Picture Perfect: Vogue Picture Records

Article and photos by Donald-Brian Johnson

Downbeat magazine called them “the discs that sparkle with color.” Gimbel’s trumpeted their “new and wonderful” arrival with a full-page ad in The New York Herald Tribune. Sears, Roebuck touted them as “amazing – with some of the most sensational improvements ever made in the history of phonograph records!”

The subject of all the talk? Vogue Record’s “picture records,” those illustrated musical curiosities that have retained their unique appeal for almost 80 years. Picture discs preceded Vogue, with Noel Coward, Paul Whiteman, and the cast of Music in the Air all depicted on records of the 1920s and ’30s. They’ve even continued into the present, with vinyl visuals devoted to Elvis, the Beatles, and the musical Wicked. It was Vogue Records, however, that brought picture records to the forefront.

Post-World War II Themes

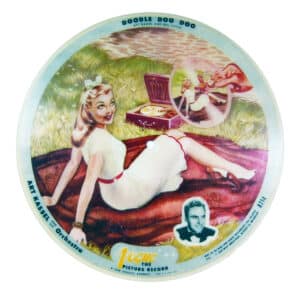

Although the company’s heyday was brief—from early 1946 through mid-1947—the Vogue titles serve as a colorful time capsule of the post-World War II era. The scenes captured could be humorous (a heavenly figure tootling a trumpet on #752, Ah Yes, There’s Good Blues Tonight), or heartrending (a black lace-clad pinup girl sobbing her heart out on #751, Mean to Me).

There was romance aplenty, from the military man and his sweetheart captured in a snowstorm embrace on #719, Have I Told You Lately That I Love You (the Scotty Wiseman song written for the 1944 film Sing, Neighbor, Sing), to the contented couple enjoying the countryside on #710, The Bells of St. Mary’s.

There were even hints of the surreal: on #748, It’s Always You, one man’s vision of loveliness looms ominously over the New York skyline, while on #730, All Through The Day, a lonesome lass peers through curtains not-so-subtly decorated with clock hands and numerals.

Although Billboard dismissed the Vogue artwork as “strictly of the coal company calendar type,” the illustrations retain a freshness and optimism totally in keeping with the spirit of postwar America.

Innovations in Record-Making Technology

Cheery artwork, however, wasn’t the guiding force behind Vogue’s creation. Like many ventures springing up after the war, an existing manufacturer was adapting wartime production facilities to new uses. Vogue’s manufacturer, Sav-Way Industries of Detroit, had spent the war years putting its patented expertise in plastic sealants to use in the creation of precision machinery. The visionary behind Vogue was Sav-Way’s president, Tom Saffady, was just 29 when record production began.

Saffady’s intent was to create an “unbreakable” record, replacing easily-shattered shellac discs. Vogue records were, in essence, a “record sandwich.” Each 10-inch 78 record had an interior aluminum core bonded to Sav-Way’s transparent Vinylite plastic. In addition to increasing durability, the aluminum core also made the records warp-proof, while the plastic reduced surface and needle noise. Up to 500 hiss-less plays per record were advertised, a major achievement in the days before noiseless CDs.

And—oh yes—there were the pictures captured under the vinyl, the delicious filling in the Vogue sandwich. These, more than anything else, set Vogue apart from run-of-the-mill recordings. The Fall/Winter 1946-47 Sears catalog noted that Sav-Way had produced “something really new in record music! Vogue’s exciting Picture Records dramatically portray each song in appropriate full-color illustrations … tell you at a glance what the music is like. . .give you finer recordings of distinctive new beauty to treasure in your record collection.”

Saffady’s Vogue project was an ambitious one, and he spared no expense in getting it underway. All production, except label printing, was centered at the Detroit plant. A Saffady-invented automatic record pressing carousel was intended to dramatically speed up record production, with discs stamped out some eighty times faster than previously. The initial goal, as Saffady told The Detroit Free Press, was “500,000 records monthly, a million soon.” There was also a complete in-house recording studio, billed as “the Midwest’s modern marvel.”

Building a Diverse Inventory

Now in full swing as a musical entrepreneur, Tom Saffady bought a Detroit nightclub so that Vogue acts could play the club – as well as cut records for his label. Stepping up to the Vogue studio bandstand were such musical luminaries of the time as Clyde McCoy, Art Mooney, Shep Fields, Art Kassel, and Enric Madriguera and their Orchestras; the Charlie Shavers Quintet; vocalists Marion Mann and “Your Hit Parade” star Joan Edwards; the King’s Jesters & Louise, and the Don Large Chorus. Country-western charmers took center stage as well: Patsy Montana, the “cowboy’s sweetheart”; Lulu Belle & Scotty; Nancy Lee & The Hilltoppers, and The Down Homers.

Novelty entries included “The Jewell Playhouse.” Performers under the direction of Richard Jewell, writer/director of radio’s The Lone Ranger and Jack Armstrong: The All-American Boy, brought to life the kiddie-pleasing Trial of Bumble the Bee and The Boy Who Cried Wolf.

There were also “learn to dance the rhumba” sets (complete with foot cutouts, and nearly-impossible-to-follow step diagrams), and several contributions by those only-in-the-1940s radio headliners, “Phil Spitalny’s Hour of Charm All-Girl Orchestra and Choir.” (#725, Alice Blue Gown, depicts Phil’s featured attraction, “Evelyn and her Magic Violin,” glamorously sawing away).

What Could Go Wrong?

With so much going for it, Saffady’s brainchild seemed destined for success. Yet, within just over a year, the vogue for Vogue was over. One reason may have been a declining interest in the big band music that had been so popular in the early 1940s. Another may have been a series of mishaps that led to delays in the record company’s debut: a late-1945 fire at the plant, just as production was getting underway, and the failure of several of Saffady’s inventions to live up to expectations (including the much-ballyhooed automated pressing carousel). Even the picture disc pictures themselves posed problems: application of the Vinylite coating over the aluminum core resulted in many ripped, and thus unusable, illustrated labels.

From January, 1946 onward, Billboard ads announced, “Vogue Records: now in production,” but the first releases didn’t hit the record racks until May. Phil Spitalny and all the “Hour of Charm” girls marked the occasion with an in-store appearance at Gimbel’s Department Store in New York – yet just as Vogue records reached the public, their downward slide began. Vogues were priced at just over a dollar (about twice the going rate for a traditional 78 record). For that price, buyers wanted more than just an illustrated, unbreakable record. They wanted a hit, the one thing Vogue was unable to supply.

While Vogue contracted with “name” artists, most of those names were not yet (or no longer, or not ever), in the top tier occupied by such in-demand performers as Frank Sinatra, Dinah Shore, and Bing Crosby. Coupled with this, most of the songs recorded by Vogue were “covers” of existing hits. It’s easy to understand the public’s lack of enthusiasm: why invest in the Vogue version, no matter how lavishly illustrated, when recordings by original artists were still readily available?

Saffady’s Legacy

Hampered by the high overhead at his production facility, Saffady sought additional financing, then potential buyers, and finally, in August, 1947, the solace of bankruptcy. Ironically, a Billboard poll, released in the fall of that year, gave Vogue discs high marks for their durability and sound reproduction quality. Plagued by ulcers, Tom Saffady outlived his company only briefly, dying at the age of 38 in 1954.

His picture discs, however, live on. Few collectors are lured by the actual recordings themselves (“does anyone,” said one, “actually play a Vogue record?”) The artwork is what draws the fans, combining elements of Hollywood glamour, pinup art, old-fashioned unabashed sentiment, and just a touch of all-American 1940s whimsy. The Vogue visual style comes courtesy of an unheralded roster of artists, some known only by their signatures: Ruth Corbett, Walter Sprink, Richard Harker, Will Wirts, M. Kanouse, and R. Forbes. Thanks to the impenetrability of the Vinylite coating, many Vogue illustrations remain just as richly and vibrantly colored as the day they came off the press.

Collectors drawn to the themes and the colors of a Vogue record also get “two for the price of one,” since each side features a different illustration. Whether framed, displayed on plate stands, or hung on a wall, the flip side of a Vogue can be easily displayed whenever the mood strikes. (Full details on all the Vogue visuals can be found online at voguepicturerecords.org).

Collecting Vogue Records

Unlike many collectibles, there’s at least a fighting chance that an avid collector might someday acquire most, if not all, of the Vogues issued. Only a finite number (approximately 75, although not all numbers were consecutive) were released in the Vogue “R700” series, and all but a handful show up regularly on auction sites. (A recent eBay search turned up 700-plus original Vogues, most selling for under $100.) For those collectors on stricter budgets, there are even recent vinyl reissues of assorted Vogue titles, courtesy of Bear Family Records. These can be distinguished from the originals by their black borders.

In 1946, as Vogue picture records took their first bow, Gimbel’s proclaimed them just right for “collectors, jitterbugs, old tune hummers, and all the other disc devotees of America.” Today, nearly 80 years after the company ceased production, the same remains true. Tom Saffady’s personal dreams—“Vogue: The Recordings with Color”—are as colorful, unforgettable, and dream-inspiring as ever.

Donald-Brian Johnson is the co-author of numerous books on design and collectibles, including Postwar Pop, a collection of his columns. A Vogue collector himself, he’s still in search of 711, 713, 715, and the ever-elusive 784. Please address inquiries to: donaldbrian@msn.com

Photo Associate: Hank Kuhlmann.