Fire & Vine: The Story of Glass and Wine by Judy Gonyeau, managing editor

with Katherine Larson, curator of ancient glass, CMoG

Courtesy of Corning Museum of Glass

The entwined histories of glass and wine extend back thousands of years, from lavish feasts of ancient Rome to the polite society of Britain in the 1700s, to formal dinner parties of post-war America, to an essential experience within our contemporary food culture. The strength, impermeability, and versatility of glass have played an important role in every step of wine’s journey, from the production, distribution, sale, and ultimately the enjoyment of this intoxicating beverage.

On Exhibit

Fire & Vine: The Story of Glass and Wine has been on exhibit at the Corning Museum of Glass (CMoG) since July 3, 2021 and will continue to be on view through the end of 2022 – a lucky thing for people who have not had the chance to travel and visit amid an ongoing pandemic. This exciting exhibition just happens to be near the New York State Finger Lakes wine district (there are eleven designated American Viticultural Areas in New York – the Finger Lakes region was established in the 19th century). Sponsors of the exhibition are Finger Lakes Wine Country (in Corning), Dr. Konstantin Frank Winery in nearby Hammondsport, and the Pleasant Valley Wine Company, just a few minutes from the Frank Winery, all off of Route 390/86.

Aside from the culture and adventure of traveling through New York State’s wine country is the chance to learn glass’s broader role in the science, creativity, and history of wine from thousands of years ago to today. This is one venture where science and nature came together to form a libation steeped in history and sipped and celebrated over time.

To many people, the story of glass and wine is a tale of hedonism, about the experience of tasting wine from a fine piece of hand-blown stemware. To others, it is a story of strength, of the glass bottles that make champagne and other sparkling wines possible, because they can contain the pressure of carbonation. And to others still, glass tools are critical to the process of winemaking, helping to ensure a successful harvest and fermentation.

Ancient Times

In a 2017 article from BBC News, Scientists had discovered an 8,000-year-old pottery fragment containing evidence of the earliest making of grape wine. These were discovered in Georgia, a country located at the intersection of Europe and Asia along the Black Sea. On those jars were images of grape clusters and a man dancing. Apropos for the early beginnings of this drink of the gods.

It was not until 4,000 years later in 2,000 BC that glass was first being made. This glass was not the clear, delicate glass used to see and drink wine today, but was opaque and made to look like they were made of precious stones. These were used in many ceremonies that were religious and political in nature, giving wine the power to seal a deal between adversaries by adding meaning to negotiations made over feasts and momentous events as they clinked glasses and adding sound to the signs of peace.

On display at CMoG is a rare fragment of cameo glass made sometime between 25 BCE to 50 CE from the Mediterranean, probably Italy. This piece of glass was either cast or blown from two layers of glass, and the white glass was partially carved away to create a detailed scene. The image on the glass is of a worker carrying a harvest of grapes. The fragment is just 1.75” wide by 2” high. The vessel it came from is estimated to be 4.75” overall. The artistry is intricate and realistic. This is just a glimpse of the artistic inspiration that arose from the process of making wine.

Storing Wine

Over the centuries, winemakers studied the many components used in making wine. Refining the type of grape through breeding for the best flavor, most output, ability to sustain over time. Grapes were grown all over the world but how weather, temperature, light, soil content, and accessibility to the market all played a role in the varieties of wine developed over time. With the immense attention given to the creation of wine, storing it was another issue altogether.

Storage of wine was critical from its invention. Prior to the 1800s, wine was kept in large ceramic containers or wooden casks. It was a race against time to get the wine from the producer to the consumer before it spoiled due to oxidation. The more affluent were able to buy wine in bulk using wooden barrels and large pottery urns that were stored in the cellars where light and moving air were not an issue when it came to preserving its taste and quality. Those who could not afford to purchase wine in bulk instead filled their own containers at local wine shops or taverns, similar to the way we fill growlers at breweries today.

By the early 1800s, wineries themselves began to store and ship their product in glass bottles, with paper labels with information about the winery and vintage replacing the stamps with names of individuals and taverns who used the bottle. The introduction of a three-part molded bottle in the 1820s solidified the standard cylindrical shape of the wine bottle which is still recognizable 200 years later.

Making Wine Portable

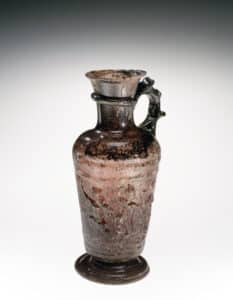

In the early 1600s in England, glass was becoming a more common material to conduct those purchases. As John Worlidge pointed out in his treatise on glass bottles in 1676, glass was stronger, less apt to leak, less likely to taint the contents than ceramic jugs. Glass was also transparent, and so easier to monitor the contents and determine if the vessel was clean.

“Glass bottles are preferred to stoneware bottles because stone bottles are apt to leak, and are rough in the mouth, that they are not easily uncorked; also they are more apt to taint than the other; neither are they transparent, that you may discern when they are foul, or clean.”

– John Worlidge, 1676

The robust British glass wine bottle of which Worlidge spoke was helped along by a quirk of glass history: early in the 1600s, King James I of England forbid glasshouses to use wood-fired furnaces in glassmaking. Glass houses switched to coal as a fuel source. Because coal burns hotter than wood, glassmakers could increase the ratio of silica to sodium in the glass batch, resulting in a stiffer, stronger glass. Coal furnaces are also reducing environments, which has the effect of deepening the green color of the iron in the glass. Stronger, thicker, and darker glass than what had been available previously contributed to a bottle that was more conducive to long-term storage of wine.

Serving Wine at Home

Back before the wine bottle was an everyday convenience used to purchase and store wine, those hefty wooden barrels in the cellar made it difficult to bring wine to the serving area without having to bring the entire cask into the household. Some homeowners would install pipes from the basement to the dining area to dispense wine into crocks or other serving pieces. But the experience of serving wine was brought up a level in the mid-1700s by the use of Wine Urns – much like the metal samovar but made of glass with a spigot for serving. Such a convenience was yet another showcase piece to reflect the owner’s wealth and strong sense of style.

CMoG has a beautiful lead glass accented with pewter Covered Wine Urn with Standard from Ireland in its collection. Made in about 1785, this cut-glass beauty stands just over two feet tall and, unfortunately, could not fit in the display cases within the exhibit. Not to be missed is a demonstration on the making of this delicate glass piece filmed in 2021 and available to view on YouTube or by using a line at www.cmog.org

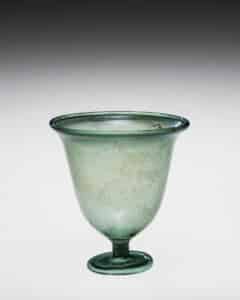

The enjoyment and satisfaction to be had when drinking wine from a glass drinking vessel became popular very quickly. People have drunk wine from glass for more than 2,500 years, and the first stemmed goblets were made more than 1,500 years ago. Beyond the general endurance of the stemmed shape, wine goblets appear in all shapes, sizes, colors, patterns, glass techniques, and more, speaking to the wide variety of drinking customs and the various roles wine played different societies. The Roman satirist Petronius noted around 60 CE that he preferred glass because it doesn’t smell and it provides a better tasting experience than gold – although prone to breakage.

The Evolution of the Wine Glass

According to Katherine Larson, goblets like the stemmed glasses we recognize as today’s wine glasses started to appear in the 3rd and 4th centuries. “Sometimes they have handles; sometimes, they don’t,” she says. “They start popping up from that era in the area that is now Israel, Lebanon, Syria—that area of the Eastern Mediterranean—and then that style of glass expands throughout the ancient Roman world and beyond.”

Courtesy of Corning

Museum of Glass

In the 1700s and 1800s, a standard service of glassware for a wealthy person in western Europe or America may have included different glasses for cordials and spirits, brandy, punch, sherry, champagne, ale, and cider, but only one glass designated for wine. Occasionally, glasses may have been marked for popular wines like claret or Madeira.

Red and white wine glasses start to appear around the turn of the 20th century. In the post-World War II economic boom, the Austrian glass company Riedel paired up master glassblowers with wine experts to create a series of stemware that would optimize the tasting experience for different varietals of wine. The resulting “Sommeliers” series of glasses is a refined and elegant service that showcases the talents of glassmakers and winemakers alike.

A focal point of Fire & Vine is a dense display of dozens of wine glasses from around the world, representing many styles and tastes, fit for a variety of occasions. The delicate stemware has been part of countless life moments. The oldest piece of wine drinkware featured in the exhibit is more than 2,500 years old.

This display does follow the trend that wine glasses have gotten bigger over time. “A 2017 British Medical Journal report found that the capacity of the average wine glass increased seven times between 1700 and 2017, with the biggest jumps in size occurring in the 1980s and 1990s,” as noted in a pix.wine article.

Winemaking and Science

Courtesy of Corning Museum of Glass

According to Chris Gerling and Anna Katharine Mansfield of Cornell AgriTech in a post they provided to CMoG, they explain the role of “wine” and “laboratory” this way: “(they) don’t have a lot in common – one’s an agricultural product steeped in history and tradition, and the other is the sterile domain of lab-coated scientists. As it turns out, the art of wine involves a lot of science, and the science of wine involves a lot of glass! Even the least scientific among us are familiar with the cartoon images of wildly-shaped glassware full of brightly-colored bubbling liquids … and, yes, the wine lab has stuff like that. But we use glass to analyze grapes and wine in all sorts of unexpected ways, starting in the vineyard.”

In the vineyard, grape growers use a tool called a refractometer, which contains a glass prism, to measure the amount of sugar present in the grape and determine the precise moment to harvest. After the grapes are harvested and pressed, the resulting juice ages in barrels. As the wine ages, winemakers extract small samples for tasting with a glass tube called a wine thief. The Volatile Acid Still tests for volatile acids such as vinegar, which are caused by the presence of bacteria, and a glass hydrometer measures the sugar and alcohol content in the wine. By floating a glass hydrometer in the fermenting liquid, winemakers can determine when aging is complete.

The Exhibit Regional

Courtesy of Corning Museum of Glass

In the midst of the pandemic, CMoG was looking for exhibits that could be found mainly within its collections that would complement another important exhibit on view – In Sparkling Company (this exhibit closed at the beginning of 2022). The criteria were clear and informed by the pandemic moment: draw from the strengths of our permanent collection, include objects from across time and space (including materials from the Rakow Research Library), appeal to local and regional audiences, and feel celebratory and uplifting, reflecting our collective battle against COVID-19 and looking toward a brighter future.

Katherine Larson stated that “During fall 2020, with limited access to the Museum itself, I combed Museum databases and publications to identify potential objects for the exhibition. A number of gems came to light. … (and) I began to realize that the Museum’s collection lacked objects connected to the story of wine in the Finger Lakes, a narrative that everyone on the exhibition team agreed was important to include. I connected with local winery owners from whom I learned about the surprisingly long and rich history of wine in the region. Although I’d enjoyed a few wine tours and samples at local tasting rooms, I didn’t recognize that wine has been made in the Finger Lakes even longer than glass has—and that Finger Lakes wineries were pioneers in growing European grapes on the east coast of North America in the mid-20th century.”

The history of the New York State wine industry is presented in concert with the story of glass within the history of winemaking and glass innovation over time. Just as all the senses are in play when testing and tasting wine, experiencing it within a wine region makes the experience all the sweeter.

Fire & Vine: The Story of Glass and Wine is on view at the Corning Museum of Glass’ Gather Gallery through December 2022. Learn more at www.cmog.org

Related posts: