Page 31 - March 2022

P. 31

County, Virginia home—to inspect his new threshing machine. In the pre-Revolution Chesapeake, livestock was more apt to be

Jefferson was impressed, although his writing after his visit reveals that free-ranging or housed in rough structures or sheds than in a barn. The

he already had plans to modify the design for his own machine. exception to that was horses. Whether for draft or recreation, horses

The barn that Jefferson visited is still standing and is now part of were kept in specialized stables. Stables ranged from commercial

Clover Hill plantation. Although modified over time, it still retains its endeavors associated with taverns or courthouses to specialized buildings

18th-century appearance. Like its Pennsylvania bank barn cousins to the for specific horse types where draft horses, carriage horses, and

north, this barn is built into a small hill. Livestock pens on the cellar level racehorses were segregated due to their specific needs. In urban

provided animal shelter, while the first floor opened to a large threshing environments, small one- to four-stall stables often sat at the rear of the

floor. Substantial posts with decorative chamfers and lamb’s tongue stops lot. Whether frame, log or brick, these standing stalls were about four

provide a modicum of ornamentation while functionally supporting the to five feet wide and eight to ten feet long with wooden partitions.

second-floor level where hay might have been stored. Shed additions, Mangers for grain and feed bins were part of most stable furnishings.

built between 1800-1805 acted as a granary, allowing the entire process Tack and equipment were kept on racks and pegs nearby. Ventilation

of wheat production and storage to occur in one building. and drainage were important factors in situating and siting a stable.

Today, the Department of Architectural Preservation and Research

Corn Cribs at Colonial Williamsburg is actively researching colonial stables in an

effort to reconstruct Peyton Randolph’s stable, which was demolished

sometime in the 19th century. The building was listed as “stables to

hold twelve horses and room for two carriages” in the 1783 auction of

the property following Betty Randolph’s death. Once completed, this

stable will be home to Colonial Williamsburg’s rare breeds program

and will provide a much-needed space to showcase the many heirloom

animal varieties that Colonial Williamsburg maintains.

Livestock Houses

Throughout much

of the 18th century,

housing for livestock

was basic, or non-exis-

tent. Hogs, cattle, and

sheep could free-range

until slaughter or sale.

However, towards the

end of the 18th century,

housing for cattle and

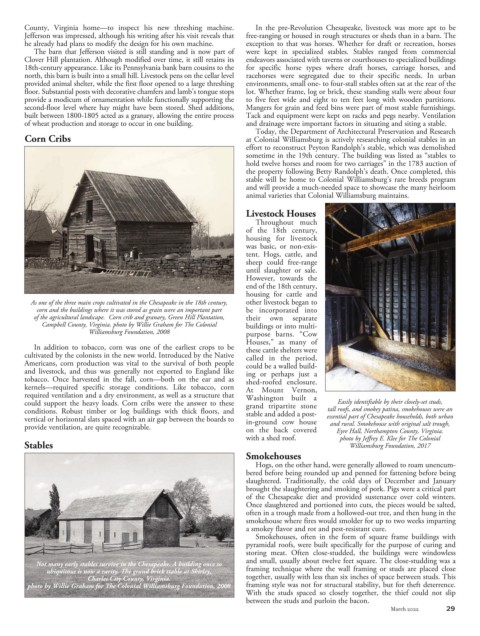

As one of the three main crops cultivated in the Chesapeake in the 18th century, other livestock began to

corn and the buildings where it was stored as grain were an important part be incorporated into

of the agricultural landscape. Corn crib and granary, Green Hill Plantation, their own separate

Campbell County, Virginia. photo by Willie Graham for The Colonial buildings or into multi-

Williamsburg Foundation, 2008 purpose barns. “Cow

Houses,” as many of

In addition to tobacco, corn was one of the earliest crops to be these cattle shelters were

cultivated by the colonists in the new world. Introduced by the Native called in the period,

Americans, corn production was vital to the survival of both people could be a walled build-

and livestock, and thus was generally not exported to England like ing or perhaps just a

tobacco. Once harvested in the fall, corn—both on the ear and as shed-roofed enclosure.

kernels—required specific storage conditions. Like tobacco, corn At Mount Vernon,

required ventilation and a dry environment, as well as a structure that Washington built a

could support the heavy loads. Corn cribs were the answer to these grand tripartite stone Easily identifiable by their closely-set studs,

conditions. Robust timber or log buildings with thick floors, and stable and added a post- tall roofs, and smokey patina, smokehouses were an

vertical or horizontal slats spaced with an air gap between the boards to in-ground cow house essential part of Chesapeake households, both urban

provide ventilation, are quite recognizable. and rural. Smokehouse with original salt trough,

on the back covered Eyre Hall, Northampton County, Virginia.

with a shed roof. photo by Jeffrey E. Klee for The Colonial

Stables Williamsburg Foundation, 2017

Smokehouses

Hogs, on the other hand, were generally allowed to roam unencum-

bered before being rounded up and penned for fattening before being

slaughtered. Traditionally, the cold days of December and January

brought the slaughtering and smoking of pork. Pigs were a critical part

of the Chesapeake diet and provided sustenance over cold winters.

Once slaughtered and portioned into cuts, the pieces would be salted,

often in a trough made from a hollowed-out tree, and then hung in the

smokehouse where fires would smolder for up to two weeks imparting

a smokey flavor and rot and pest-resistant cure.

Smokehouses, often in the form of square frame buildings with

pyramidal roofs, were built specifically for the purpose of curing and

storing meat. Often close-studded, the buildings were windowless

and small, usually about twelve feet square. The close-studding was a

Not many early stables survive in the Chesapeake. A building once so

ubiquitous is now a rarity. The grand brick stable at Shirley, framing technique where the wall framing or studs are placed close

Charles City County, Virginia. together, usually with less than six inches of space between studs. This

photo by Willie Graham for The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2008 framing style was not for structural stability, but for theft deterrence.

With the studs spaced so closely together, the thief could not slip

between the studs and purloin the bacon.

March 2022 29