Page 24 - Layout 1

P. 24

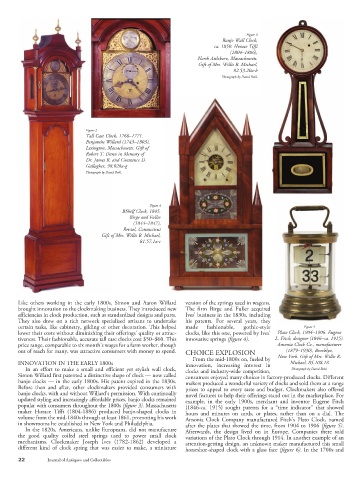

Figure 3

Banjo Wall Clock,

ca. 1850. Horace Tifft

(1804–1886),

North Attleboro, Massachusetts.

Gift of Mrs. Willis R. Michael,

82.53.20a-b

Photograph by David Bohl.

Figure 2

Tall Case Clock, 1766–1771.

Benjamin Willard (1743–1803),

Lexington, Massachusetts. Gift of

Robert T. Dann in Memory of

Dr. James R. and Constance D.

Gallagher, 98.028a-g

Photograph by David Bohl.

Figure 4

BShelf Clock, 1845.

Birge and Fuller

(1844–1847),

Bristol, Connecticut

Gift of Mrs. Willis R. Michael,

81.57.1a-c

Like others working in the early 1800s, Simon and Aaron Willard version of the springs used in wagons.

brought innovation to the clockmaking business. They introduced new The firm Birge and Fuller acquired

efficiencies in clock production, such as standardized designs and parts. Ives’ business in the 1830s, including

They also drew on a rich network specialized artisans to undertake his patents. For several years, they

certain tasks, like cabinetry, gilding or other decoration. This helped made fashionable, gothic-style Figure 5

lower their costs without diminishing their offerings’ quality or attrac- clocks, like this one, powered by Ives’ Plato Clock, 1904–1906. Eugene

tiveness. Their fashionable, accurate tall case clocks cost $50–$60. This innovative springs (figure 4). L. Fitch, designer (1846–ca. 1915).

price range, comparable to six month’s wages for a farm worker, though Ansonia Clock Co., manufacturer

out of reach for many, was attractive consumers with money to spend. CHOICE EXPLOSION (1879–1930), Brooklyn,

From the mid-1800s on, fueled by New York. Gift of Mrs. Willis R.

INNOVATION IN THE EARLY 1800s innovation, increasing interest in Michael, 85.108.18

In an effort to make a small and efficient yet stylish wall clock, clocks and industry-wide competition, Photograph by David Bohl.

Simon Willard first patented a distinctive shape of clock — now called consumers enjoyed many choices in factory-produced clocks. Different

banjo clocks — in the early 1800s. His patent expired in the 1830s. makers produced a wonderful variety of clocks and sold them at a range

Before then and after, other clockmakers provided consumers with prices to appeal to every taste and budget. Clockmakers also offered

banjo clocks, with and without Willard’s permission. With continually novel features to help their offerings stand out in the marketplace. For

updated styling and increasingly affordable prices, banjo clocks remained example, in the early 1900s, merchant and inventor Eugene Fitch

popular with consumers throughout the 1800s (figure 3). Massachusetts (1846-ca. 1915) sought patents for a “time indicator” that showed

maker Horace Tifft (1804-1886) produced banjo-shaped clocks in hours and minutes on cards, or plates, rather than on a dial. The

volume from the mid-1840s through at least 1861, promoting his work Ansonia Clock Company manufactured Fitch’s Plato Clock, named

in showrooms he established in New York and Philadelphia. after the plates that showed the time, from 1904 to 1906 (figure 5).

In the 1820s, Americans, unlike Europeans, did not manufacture Afterwards, the design lived on in Europe. Companies there sold

the good quality coiled steel springs used to power small clock variations of the Plato Clock through 1914. In another example of an

mechanisms. Clockmaker Joseph Ives (1782-1862) developed a attention-getting design, an unknown maker manufactured this small

different kind of clock spring that was easier to make, a miniature horseshoe-shaped clock with a glass face (figure 6). In the 1700s and

22 Journal of Antiques and Collectibles