Curating the Unexpected: The Joy of Flawed Chinese Export Porcelain

by Shirley M. Mueller, M.D.

“Look at me,” the large, not-to-be-missed porcelain cried out.

And I did.

It was not unlike the way cats meow at me in an animal shelter or the way dogs bark insistently until my eyes finally meet theirs. This massive porcelain punch bowl, made for the English market in 1744, had the same insistence. It wasn’t simply sitting there. It was demanding my attention, not just anyone’s, but mine.

At first, I was struck by its size, the kind of presence that feels larger than life. But then I saw it: a curious inscription. Between the a and the s of the word Haslingfield, an e was inserted, awkwardly, almost like a superscript. More accurately, the name had been misspelled first, and the tiny ‘e’ was added later to correct it.

That error electrified me. It was unexpected, unorthodox, and above all, novel. I didn’t know it then, but neuroscientists have since discovered what my brain already felt: the so-called novelty center lights up when confronted with the oddball, the unusual, the mistake that shouldn’t be there. The corrected inscription jolted me. It wasn’t just a bowl anymore. It was a discovery.

That day changed me. I began to search, not just for Chinese export porcelain (made in China but exported to the West), but for mistakes on it. For example, slips of the brush, translation errors, moments when cultures collided and produced something imperfect, yet more right for me than perfection ever could be.

And I wasn’t alone. Among collectors, it’s the errors that many gravitate toward most eagerly. These objects tell better stories than the flawless ones. They reveal the process of communication and miscommunication—across oceans and centuries.

The Puzzle Jug That Didn’t Work

One of my favorite examples of such cultural misunderstanding involves a late seventeenth-century Dutch Delft puzzle jug. In the Netherlands, the vessel was meant to trick and entertain. Liquid would only pour through the spout if it were cleverly plugged in the right sequence of holes with fingers. A game, a puzzle, and a jug all in one.

The Puzzle Jug That Didn’t Work – The object was beautiful, but dysfunctional.

The dummy holes were carefully drilled into the neck, but the crucial opening at the base of the handle—the one that made the siphon work—was left out.

When Chinese artisans around 1700 copied the form in porcelain for export, they completely missed the point. The dummy holes were carefully drilled into the neck, but the crucial opening at the base of the handle—the one that made the siphon work—was left out. The result? No liquid would pour, no matter what the drinker tried. The object was beautiful, but dysfunctional.

Here, the joke wasn’t on the guest struggling to solve the puzzle, but on the European patron who had ordered the jug. The misunderstanding turned the cleverest drinking game into a dead end. And yet, as a collector, I see in it not failure but fascination: the way one culture’s playfulness became another culture’s puzzle of a different kind.

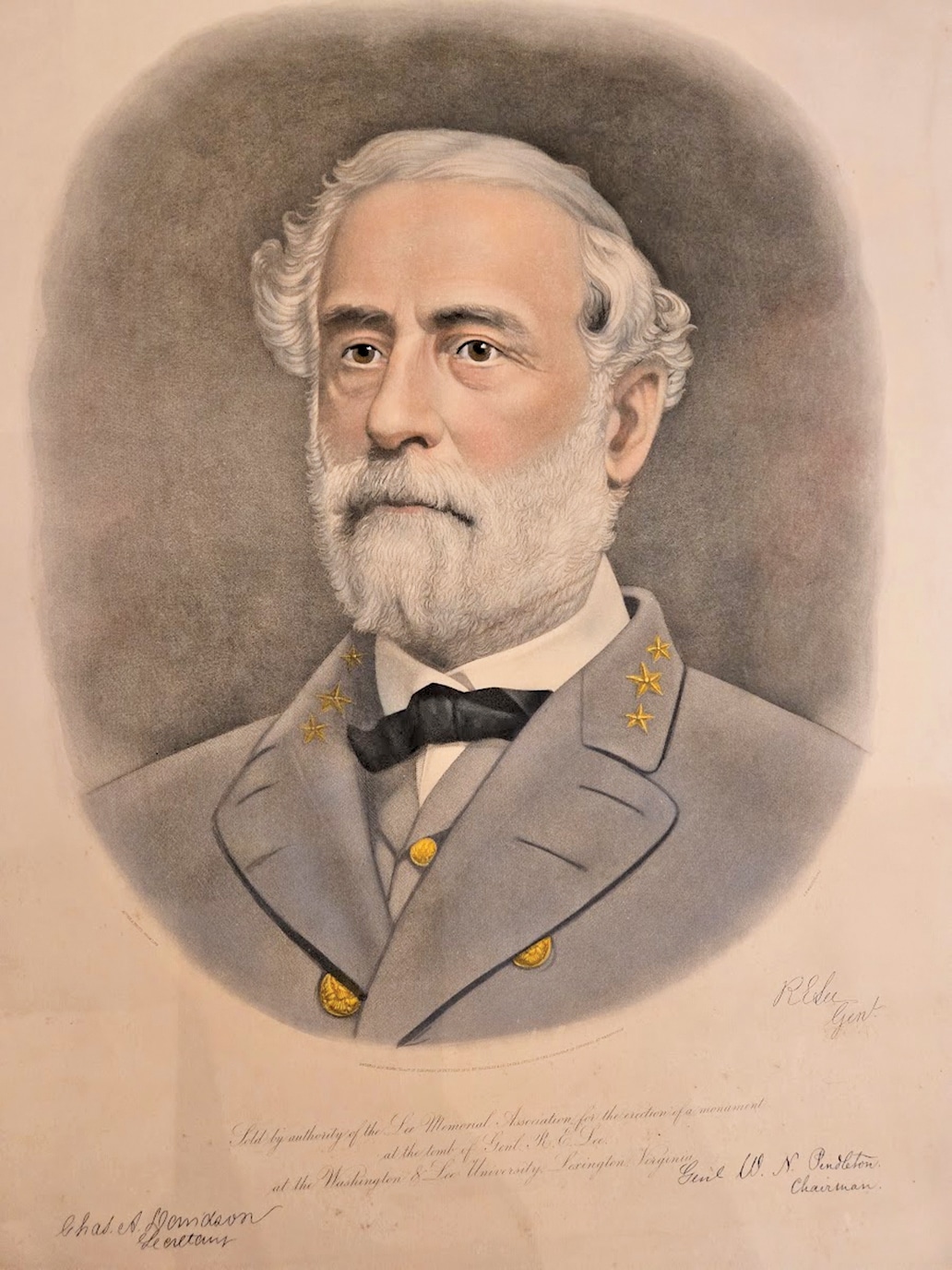

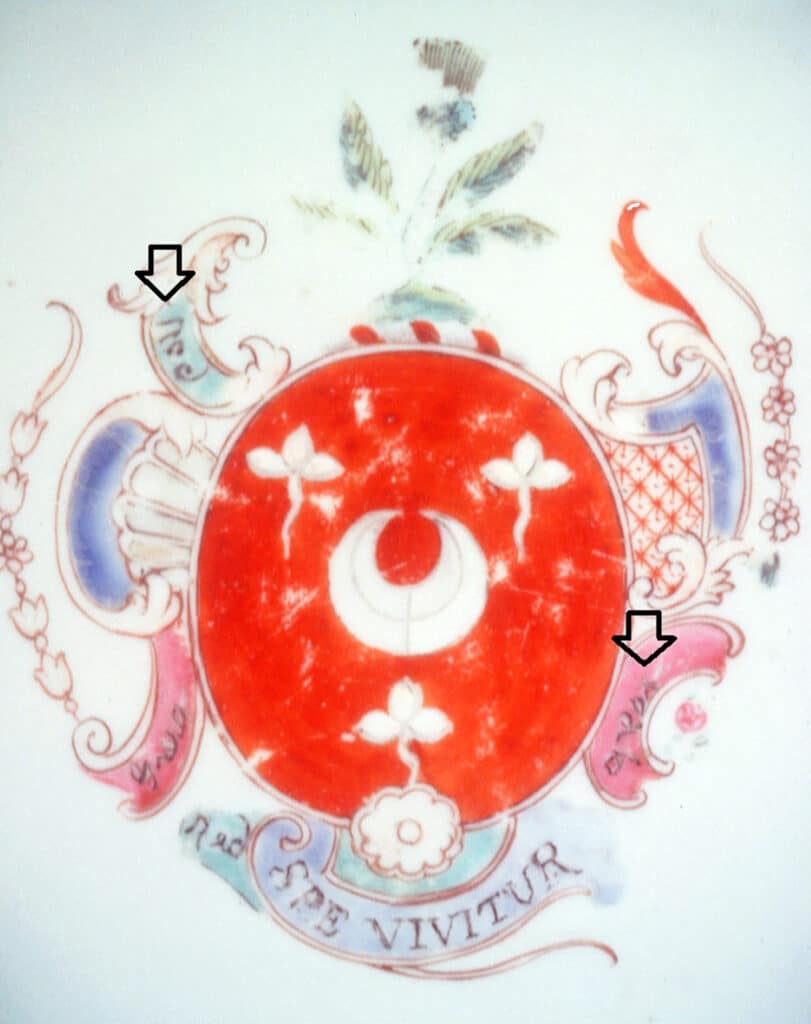

The Dobree Family’s Frustration

Errors could also sting. Take the English Dobree family, who in the 1750s ordered a porcelain armorial service decorated with their red shield and green mantle. What arrived from China was dazzling—but wrong. The shield was indeed red, but the scrolls were painted the wrong color, even though the instructions had carefully indicated in writing what the colors should be.

The Dobree service epitomizes the fragility of communication in a world without shared language or quick corrections.

Why? Because the Chinese artisan had mistaken the instructions for the design. He copied the text, faithfully reproducing “green here” and “red here” into painted reality. The family must have groaned. Worse still, this was their fifth attempt. Four earlier orders had been rejected for other mistakes. At last, they surrendered, accepting this miscolored but now historically precious set of dishes.

For me, the Dobree service epitomizes the fragility of communication in a world without shared language or quick corrections. Instructions passed from the English patron to the ship’s captain, then to the Chinese intermediary in Canton, then 600 miles inland to Jingdezhen, China, where artisans carried them out. The porcelain then traveled back to Canton, across oceans, and eventually to England—a two- to three-year cycle full of opportunities for misinterpretation. Each link in the chain offered the chance for delightfully human error.

A Crucifixion with Asian Features

Christian iconography also proved treacherous. One teapot in my collection depicts the Crucifixion—but in a way no European would recognize. Christ has Asian features. The two figures flanking the cross are both female, though one was meant to represent St. John. And above the cross, instead of “INRI,” the inscription shows three I’s rather than two.

The dealer who sold it to me tried to discourage the purchase. “It’s too ugly,” he warned. He wasn’t wrong. The teapot is far from beautiful. But to me, its very oddness was irresistible. It revealed how unfamiliar the subject matter was to the Chinese painter. To him, these were not sacred Western figures but exotic instructions to be rendered as best he could. To me, it was another thrill to my novelty center, another echo of that first punch bowl discovery.

Why These Mistakes Matter

Why did so many errors occur? The answer lies in the extraordinary chain of transmission that produced every piece of Chinese export porcelain. Perfection, under such circumstances, was a near miracle. Mistakes were not just probable; they were inevitable. To me, those mistakes were what made the pieces come alive. They capture the fragile, uncertain beauty of human communication, our desire to connect, to imitate, to please, and sometimes to misunderstand.

Collecting Errors, Collecting Stories

My collection has grown around these anomalies, these cultural misfires that have become treasures. Some collectors chase flawless famille rose plates or pristine blue-and-white vases. I lean toward errors: letters out of place, mantles the wrong color, puzzle jugs that don’t pour.

And here’s the irony: while my collection began with an “ah ha!” spark in the brain—the thrill of novelty—it has also brought connection. Other collectors, those who care little for perfection, are drawn to the pieces with mistakes. They want to hear the stories, to laugh at the puzzle jug that never worked, to marvel at the Dobree family’s failed services.

The errors become conversation starters, not dead ends. They invite curiosity, speculation, and sometimes sympathy for the poor eighteenth-century family waiting years for a service they never asked for.

Epilogue: The Value of the Oddball

I return, finally, to that punch bowl with its awkward superscript e. Had it been perfect, I might have overlooked it. But it was not perfect. It was human, full of its journey, full of the frailty of distance and translation.

In collecting these flawed treasures, I collect not only porcelain but stories of error, of novelty, and of the human brain’s deep love for the oddball. These mistakes, far from diminishing the value of the objects, have elevated them—at least for me—to the most treasured pieces I own.

For perfection may be admired, but mistakes are remembered.

Adapted from Shirley M. Mueller, Inside the Head of a Collector: Neuropsychological Forces at Play (Lucia/Marquand, 2019), chapter two.

Shirley M. Mueller, M.D., is known for her expertise in Chinese export porcelain and neuroscience. Her unique knowledge in these two areas motivated her to explore the neuropsychological aspects of collecting, both to help herself and others as well. This guided her to write her landmark book, Inside the Head of a Collector: Neuropsychological Forces at Play. In it, she uses the new field of neuropsychology to explain the often-enigmatic behavior of collectors. Shirley is also a well-known speaker. She has shared her insights in London, Paris, Shanghai, and other major cities worldwide as well as across the United States. In these lectures, she blends art and science to unravel the mysteries of the collector’s mind.