A Museum of the Mind: Dataland

In late 2025, an unprecedented art center will open in Los Angeles: Dataland, the world’s first museum dedicated to AI-generated art. Turkish-American artist Refik Anadol will lead the center. He is a leading global figure at the intersection of machine intelligence, immersive environments, and new media art.

If art museums are traditionally the keepers of human culture, Dataland asks us to consider a new question: What happens when the act of creation is shared with or handed over to a machine?

Reifik Anadol: A New Imagination

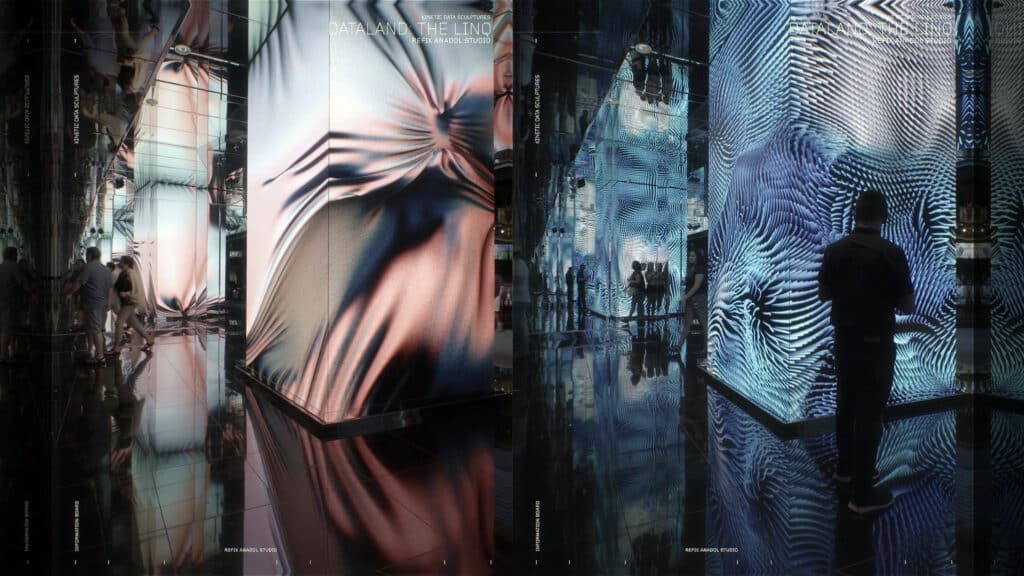

Refik Anadol is no stranger to breaking boundaries. Over the past decade, he has gained recognition for his large-scale public art installations, which utilize algorithms, datasets, and machine-learning models as materials and collaborators. Whether projecting undulating, AI-generated visuals onto the façades of buildings like the Walt Disney Concert Hall or turning EEG brainwave data into immersive room-sized light sculptures, Anadol has persistently challenged assumptions about creativity, agency, and perception.

Anadol does not simply use AI as a tool – he allows it to dream. Using generative adversarial networks (GANs), reinforcement learning, and other machine learning techniques, Anadol trains algorithms on vast data repositories, encompassing everything from meteorological recordings to images of historic artworks and neurological patterns from human subjects. The outputs are a blend of human sensibility and algorithmic interpretation that feels like watching consciousness born in real-time.

With Dataland, Anadol is institutionalizing this practice. Dataland is a museum, suggesting permanence, stewardship, and a curatorial mandate to preserve and explore a newly emerging aesthetic domain.

Why AI Art Needs a Museum

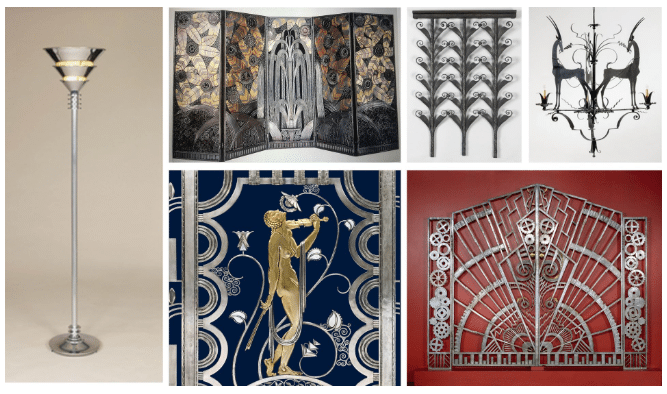

AI-generated art refers to works created collaboratively with artificial intelligence or entirely produced by machine learning models. Unlike traditional digital art, which is often made with computers, AI art typically involves training algorithms on massive datasets and allowing those systems to generate entirely new visual, sonic, or textual compositions.

The genre has grown dramatically in recent years, fueled by advances in generative models like OpenAI’s DALL·E and GPT systems, Google DeepMind’s Deep Dream, and others. Works like Mario Klingemann’s neural network portraits or Anna Ridler’s data-driven installations sit alongside Anadol’s in pushing the boundaries of authorship and aesthetics. In 2018, an AI-generated painting titled Portrait of Edmond de Belamy sold at Christie’s for over $400,000, sparking heated debates about value, originality, and the nature of artistic labor.

Therefore, Anadol’s decision to create a museum dedicated to AI art is timely. While AI-generated works have been featured in galleries and museums, including MoMA and LACMA, they have typically been presented as novelties or provocations. Dataland shifts the context entirely. It asserts that AI art is not a passing trend or conceptual stunt – it is a serious, evolving movement worthy of its own canon, institutional infrastructure, and public dialogue.

Inside Dataland: A Machine’s Eye View of the Sublime

What will Dataland look like?

According to early reports, it will not adhere to the conventional white-cube format of traditional museums. Instead, it is envisioned as an immersive, multi-sensory environment where AI-generated visuals, soundscapes, and spatial designs coalesce to create new experience forms.

Visitors may not simply view art – they may walk through it, interact with it, or perhaps be affected by it. Anadol has hinted that biometric data, emotional responses, and brain activity might be integrated into future exhibits, enabling the museum to evolve based on real-time audience behavior.

In this sense, Dataland is more than a museum – it is a platform, a research space, and a place to encounter artwork. It represents what media theorist Lev Manovich calls “cultural analytics:” the fusion of computation, data science, and aesthetics culminating in new ways of understanding art and the human mind.

Anadol’s previous work with datasets from NASA, the LA Philharmonic, and even brain scans of Alzheimer’s patients point to a deep curiosity about perception, memory, and what he calls “data pigments” – the raw material of a new kind of digital sublime.

The Critique: Can Machines Be Creative?

Not everyone is ready to welcome this new paradigm. Critics have raised important questions about whether AI art can be considered creative. After all, algorithms do not have intention, emotion, or lived experience. They remix and interpolate, but can they innovate in the human sense? Can they express joy, grief, or protest?

Philosopher Margaret Boden defines creativity as the ability to produce novel, surprising, and valuable ideas. By that measure, some AI-generated works may qualify. However, others are concerned about the implications of outsourcing aesthetic judgment and artistic production to machines. Does it devalue human creativity? Will data scientists replace artists? Or, more pressingly, will we begin to accept machine output as aesthetically sufficient without grappling with its social and ethical contexts?

Anadol’s answer seems to be collaboration rather than competition. He emphasizes that AI is not replacing the artist but expanding her toolkit. In this view, AI is like the invention of photography, or the rise of abstract expressionism—disruptive, yes, but also generative of new forms. The artist becomes not a maker, but a curator of potentialities, someone who shapes the conditions under which machine intelligence can explore aesthetic space.

Toward a New Aesthetic Epoch

Paradigm shifts punctuate art history. The Renaissance elevated human perspective; modernism shattered form; and digital art introduces interactivity and virtuality. AI art may well represent the next such era. It redefines authorship.

Dataland arrives at a crucial cultural moment, when society is grappling with the role of AI in everything from education and labor to ethics and identity. As such, it is not just a site for seeing beautiful things. It is a space for asking hard questions. What does it mean to create in the age of computation? Who owns the outputs of a neural network? Can an algorithm ever have style – or soul?

In true Anadol fashion, Dataland may not offer definitive answers. However, it will provide something just as vital: the chance to wonder and think in new ways about the ancient impulse to create meaning through images.

And that, ultimately, is the most human gesture of all.

Selected References

• Boden, M. A. (2004). The Creative Mind: Myths and Mechanisms. Routledge.

• McCormack, J., Gifford, T., & Hutchings, P. (2019). Autonomy, Authenticity, Authorship and Intention in Computer Generated Art. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Creativity and Cognition.

• Manovich, L. (2020). Cultural Analytics. MIT Press.

• Elgammal, A. et al. (2017). CAN: Creative Adversarial Networks, Generating “Art” by Learning About Styles and Deviating from Style Norms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.07068.

• Christie’s (2018). Is artificial intelligence set to become art’s next medium? Retrieved from https://www.christies.com

• Mueller, Shirley M. (2025). Auctioning AI: Ai-Da’s Historic Million-Dollar Moment, Psychology Today, April 17.

Shirley M. Mueller, M.D., is known for her expertise in Chinese export porcelain and neuroscience. Her unique knowledge in these two areas motivated her to explore the neuropsychological aspects of collecting, both to help herself and others as well. This guided her to write her landmark book, Inside the Head of a Collector: Neuropsychological Forces at Play. In it, she uses the new field of neuropsychology to explain the often-enigmatic behavior of collectors. Shirley is also a well-known speaker. She has shared her insights in London, Paris, Shanghai, and other major cities worldwide as well as across the United States. In these lectures, she blends art and science to unravel the mysteries of the collector’s mind.