Our October issue explores the historical roots of the American harvest. You may question what that has to do with antique collectibles but in their own way, the indigenous seeds we found here and those brought over from other countries, often referred to as heirloom seeds, spawned an agro-industry that today exports over $140 billion worth of American agricultural products around the world.

According to a recent article in Time magazine, over the past 50 years, agricultural practices have changed dramatically. Although technological advances have facilitated large-scale crop production and increased crop yields, biodiversity has decreased to the point that now only about 30 crops provide 95 percent of human food-energy needs. As an example, the U.S. has lost over 90 percent of its fruit and vegetable varieties since the 1900s. This leaves remaining food supplies more susceptible to threats such as diseases, drought, and climate change. Staples such as wheat and corn are likely to be among the most vulnerable to wild weather, pests, and disease.

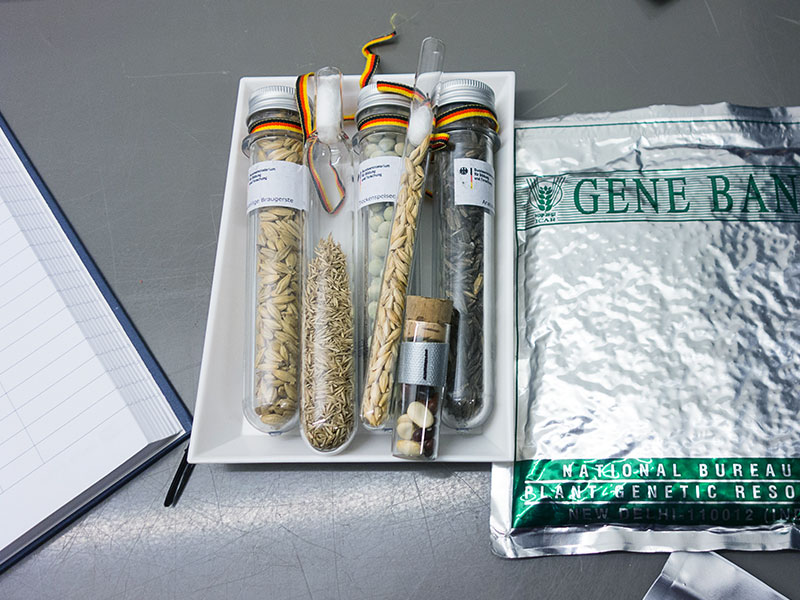

The idea of warehousing seeds to preserve the genetic make-up of crops important or unique to a region is not new. There are more than 1,700 genebanks worldwide holding collections of food crops for safekeeping. Yet, history has shown them vulnerable to natural catastrophes, war, climate change, and poor agricultural management. Something as mundane as a poorly functioning freezer can ruin an entire collection. Crop extinction is as irreversible as the extinction of a dinosaur, animal, or any form of life. A safer, longer-term solution was required.

An insurance policy for the future

Deep inside a mountain on a remote island in the Svalbard archipelago, halfway between mainland Norway and the North Pole, lies the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, an underground, naturally preserving cold storage facility built to protect the seed of crops important for food and agriculture around the world for future generations.

The idea of an underground seed vault as an insurance policy against the challenges being faced by agri-growers and traditional genebanks was conceived in the 1980s, but the plan to build one was accelerated after an International Seed Treaty negotiated by the U.N. was signed in 2001. The vault officially opened in February 2008.

Dubbed the “doomsday” vault, Svalbard’s three underground chambers have the capacity to store 4.5 million varieties of crops (each variety contains on average 500 seeds), representing every important crop variety available in the world today, for hundreds to thousands of years as a backup for the world’s crop collections.

Twice a year, the Vault opens for deposits. Currently, it is holding more than 1,000,000 samples, originating from almost every country in the world. Its seeds range from unique varieties of major African and Asian food staples such as maize, rice, wheat, cowpea, and sorghum, to European and South American varieties of eggplant, lettuce, barley, and potato. In fact, the Vault already holds the most diverse collection of food crop seeds in the world.

One of the most historically significant deposits of seeds inside the vault comes from a collection in St. Petersburg’s Vavilov Research Institute, which originates from one of the first collections in the world. During the siege of Leningrad, about a dozen scientists barricaded themselves in the room containing the seeds to protect them from hungry citizens and the surrounding German army.

As the siege dragged on, a number of them eventually died from starvation. Despite being surrounded by seeds and plant material, they steadfastly refused to save themselves by eating any of it, such was their conviction about the importance of the seeds to aid Russia’s recovery after war and to help protect the future of humankind. One of the scientists, Dmitri Ivanov, is said to have died surrounded by bags of rice.

U.S. Involvement

Participation in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault endeavor has given the United States a visible presence in the worldwide effort to safeguard the genetic diversity that underpins our food supply. It has also been a way for ethnic groups to preserve for prosperity foods indigenous to their culture and their roots.

In 2020, The Cherokee Nation became the first US Tribe to deposit culturally important crop seeds in the Svalbard Vault. The Cherokee Nation’s Office of Natural Resources collected nine samples of Cherokee heirloom crop seeds, including the Cherokee White Eagle Corn – a blue and white corn with a red cob that gets its unusual moniker because some kernels appear to display an image of a white eagle. White Eagle Corn is the tribe’s most sacred corn and is used in important cultural activities. Other seeds sent to the Seed Vault include Cherokee Long Greasy Beans, Cherokee Trail of Tears Beans, Cherokee Turkey Gizzard black and brown beans, and Cherokee Candy Roaster Squash, along with several more varieties of corn. All nine Cherokee crop varieties sent to Svalbard predate European colonization.

When we think back on foods we enjoyed as a child that are no longer available today, and why, it is easy to understand the urgency behind the Svalbard Seed Vault’s mission and the importance of heritage foods. In this form of collection preservation, future generations will be able to connect with their culture’s foodways with this organic form of their preserved heritage.

Related posts: