Page 23 - Layout 1

P. 23

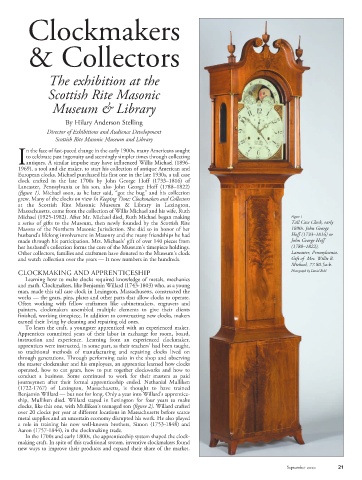

Clockmakers

& Collectors

The exhibition at the

Scottish Rite Masonic

Museum & Library

By Hilary Anderson Stelling

Director of Exhibitions and Audience Development

Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library

n the face of fast-paced change in the early 1900s, many Americans sought

to celebrate past ingenuity and seemingly simpler times through collecting

Iantiques. A similar impulse may have influenced Willis Michael (1896-

1969), a tool and die maker, to start his collection of antique American and

European clocks. Michael purchased his first one in the late 1930s, a tall case

clock crafted in the late 1700s by John George Hoff (1733–1816) of

Lancaster, Pennsylvania or his son, also John George Hoff (1788–1822)

(figure 1). Michael soon, as he later said, “got the bug” and his collection

grew. Many of the clocks on view In Keeping Time: Clockmakers and Collectors

at the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library in Lexington,

Massachusetts, come from the collection of Willis Michael and his wife, Ruth

Michael (1925-1982). After Mr. Michael died, Ruth Michael began making Figure 1

a series of gifts to the Museum, then newly founded by the Scottish Rite Tall Case Clock, early

Masons of the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction. She did so in honor of her 1800s. John George

husband’s lifelong involvement in Masonry and the many friendships he had Hoff (1733–1816) or

made through his participation. Mrs. Michaels’ gift of over 140 pieces from John George Hoff

her husband’s collection forms the core of the Museum’s timepiece holdings. (1788–1822),

Other collectors, families and craftsmen have donated to the Museum’s clock Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

and watch collection over the years — It now numbers in the hundreds. Gift of Mrs. Willis R.

Michael, 77.80.5a-k.

Photograph by David Bohl

CLOCKMAKING AND APPRENTICESHIP

Learning how to make clocks required knowledge of metals, mechanics

and math. Clockmakers, like Benjamin Willard (1743-1803) who, as a young

man, made this tall case clock in Lexington, Massachusetts, constructed the

works — the gears, pins, plates and other parts that allow clocks to operate.

Often working with fellow craftsmen like cabinetmakers, engravers and

painters, clockmakers assembled multiple elements to give their clients

finished, working timepiece. In addition to constructing new clocks, makers

earned their living by cleaning and repairing old ones.

To learn the craft, a youngster apprenticed with an experienced maker.

Apprentices committed years of their labor in exchange for room, board,

instruction and experience. Learning from an experienced clockmaker,

apprentices were instructed, in some part, as their teachers’ had been taught,

so traditional methods of manufacturing and repairing clocks lived on

through generations. Through performing tasks in the shop and observing

the master clockmaker and his employees, an apprentice learned how clocks

operated, how to cut gears, how to put together clockworks and how to

conduct a business. Some continued to work for their masters as paid

journeymen after their formal apprenticeship ended. Nathanial Mulliken

(1722-1767) of Lexington, Massachusetts, is thought to have trained

Benjamin Willard — but not for long. Only a year into Willard’s apprentice-

ship, Mulliken died. Willard stayed in Lexington for four years to make

clocks, like this one, with Mulliken’s teenaged son (figure 2). Willard crafted

over 20 clocks per year at different locations in Massachusetts before scarce

metal supplies and an uncertain economy disrupted his work. He also played

a role in training his now well-known brothers, Simon (1753-1848) and

Aaron (1757-1844), in the clockmaking trade.

In the 1700s and early 1800s, the apprenticeship system shaped the clock-

making craft. In spite of this traditional system, inventive clockmakers found

new ways to improve their products and expand their share of the market.

September 2020 21