Negro League Baseball got its start thanks to the increasing popularity of two things after the Civil War: baseball and segregation.

Even before the Civil War, African Americans were playing America’s great pastime – baseball. Records exist of an abbreviated game between two Black teams as far back as 1855.

In the decades following the War, African American players started to play on military teams, college teams, and company teams, and formed clubs of their own in the New York area. Eventually, some of these players even found their way to professional teams with white players, but that was not tolerated for long. In 1867, the National Association of Base Ball Players rejected African American membership, and in 1876, owners of the newly formed (1871) National Association of Professional Base Ball Players adopted a “gentleman’s agreement” to keep Black players out.

Overcoming Segregation and Conflict

Moses Fleetwood Walker and Bud Fowler were among the first African American players to play on a team with white players; however, racism and “Jim Crow” laws would force them from these teams by 1900. In response, black players formed their own teams, “barnstorming” around the country to play anyone who would challenge them.

In 1884, catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker of the Toledo Blue Stockings became the first African American to play in what was then considered a major league. However, Walker and fellow African Americans often faced outright hostility and physical intimidation from both teammates and opponents. In one case, 19th-century superstar Cap Anson of the Chicago White Stockings threatened to cancel a game with Toledo if Walker was in the lineup.

Segregation notwithstanding, Black players continued to find ways to foster high-level competition in major northern cities. The first “Colored Championship of the World” was held in 1903, with pitcher Rube Foster leading the Cuban X-Giants to victory over the Philadelphia Giants.

The Negro National League

In 1920, Rube Foster launched the Negro National League (NNL) with eight teams: Chicago American Giants, Chicago Giants, Cuban Stars, Dayton Marcos, Detroit Stars, Kansas City Monarchs, Indianapolis ABCs, and the St. Louis Giants. The league’s early financial success prompted the formation of the Eastern Colored League, an enterprise of Black ownership, in 1923. The two circuits converged to play the World’s Colored Championship in 1924, and continued the annual series until 1927, bringing the thrills and innovative play of black baseball to major urban centers and rural communities across the country. The Leagues maintained a high level of professional skill and became centerpieces for economic development in many black communities.

Stability, however, proved fleeting for these early Negro Leagues. Players jumped from squad to squad in pursuit of the highest bidder, and teams skipped league games when a more lucrative exhibition offer surfaced. By 1926, Foster’s Negro National League was mired in controversy, and in 1928, its rivals, the Eastern Colored League, folded. The NNL finally fell apart in 1931 under the economic stress of the Great Depression – only a few strong independent clubs survived the 1932 season. While some top teams such as the Leland Giants of Chicago and the Lincoln Giants of New York enjoyed some staying power and financial success, they were often at the mercy of white booking agents who controlled access to large stadiums.

The American Negro League

In 1937, a new entity was formed called the American Negro League with several of the same teams that played in the original Negro National League, providing African American players new opportunities for earning a living while playing a sport they loved.

It was Jackie Robinson’s integration into the major leagues in 1947 that was the eventual undoing of negro baseball, as African American players now saw new opportunities for their future. The remaining Negro League teams generally folded by the 1960s.

Folded … but not forgotten.

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM) in Kansas City, Missouri, was established in a one-room office in 1990 with the mission to preserve and celebrate the rich history of African American baseball and its profound impact on the social advancement of America. Since that time, it has become one of the most important cultural institutions in the world for its work to give voice to a once forgotten chapter of baseball and American history. In July of 2006, the NLBM gained National Designation from the United States Congress earning the distinction of being “America’s National Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.” It is located two blocks from the Paseo YMCA where Andrew “Rube” Foster established the Negro National League in 1920.

“The story of the Negro Leagues is a story of America at her worst, but also at her triumphant best,’’ said Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum since 2011, on the occasion of the League’s 100th Anniversary. “From the ashes of American segregation rose this triumphant conquest, and it’s all based on one simple principle: ‘If you don’t let me play with you, I’ll create a league of my own.’”

With no initial endowment, the Negro League Museum initially sprung from what Kendrick calls “hope and a prayer.’’ “In its early days, former Negro Leaguers wrote out personal checks to help pay the rent.” Today, more than two million visitors have toured the Museum’s over 10,000 square feet of multimedia exhibition space that chronicles the history, heroes, and stories of the leagues from their origin after the Civil War to their demise in the 1960s.

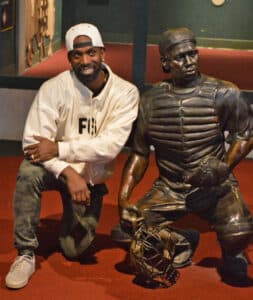

The NLBM is a self-guided tour experience comprised of video presentations and memorabilia. Text panels, hundreds of photographs, artifacts, and several film exhibits are integrated with a timeline of baseball and African American history to tell the stories of the times as well as the players. As the centerpiece of the NLBM, the Coors Field of Legends features 10 life-sized bronze sculptures of Negro Leagues greats positioned on a mock baseball diamond as if they were playing a game. A documentary film narrated by actor James Earl Jones tells the story of the leagues with vintage film footage. The Hall of Fame Lockers pay tribute to the Nego Leaguers who have been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

While many may know about and recognize the accomplishments of Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Ernie Banks, these and other Hall of Famers got their start in the Negro Leagues before going on to Major League Baseball stardom. The Museum shares not only their stories but those of such lesser-known but no less influential African American players as “Rube” Foster, Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Satchel Paige, and John “Buck” O’Neil, among others.

For those unable to travel to Kansas City, the Museum has created five uniquely different national traveling exhibitions that offer interesting and entertaining perspectives on the scope and magnitude of the professional Negro Baseball Leagues and their impact on the social advancement of America.

Moving Forward

Keeping the Museum’s mission alive is still based on “hope and a prayer,” but with the help of some new partnerships, new fundraising opportunities are on the horizon.

In July of 2021, Music City Baseball’s (MCB) Music Industry Advisors partnered with the Museum, Adidas, Topps Trading Cards, and the Fluent Group to launch an exclusive new series of Stars rookie cards and jerseys to honor former Negro Leagues players. MCB’s Music Industry Advisors include: Kane Brown, Luke Combs, and Willie Jones. Advisors and former Negro Leagues players are featured on the cards; the advisors are rocking their Nashville Stars Adidas jerseys, and the back of the card describes a Negro League story or player that most resonated with each advisor.

In November, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the United States Mint unveiled the Negro Leagues Centennial Commemorative Coins to honor the 100th anniversary in 2020 of the Negro Leagues. The commemorative coins are scheduled to be issued in 2022 and will be of no cost to taxpayers. According to the official press release, “after the U.S. Treasury has recouped all its costs for designing and minting the coins, funds will be distributed in support of the NLBM … The coins could generate as much as $6 million in support of the NLBM.”

These types of collaborations could be a real game-changer for the Museum and its important mission to preserve and share the African American experience and influence on America’s greatest pastime. Learn more about the Museum and the stories it tells at www.nlbm.com.

Related posts: