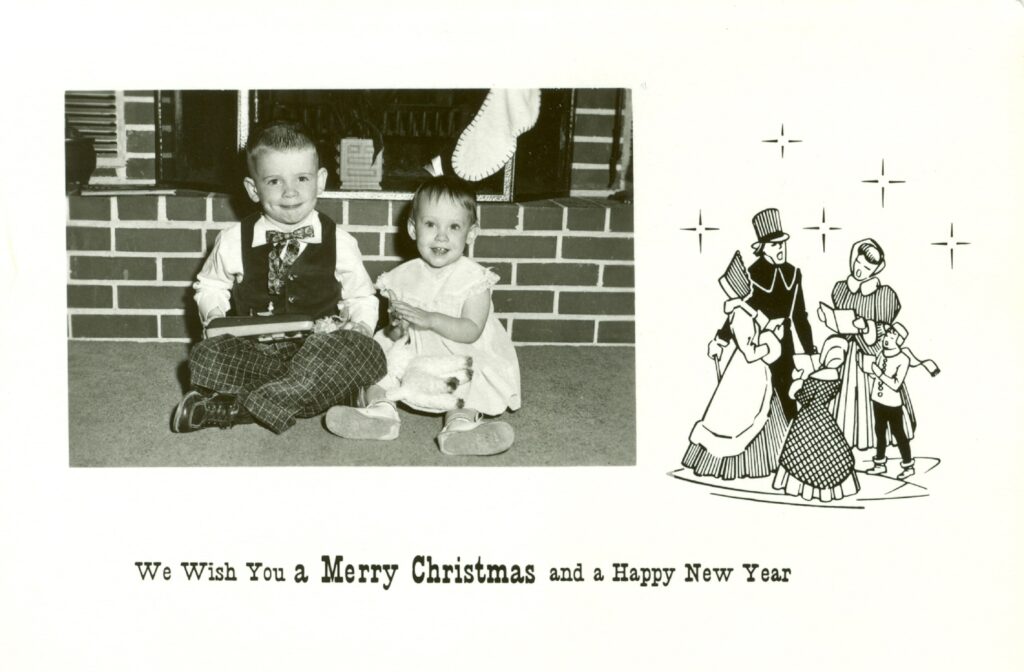

- Photo Cards. Whether it’s a selfie or a professional shot, for many folks today, a Christmas card without photos would be unthinkable. The fad actually began in the late 1930s, with amateur black-and-whites adorning semi-glossy one-sheets.

- Studio Cards. More stylized and upscale than a box of assorted holiday cards from the local dime store, the “studio card” provided understated elegance at overstated cost. First soaring to prominence in the 1950s, each season’s selection of studio cards was arranged for viewing in huge sample books, available from the various major printing firms. The more expensive cards also employed the “French fold” (the card folded in half, then folded in half again). On the mass market, cards were generally single-sided “flats.”

- Hi Brows. Instantly recognizable by their tall and narrow shape, “Hi Brows” were introduced by American Greetings in 1957. (Shortly thereafter, the style was copied by nearly everyone else.) The “Hi Brow” deconstructed the traditional Christmas greeting, reconfiguring it as hip and offbeat, with just a dash of snarky humor—perfectly attuned to the taste of young, ‘with-it’ ‘60s moderns.

In addition to American Greetings, other major card producers from the 1940s onward included Quality Cards, Artistic, Rust Craft, Norcross, Golden Bell, Stanley, and, (of course), Hallmark.

Probably the best-known name in the modern greeting card industry, Hallmark was founded by Norfolk, Nebraska native Joyce C. Hall. J.C. arrived in Kansas City in 1910, with just a shoebox full of postcards, initially conducting business out of his room at the YMCA. But Hall was a determined entrepreneur, and by 1915, “Hall Bros.” (comprised of J.C., Bill, and Rollie Hall), began to manufacture its own cards. The company, eventually relabeled “Hallmark Cards, Inc.” has been “caring enough to send the very best” ever since. (That slogan, by the way, dates from 1944; the Hallmark “crown,” developed by artist Andrew Szoerke, first appeared on cards in 1949.)

Over the decades, Christmas cards have been prized by even the most casual collectors, not only for their individual, intrinsic charm, but also for the nostalgic memories they evoke. Memories, if not of a time we personally recall, at least of a time we’ve heard about, or read about, or dreamed about. Arranged individually, in groupings, or as part of a larger holiday display, vintage Christmas cards remain an extremely affordable collectible, usually ranging from $5-10 each. They also provide an ongoing visual impetus for peace and good will, not just at Christmastime, but year-round.

Today, as in the past, the exchange of Christmas cards continues to serve its original function: bringing good cheer to those we cherish. Even more importantly, in our far-flung modern world, holiday cards help reinforce the ties of friendship and family that bind us all together. Those we care about may now be in distant spots across the country, or around the globe. Communication may be erratic the rest of the year, but a Christmas card keeps the lines of communication open and alive. It says “Now, right at this very moment, you, and you alone, are in my thoughts. Merry Christmas!”

Photo Associate: Hank Kuhlmann

Donald-Brian Johnson is the co-author of numerous Schiffer books on design and collectibles, including Postwar Pop, a collection of his columns. Please address inquiries (or Christmas greetings) to: donaldbrian@msn.com