By Judy Gonyeau, managing editor

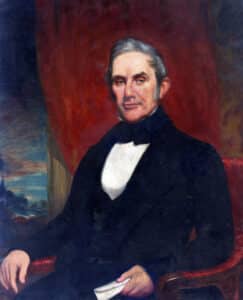

The town of Ansonia, Connecticut, owes its name and fame to Anson Green Phelps – entrepreneur, businessman, and community supporter. Not only was he known for clocks, but imported goods from England including brass, tin, iron, and tin plate, his talent for making and selling saddles to southern states, exporting cotton to England, and the Ansonia Clock Company. Phelps was a fast-moving, multi-talented businessman who knew who to work with and when, and had the statistics to prove it.

On The Move

Anson Phelps was born on March 24, 1781, in Simsbury, Connecticut, and descended from early American governors of Connecticut Thomas Dudley (1596-1653), John Haynes (1594-1653/4), and George Wyllys (1590-1645), no doubt contributing to his pioneering spirit.

Phelps was raised in the home of a Congregational minister following the death of his mother when he was just 12 years old. At 18, he selected his relative, Thomas Woodbridge Phelps, as his guardian.

Once he became somewhat independent, Phelps moved to Hartford, Connecticut, and started a saddlery business that would ship them to the South. He was very successful and constructed a large brick building for manufacturing that became known as “Phelps Block.” Then, at the age of 31, Phelps made a move to New York City and partnered with Elisha Peck of Liverpool, England, to build an import company, Phelps, Peck & Co., becoming New York’s largest metal importer for a time. He dissolved his partnership with Peck and began Phelps, Dodge, and Company with his two sons-in-law.

While operations were moving smoothly, Phelps found another business partner, Sheldon Smith, with whom he could not only establish a thriving business, but make his mark by building his namesake community in his home state.

Creating Ansonia

Along the Naugatuck River, an area of prime Connecticut property was settled by English colonists in 1652 who established the township of Derby. In 1844, Anson Phelps purchased land along the East side of the river with the intent of building a manufacturing site where he could take advantage of the river for its power and its proximity to shipping ports along the Southern Connecticut coast.

Other businesses also established themselves in this subdivision of Derby that Phelps, his business partners, and the residents soon referred to as “Ansonia.” In short, the area was soon established as a borough of Derby, then a separate township from Derby, and incorporated as a city in 1893. Although Anson Green Phelps passed away in 1858 at age 73, he was able to witness his name being used for the name of the place where his businesses became a worldwide success.

Brass Business in Ansonia

Starting in the 1830s, rolled brass became commercially available in quantity in the U.S., and by 1838 it had replaced cast brass and wood for use in clock movements. For Phelps, the journey to becoming one of the largest suppliers of rolled copper and brass was not necessarily a smooth one.

In 1834, Anson G. Phelps associated himself with Israel Coe, John Hungerford, and Israel Holmes, organized the Wolcottville Brass Company, and established a new industry in Wolcottville (now Torrington) for the making of brass kettles from rolled brass. The kettles were hammered into shape from blanks. Before this, kettles had been cast.

The company brought in a strong workforce to make the rolled brass, but the panic of 1837 broke wide open just as the enterprise was getting started. From the first, the new plant was successful and despite the economic downturn, they gained a strong footing in this new industry.

But then in 1838, the mill burned down. The company was able to immediately rebuild. More workmen and machinery were secured from England. The new mill also made a specialty of copper sheets and wire, and the manufacturing was then largely centered in Ansonia.

The Ansonia Clock Company

Dial within the 12-inch dial, and an overall height of 32 inches. These were produced circa 1901 to 1915. Described as a black walnut case in the catalog, which also has some mahogany veneers applied around the pendulum door. Selling for $1,200 at RubyLane.com

According to The Development of the Brass Industry in Connecticut for the Committee on Historical Publications and written by William Gilbert Lathrop in 1936, Phelps was growing his businesses just as the transition of creating clocks with wooden elements was being switched over to brass. Therefore, it was no surprise that the transition to supplying brass for these new clockworks and their manufacture was almost a no-brainer for Phelps.

With the right partnership, Phelps could easily create a business that bought from his other company. So, in 1938 Phelps turned to two established clockmakers, Theodore Terry and Franklin C. Andrews, to begin manufacturing clocks in a new business arrangement with Ansonia Brass Co. This clockmaking team was already established in Bristol, Connecticut, with over 50 employees, and used over 58 tons of brass to produce about 25,000 clocks a year. With Phelps’ manufacturing prowess, this new partnership would grow to create hundreds of thousands of clocks at the height of their popularity.

Terry and Andrews sold Phelps a 50 percent interest in their business (in exchange for extremely low prices on brass) and moved to Ansonia. In 1851, the Ansonia Clock Company was established as a subsidiary of Phelps, Dodge & Co., the original founding company in Ansonia.

In 1853, the Ansonia Clock Company was one of only four clock manufacturers (all from Connecticut) to exhibit at the July 4 New York World’s Fair. At that point, they were making over 400 different clocks—something for everyone—and showcased its masterfulness by displaying its cast iron clocks that were decorated with mother of pearl and hand-painted motifs along with a vast array of options available for every home and business.

Also that year, Anson Phelps sold his interest in the Ansonia Clock Company to his son-in-law James B. Stokes for him to take the company over. Phelps later died a wealthy man at his New York City home on November 30, 1953.

Just one year later the Ansonia Clock Company was destroyed by fire. The New York Times put it this way: “New Haven, Saturday, July 8 – The large stone factory of the Ansonia Clock Company was wholly destroyed by fire early this morning. The loss exceeds one hundred thousand dollars. Insured for about fifty thousand. The business of the company was conducted by T. Terry and Son.”

According to watchlords.com, “The land and the ruined buildings were bought by the directors of Phelps, Dodge & Co. The shares purchased included the remaining shares owned by the last of the original clock company founders, Theodore Terry. It is interesting to note that Terry thereafter became involved in a clock venture with the great promoter P.T. Barnum. It produced clocks under the name of the Terry & Barnum Manufacturing Company until its bankruptcy in March of 1856.”

Following the fire in 1864, it was not until 1869 that full-scale clock manufacturing resumed. By June of 1870, some impressive successful statistics were evident – the company had manufactured 83,503 clocks, employed 150 workers, and used 90,000 pounds of brass to make the clocks. In 1873, its first published price list offered 45 models and 14 different movements. Ansonia also exported its clock movements overseas. Some of the most highly prized antique clocks made in Europe have Ansonia movements.

In 1877, the Ansonia Clock Company moved its entire business to Brooklyn, New York where the building burned down in 1880. Once again, the company was rebuilt and opened for business within a year. Expansion was on the owners’ minds, and the newest site consisted of a 300,000-square-foot factory complex. Here, Ansonia’s 1,500 employees made more than 10,000 clocks and watches, which they added to their product line, each day. Today, it houses a 71-unit residential co-op.

Watches Join the Clock Enterprise

Ansonia clocks were expensive. They were often placed in the home where they could stand out as a status symbol. When the company attempted to create an inexpensive version of a pocket watch for the average person, the designers chose to go with a Tourbillon watch that was originally created in France by Abraham-Louis Breguet in 1775. Taking the design a step further, they built the case so that the movement would rotate inside.

Millions of the non-jeweled models were sold across 25 years before the watch division went out of business.

The year 1877 is the same year that Henry J. Davies of Brooklyn—also a clockmaker, inventor, and case designer —joined the now-reconfigured Ansonia Clock Company as a founding partner. The good times were at hand. By 1914, the business offered around 450 different clocks and their iron-cased clocks continued to be popular. But, with a broader range of raw materials in manufacturing and changes in taste over time, the Ansonia Clock Company began to drop business starting around 1920 when the selection was down to 136 clocks and 9 watch models.

Then, in 1929, the Ansonia Clock Company business stumbled further with the Great Depression as a somewhat final blow. The Ansonia Clock Company was sold to Russian investors, and the entire company was moved to Moscow.

Meanwhile in Ansonia

Back in the town of Ansonia, the Ansonia Brass Company thrived for decades, only to succumb to a familiar foe for the Phelps’ businesses this time in the 21st century – a fire. The company then closed the day before Thanksgiving, 2013, and made a deal with the town of Ansonia to forgive as much as $400,000 in back taxes in exchange for demolition and clean up of the contaminated properties. In 2015, the owners sold the property to 725 Bank Street Development, Inc., in Cincinnati, Ohio. The property, which even had its own rail stop, had to be remediated and cleaned up to allow for redevelopment.

In 2018, a fire ripped through what many saw as the most beautiful of the buildings left on the site, as if to erase the Phelps legacy. Today, the town of Ansonia works to preserve the legacy of Anson Phelps.

Anson Green Phelps, Philanthropist

As Anson Phelps maneuvered through the business world, he did not forget those who were less fortunate. Phelps regularly contributed to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, the Colonization Society, the Blind Asylum of New York City, the American Bible Study, and the American Home Missionary Society, and served as President of each one of these organizations at various times. Many other societies and charitable institutions also benefited from him both directly and from his estate. At his funeral, family friend Mrs. Sigourney wrote of Phelps,

“The cares of commerce and the rush of wealth Swept not away his meekness, nor the time To cultivate all household charities; Nor the answering, conscientious zeal To consecrate a portion of his gains To man’s relief and the Redeemer’s cause.”

His grandson, James Stoker, established the Anson G. Phelps Lectures on Early American History at NYU in 1918. There is a collection of pamphlets, brochures, and posters promoting the lectures as well as published lectures and manuscripts on lecture topics at the University covering the series from 1920-2008. The purpose of the lectures, according to Stokes, was that of “inculcating a knowledge of the principles which animated the Puritan Fathers and early colonists; and of the influence they have exerted upon modern civilization.”

The Clocks at Market

The vast variety of Ansonia clocks and the high numbers of those produced have made collecting them something anyone can collect at any level. With a quick scan via Google, there are clocks available for purchase ranging from $35 to $1,500 and up. The determination of value rests on condition, features, working status, and how many of a particular model were created. With the signature of an important clockmaker, look for a higher value.

Related posts: