Page 21 - JOA-2-22

P. 21

smooth, and seams stitched by apprentices strong, for an overall correct name was Jemmy, wore leather breeches in addition to a dark frieze

“look” to many different kinds of finished garments. While master jacket and leather heeled shoes. Middletown, Connecticut, tailor

tailors and their journeymen usually performed the more skilled and Jehosaphat Starr, who could count among his customers young

specialized tasks in a shop, such as measuring clients, and arranging the Jeremiah Wadsworth, also made at least three pairs of leather breeches

pattern pieces of a garment onto the fabric, and cutting them out, less for enslaved men, along with making or altering vests and coats, in the

17

skilled labor including enslaved men and white apprentices heated third quarter of the 18th century.

irons, stocked the shop and maintained its working order, performed

errands, and delivered goods. Less skilled sewing work could include Conclusion

the repetitive stitching to secure seams on rectilinear pattern pieces Exeter, the man cited

making up garments such as shirts or trousers [Figure 2]. at the beginning of this

Documentation of the specific skills of enslaved men in the trade is article, was in fact one of

scarce. An unnamed enslaved man, “very fit for a Taylor,” was recorded four enslaved men

as possessing the knowledge to “work in Leather very well, having been collectively held captive

used to the Needle for above a Dozen Years.” No evidence has come to by the partnership of

light regarding enslaved men reaching the equivalent of master tailor John and Richard

status. In all likelihood, they never did so in any official capacity, for Billings. These four men

reasons including suppression by competing white members of the were all listed among the

profession, as well as a lack of opportunity. Through years of unpaid property and real estate

12

work, however, some enslaved men may have reached an equivalent at the time of the disso-

competency in the trade. The sale of the “Likely, healthy Negro Fellow” lution of the brothers’

who “work’d at the Taylor’s Trade seven years” suggests the unnamed business in 1763. The

enslaved man clocked the same amount of time that a white apprentice first names of all four

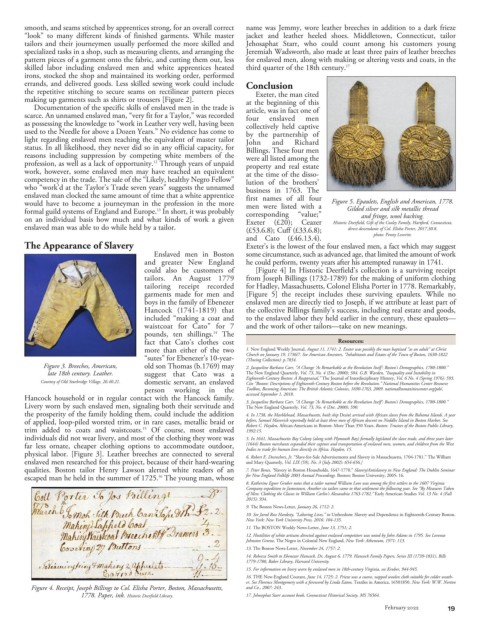

would have to become a journeyman in the profession in the more men were listed with a Figure 5. Epaulets, English and American, 1778.

formal guild systems of England and Europe. In short, it was probably corresponding “value;” Gilded silver and silk metallic thread

13

and fringe, wool backing.

on an individual basis how much and what kinds of work a given Exeter (£20); Ceazer Historic Deerfield, Gift of the Cooley Family, Hartford, Connecticut,

enslaved man was able to do while held by a tailor. direct descendants of Col. Elisha Porter, 2017.30.8.

(£53.6.8); Cuff (£33.6.8);

and Cato (£46.13.4). photo: Penny Leveritt.

The Appearance of Slavery Exeter’s is the lowest of the four enslaved men, a fact which may suggest

Enslaved men in Boston some circumstance, such as advanced age, that limited the amount of work

and greater New England he could perform, twenty years after his attempted runaway in 1741.

could also be customers of [Figure 4] In Historic Deerfield’s collection is a surviving receipt

tailors. An August 1779 from Joseph Billings (1732-1789) for the making of uniform clothing

tailoring receipt recorded for Hadley, Massachusetts, Colonel Elisha Porter in 1778. Remarkably,

garments made for men and [Figure 5] the receipt includes these surviving epaulets. While no

boys in the family of Ebenezer enslaved men are directly tied to Joseph, if we attribute at least part of

Hancock (1741-1819) that the collective Billings family’s success, including real estate and goods,

included “making a coat and to the enslaved labor they held earlier in the century, these epaulets—

waistcoat for Cato” for 7 and the work of other tailors—take on new meanings.

pounds, ten shillings. The

14

fact that Cato’s clothes cost Resources:

more than either of the two 1. New England Weekly Journal, August 11, 1741: 2. Exeter was possibly the man baptized “as an adult” at Christ

“sutes” for Ebenezer’s 10-year- Church on January 19, 1736/7. See American Ancestors, “Inhabitants and Estates of the Town of Boston, 1630-1822

(Thwing Collection): p.7834.

Figure 3. Breeches, American, old son Thomas (b.1769) may 2. Jacqueline Barbara Carr, “A Change ‘As Remarkable as the Revolution Itself’: Boston’s Demographics, 1780-1800.”

late 18th century. Leather. suggest that Cato was a The New England Quarterly, Vol. 73, No. 4 (Dec. 2000); 584. G.B. Warden, “Inequality and Instability in

Courtesy of Old Sturbridge Village, 26.40.21. domestic servant, an enslaved Eighteenth-Century Boston: A Reappraisal,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 6 No. 4 (Spring 1976): 593.

Cite “Boston: Descriptions of Eighteenth-Century Boston before the Revolution.” National Humanities Center Resource

person working in the Toolbox, Becoming American: The British Atlantic Colonies, 1690-1763, 2009. nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/,

Hancock household or in regular contact with the Hancock family. accessed September 1, 2018.

3. Jacqueline Barbara Carr, “A Change ‘As Remarkable as the Revolution Itself’: Boston’s Demographics, 1780-1800.”

Livery worn by such enslaved men, signaling both their servitude and The New England Quarterly, Vol. 73, No. 4 (Dec. 2000); 590.

the prosperity of the family holding them, could include the addition 4. In 1738, the Marblehead, Massachusetts, built ship Desiré arrived with African slaves from the Bahama Islands. A year

of applied, loop-piled worsted trim, or in rare cases, metallic braid or before, Samuel Maverick reportedly held at least three men of African descent on Noddles Island in Boston Harbor. See

Robert C. Hayden, African-Americans in Boston: More Than 350 Years. Boston: Trustees of the Boston Public Library,

trim added to coats and waistcoats. Of course, most enslaved 1992:15.

15

individuals did not wear livery, and most of the clothing they wore was 5. In 1641, Massachusetts Bay Colony (along with Plymouth Bay) formally legislated the slave trade, and three years later

far less ornate, cheaper clothing options to accommodate outdoor, (1644) Boston merchants expanded their capture and transportation of enslaved men, women, and children from the West

Indies to trade for human lives directly in Africa. Hayden, 15.

physical labor. [Figure 3]. Leather breeches are connected to several 6. Robert E. Desrochers, Jr. “Slave-for-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704-1781.” The William

enslaved men researched for this project, because of their hard-wearing and Mary Quarterly, Vol. LIX (59), No. 3 (July 2002): 654-656.]

qualities. Boston tailor Henry Lawson alerted white readers of an 7. Peter Benes, “Slavery in Boston Households, 1647-1770.” Slavery/Antislavery in New England: The Dublin Seminar

escaped man he held in the summer of 1725. The young man, whose for New England Folklife 2003 Annual Proceedings. Boston: Boston University, 2005: 16.

16

8. Katherine Egner Gruber notes that a tailor named William Love was among the first settlers to the 1607 Virginia

Company expedition to Jamestown. Another six tailors came to that settlement the following year. See “By Measures Taken

of Men: Clothing the Classes in William Carlin’s Alexandria 1763-1782.” Early American Studies Vol. 13 No. 4 (Fall

2015): 934.

9. The Boston News-Letter, January 26, 1712: 2.

10. See Jared Ross Hardesty, “Laboring Lives,” in Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston.

New York: New York University Press, 2016: 104-135.

11. The BOSTON Weekly News-Letter, June 13, 1751; 2.

12. Hostilities of white artisans directed against enslaved competitors was noted by John Adams in 1795. See Lorenzo

Johnston Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England, New York: Atheneum, 1971: 113.

13. The Boston News-Letter, November 24, 1757: 2.

14. Rebecca Smith to Ebenezer Hancock, Dr, August 6, 1779. Hancock Family Papers, Series III (1739-1831), Bills

1779-1780, Baker Library, Harvard University.

15. For information on livery worn by enslaved men in 18th-century Virginia, see Kruber, 944-945.

16. THE New-England Courant, June 14, 1725: 2. Frieze was a coarse, napped woolen cloth suitable for colder weath-

er. See Florence Montgomery with a foreword by Linda Eaton, Textiles in America, 16501850. New York: W.W. Norton

Figure 4. Receipt, Joseph Billings to Col. Elisha Porter, Boston, Massachusetts, and Co., 2007: 243.

1778. Paper, ink. Historic Deerfield Library. 17. Jehosephat Starr account book, Connecticut Historical Society, MS 76564.

February 2022 19