by Kary Pardy

Do You Know Where You’re Going To?

In 1714, the British Parliament established the Longitude Act, and with it, the Longitude Rewards. Equivalent to just over a million dollars today, these prizes offered rewards to any who could come up with a reliable way to measure longitude at sea. Latitude was simple enough and could be measured relative to the altitude of the sun at noon, but longitude proved much trickier. The old method, dead reckoning, was based on the speed the vessel was traveling and the vessel’s direction, and was dangerously inaccurate when sailors got too far from land. Add in the problem of magnetic north vs true north (which can vary by a critical 10 degrees in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans), and you get several deadly shipwrecks, including the destruction of a British naval squadron off the coast of Sicily in 1707. It was time to find, and fund, a better way.

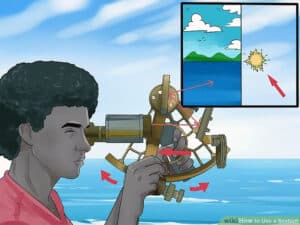

Enter English mathematician John Hadley and Philadelphia glazier Thomas Godfrey, who both developed similar solutions around 1731. They developed an instrument, the octant, that uses two mirrors to measure celestial bodies above the horizon via angles up to 90 degrees. The octant was refined to a sextant, named because it enlarged the octant (1/8 of a circle) to 1/6th of a circle, and now measurements of up to 120 degrees were possible. While the octant could reliably calculate your position on a nautical chart by calculating the sun or the North Star’s angle to the horizon at a given time, the sextant’s larger angle could accurately measure lunar distance between the moon and another celestial object to determine Greenwich Mean Time, an invaluable component when determining longitude.

Enter: The Sextant

cases. The handle is also separated from the frame so that body heat cannot impact the frame over time. Sailors in tropical climates combat this weakness by painting their sextant’s white to reflect

sunlight and keep cool. Sextant circa 1865.

photo: Cooper Hewitt Collection, on loan from the Smithsonian National Museum of American History

The sextant was a game-changer – not only could it plot a location with accurate latitude and longitude, but it also addressed the challenges of past technologies. A sextant measures celestial objects relative to the horizon, which makes it more precise than a purely instrumental measurement. Even when bouncing around on a rolling sea, a sextant will read accurately because both the horizon and the celestial object will move in the field of view and the angle (the most important part of the measurement) will stay the same. It also has the advantage of working at night, as you can measure off the stars.

The sextant caught on quick for its reliability and precise readings, and saved lives in the process. A famous tale of sextant use comes from Ernest Shakelton’s Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914-1916). When Shackleton’s ship Endurance got caught in pack ice and crushed, the crew took lifeboats to Elephant Island where they were stranded upon arrival. Captain Frank Worsley used a Heath & Co. sextant to navigate himself, Shackleton, and four crewmen 800 nautical miles through dangerously rough seas to find help on South Georgia Island, ultimately saving the crew. The same “Hezzanith” sextant is now in the collection of the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge.

Long Live the Sextant

You also can’t beat this technology for its staying power. The basic design of the sextant has not changed since the 18th century, and they were still being used up until about 30 years ago when GPS became the new normal. At their best, a sextant can place you within a mile and a half of your actual location, which explains why their use got much more infrequent in the wake of something that could place you with only a foot or so of error. They are not yet obsolete, however. The US Navy still trains sailors in celestial navigation and sextant use as a backup should GPS (or electricity, in some cases) fail. The sextant has the added bonus that it’s not vulnerable to hacking, which is becoming an increasing concern.

A Piece of Technology to Collect

What about collectibility? Today, firms like Weems & Plath still manufacture sextants, but the majority of them are purchased by private sailors as backups. Older sextants are part of a niche group of antique maritime and navigational technology that found its audience in England among sailing enthusiasts and interior decorators, and headed west.

Now, more than ever, sextants find places of prominence among technology or maritime collections, in gentleman’s libraries, or as an homage to exploration paired with a classic ship portrait. Antique sextants can bring anywhere from hundreds to several thousand dollars if in top condition. As essential navigation tools, sextants were typically treasured by sailors who might have received or proudly purchased one as they progressed up the ranks.

Collectors will benefit from the fact that they were often well-cared for and frequently come with their boxes, a testament to the antique sextant’s place of honor on any ship. Sextants also got passed down when sailors retired, taking on multiple generations of significance. They were such prominent symbols that you’ll even find sextants and octants carved into tombstones, particularly those of New England sea captains, to chart their way to heaven.

Variants on This Theme

Looking for something a little earlier? Check out the cross-staff, a wooden rod that forced sailors to look at the sun, or the back staff, which fortunately allowed the user to take measurements with the sun behind him. The astrolabe is equally rare, but you can find these and other outmoded navigational instruments at auction or via specialty dealers, such as Tesseract of Hastings on Hudson or George Glazer Gallery in New York City. Fleaglass.com also compiles several venues that carry antique science and technology. Be prepared to pay in the low thousands at least for these instruments from dealers, but particularly with sextants, the cost can be worth it for this functioning piece of maritime history. Owning one might just save your life someday.

Related posts: