Page 36 - Layout 1

P. 36

Harvard’s Collection of Historical Scientific

Instruments and Its Founder, David P. Wheatland

Sara J. Schechner, Ph. D. (photos: Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, Harvard University)

his is a story of the impact a collector can have on creating one astronomical events during the American Revolution and surveyed

of the world’s most celebrated of specialized museums. The boundaries between the new states. Electrical machines, air pumps, and

Tmuseum is Harvard University’s Collection of Historical orreries taught natural philosophy to John Quincy Adams. In the 19th

Scientific Instruments and the man responsible is David P. Wheatland and early 20th centuries, Harvard’s scientists turned to France,

of Topsfield, Massachusetts. Germany, and eventually, the United States to outfit laboratories, the

The Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments is one of the observatory, and lecture halls. Chemicals produced in Paris for the

finest university collections of its kind in the world. It holds more than Medical College of Alabama were captured en route during the Civil

22,000 artifacts dating from the 15th century to the present and spans a War and diverted to Harvard. They sit on Harvard shelves still. Close to

broad range of disciplines, including astronomy, physics, biology, 100 train wrecks in New England before 1853—when one of the worst

chemistry, geology, meteorology, mathematics, medicine, psychology, head-on collisions at the Boston Switch was blamed on a conductor’s

navigation, horology, surveying, photography, and communications. faulty watch and his hubris that he could beat the oncoming train—led

Many of these scientific instruments were acquired by Harvard for railroad superintendents to beseech the Harvard College Observatory to

research and teaching starting in the 17th century. Others were the gifts provide time signals for the rails. The Observatory obliged by hooking

of collectors. The historical value of the instruments is greatly enhanced up its best clock to telegraph lines to tell the time. That clock by William

by original documents preserved in the Harvard University Archives and Bond & Sons still runs and is on display. These are but a few of the

by over 6,500 books and pamphlets in the collection’s research library stories told by a Collection that preserves the research apparatus of Louis

that describe the purchase and use of many of the instruments. Agassiz, Oliver Wendell Holmes, William James, Annie Jump

Cannon, Grace Hopper, and B. F. Skinner; and the pedagogical

THE FIRST GREAT INFLUENCER equipment that instructed Henry David Thoreau, W.E.B. Du Bois,

The objects in the Collection can be beautiful to gaze upon and Theodore Roosevelt, and Gertrude Stein.

reveal exquisite craftsmanship, but these tangible things are more than

relics. Not only do they trace the development of scientific activity over THE NEXT GREAT INFLUENCER

500 years, but they also exhibit the confluence of religion, politics, None of this apparatus would have been

philosophy, art, and commerce with our understanding of nature and preserved, much less assembled in one

the use of technology. Take for instance the large number of instruments place, without the stewardship of David

that Harvard purchased in London with the help of Benjamin Franklin Wheatland.

after a disastrous fire in 1764 destroyed the College’s philosophical David Pingree Wheatland (1898-

apparatus. Franklin was in London on political business but offered to 1993)—known affectionately to many as

be Harvard’s “personal shopper.” He must have had a ball going to his Mr. Wheatland—began amassing the

favorite instrument makers and spending Harvard’s money. He bought nucleus of objects that were to become the

better quality than he could afford Collection of Historical Scientific

for himself. Consequently, Harvard Instruments in the 1920s. After graduating

now has more apparatus associated David P. Wheatland from Harvard College in 1922 with a

with Franklin than survives in Bachelor of Science degree, he became

Philadelphia. involved in his family’s lumber business in Maine. Though successful in

Franklin’s instruments have their business, he remained unfulfilled in this work, and Mr. Wheatland

own stories to tell. Clocks, quadrants, returned to Harvard in 1928 to work in the Physics Department, first as

and telescopes were taken behind a technical assistant to Professor Leon Chaffee, then as Department

British enemy lines to observe rare Secretary, and in 1940, as the Assistant Director of the Cruft Research

Laboratory of Physics. In the latter position, he oversaw the assembly

of the first programmable computer in the United States, the

IBM-Harvard Mark I, and became one of its first civilian operators.

Mr. Wheatland’s duties in the Physics Department led to numerous

encounters with obsolete instrumentation often discarded in the

stairwells and attics of the science buildings on campus. A zealous

collector of rare books on electricity and magnetism, Mr. Wheatland

recognized what these castoff instruments were from the marvelous

engravings in his old books. He understood that these objects represented

an important part of the local scientific heritage, but he feared that they

were in physical danger due to neglect as well as the propensity of faculty

and students to cannibalize them for spare parts. Since the Physics

Department did not then see any value in the instruments, Mr.

Wheatland took them into his office for safekeeping. Larger items, like

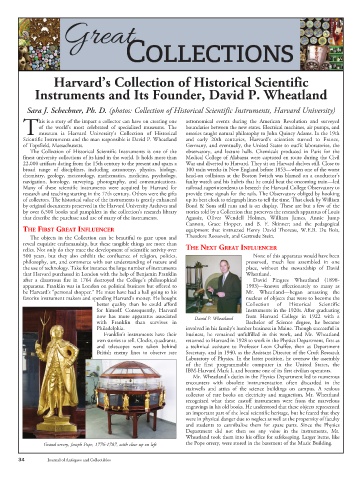

Grand orrery, Joseph Pope, 1776-1787, with close up on left the Pope orrery, were stored in the basement of the Music Building.

34 Journal of Antiques and Collectibles