Page 26 - JOA-Oct-21

P. 26

The Dugan property in 1827 included a house, barn, and seven acres

of land valued at $300. A cow appraised at $12 was Dugan’s most valuable

piece of personal property. Dugan’s seven acres was only enough land to

supply his cow with grazing feed in the summer and cut hay in the winter.

He used a dung fork, hoe, and shovel to accomplish tasks like moving

manure around the farmyard, weeding, and digging.

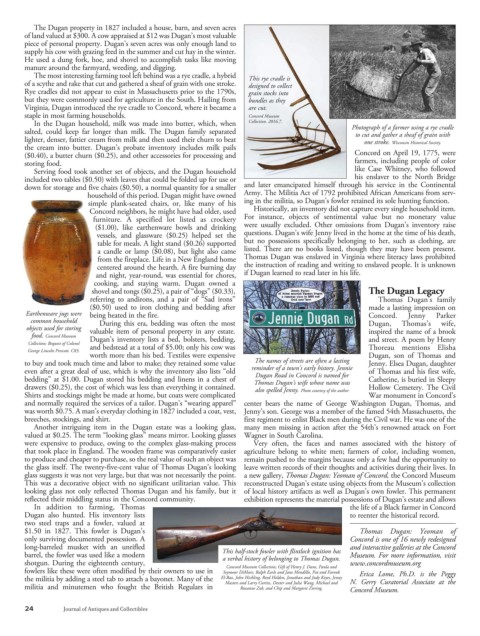

The most interesting farming tool left behind was a rye cradle, a hybrid This rye cradle is

of a scythe and rake that cut and gathered a sheaf of grain with one stroke. designed to collect

Rye cradles did not appear to exist in Massachusetts prior to the 1790s, grain stocks into

but they were commonly used for agriculture in the South. Hailing from bundles as they

Virginia, Dugan introduced the rye cradle to Concord, where it became a are cut.

staple in most farming households. Concord Museum

In the Dugan household, milk was made into butter, which, when Collection. 2016.7.

salted, could keep far longer than milk. The Dugan family separated Photograph of a farmer using a rye cradle

to cut and gather a sheaf of grain with

lighter, denser, fattier cream from milk and then used their churn to beat

one stroke. Wisconsin Historical Society.

the cream into butter. Dugan’s probate inventory includes milk pails

($0.40), a butter churn ($0.25), and other accessories for processing and Concord on April 19, 1775, were

storing food. farmers, including people of color

Serving food took another set of objects, and the Dugan household like Case Whitney, who followed

included two tables ($0.50) with leaves that could be folded up for use or his enslaver to the North Bridge

down for storage and five chairs ($0.50), a normal quantity for a smaller and later emancipated himself through his service in the Continental

household of this period. Dugan might have owned Army. The Militia Act of 1792 prohibited African Americans from serv-

simple plank-seated chairs, or, like many of his ing in the militia, so Dugan’s fowler retained its sole hunting function.

Concord neighbors, he might have had older, used Historically, an inventory did not capture every single household item.

furniture. A specified lot listed as crockery For instance, objects of sentimental value but no monetary value

($1.00), like earthenware bowls and drinking were usually excluded. Other omissions from Dugan’s inventory raise

vessels, and glassware ($0.25) helped set the questions. Dugan’s wife Jenny lived in the home at the time of his death,

table for meals. A light stand ($0.26) supported but no possessions specifically belonging to her, such as clothing, are

a candle or lamp ($0.08), but light also came listed. There are no books listed, though they may have been present.

from the fireplace. Life in a New England home Thomas Dugan was enslaved in Virginia where literacy laws prohibited

centered around the hearth. A fire burning day the instruction of reading and writing to enslaved people. It is unknown

and night, year-round, was essential for chores, if Dugan learned to read later in his life.

cooking, and staying warm. Dugan owned a

shovel and tongs ($0.25), a pair of “dogs” ($0.33), The Dugan Legacy

referring to andirons, and a pair of “Sad irons” Thomas Dugan’s family

($0.50) used to iron clothing and bedding after made a lasting impression on

Earthenware jugs were being heated in the fire. Concord. Jenny Parker

common household During this era, bedding was often the most Dugan, Thomas’s wife,

objects used for storing

valuable item of personal property in any estate. inspired the name of a brook

food. Concord Museum

Dugan’s inventory lists a bed, bolsters, bedding, and street. A poem by Henry

Collection; Bequest of Colonel

and bedstead at a total of $5.00; only his cow was Thoreau mentions Elisha

George Lincoln Prescott. C85.

worth more than his bed. Textiles were expensive Dugan, son of Thomas and

to buy and took much time and labor to make; they retained some value The names of streets are often a lasting Jenny. Elsea Dugan, daughter

even after a great deal of use, which is why the inventory also lists “old reminder of a town’s early history. Jennie of Thomas and his first wife,

Dugan Road in Concord is named for

bedding” at $1.00. Dugan stored his bedding and linens in a chest of Thomas Dugan’s wife whose name was Catherine, is buried in Sleepy

drawers ($0.25), the cost of which was less than everything it contained. Hollow Cemetery. The Civil

also spelled Jenny. Photo courtesy of the author

Shirts and stockings might be made at home, but coats were complicated War monument in Concord’s

and normally required the services of a tailor. Dugan’s “wearing apparel” center bears the name of George Washington Dugan, Thomas, and

was worth $0.75. A man’s everyday clothing in 1827 included a coat, vest, Jenny’s son. George was a member of the famed 54th Massachusetts, the

breeches, stockings, and shirt. first regiment to enlist Black men during the Civil war. He was one of the

Another intriguing item in the Dugan estate was a looking glass, many men missing in action after the 54th’s renowned attack on Fort

valued at $0.25. The term “looking glass” means mirror. Looking glasses Wagner in South Carolina.

were expensive to produce, owing to the complex glass-making process Very often, the faces and names associated with the history of

that took place in England. The wooden frame was comparatively easier agriculture belong to white men; farmers of color, including women,

to produce and cheaper to purchase, so the real value of such an object was remain pushed to the margins because only a few had the opportunity to

the glass itself. The twenty-five-cent value of Thomas Dugan’s looking leave written records of their thoughts and activities during their lives. In

glass suggests it was not very large, but that was not necessarily the point. a new gallery, Thomas Dugan: Yeoman of Concord, the Concord Museum

This was a decorative object with no significant utilitarian value. This reconstructed Dugan’s estate using objects from the Museum’s collection

looking glass not only reflected Thomas Dugan and his family, but it of local history artifacts as well as Dugan’s own fowler. This permanent

reflected their middling status in the Concord community. exhibition represents the material possessions of Dugan’s estate and allows

In addition to farming, Thomas the life of a Black farmer in Concord

Dugan also hunted. His inventory lists to reenter the historical record.

two steel traps and a fowler, valued at

$1.50 in 1827. This fowler is Dugan’s Thomas Dugan: Yeoman of

only surviving documented possession. A Concord is one of 16 newly redesigned

long-barreled musket with an unrifled and interactive galleries at the Concord

barrel, the fowler was used like a modern This half-stock fowler with flintlock ignition has Museum. For more information, visit

a verbal history of belonging to Thomas Dugan.

shotgun. During the eighteenth century, www.concordmuseum.org

Concord Museum Collection; Gift of Henry J. Dane, Paula and

fowlers like these were often modified by their owners to use in Seymour DiMare, Ralph Earle and Jane Mendillo, Pat and Farouk Erica Lome, Ph.D. is the Peggy

the militia by adding a steel tab to attach a bayonet. Many of the El-Baz, John Hickling, Reed Holden, Jonathan and Judy Keyes, Jenny

Masters and Larry Curtiss, Dexter and Julia Wang, Michael and N. Gerry Curatorial Associate at the

militia and minutemen who fought the British Regulars in Roxanne Zak, and Chip and Margaret Ziering. Concord Museum.

24 Journal of Antiques and Collectibles