By Susan Baerwald

In the history of early American culture, there is little specific mention of African American Art. We are aware of some of the early quilts by Harriet Powers, some walking sticks carved by anonymous African American artists, and dolls made by women in their own images for their children to play with. The few pieces we knew were termed “folk art,” or art of the people, which reflected their way of life.

But an entire world of African-American art has emerged that was present in the South – localized and largely unknown to the historians of art until the late twentieth century. This included vernacular pieces by artists who had little or no exposure to the art world. It was not until the seminal show mounted by The Corcoran Gallery in Washington in 1982 entitled “Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980,” that we heard their names and learned about them. William Edmonson, Thornton Dial, William Hawkins, Elijah Pierce, Jesse Aaron, David Butler, Sam Doyle, and more. Twenty black artists were profiled, and 391 works were presented that had been previously unknown to the contemporary art world. The catalogue of the exhibit by Jane Livingston and James Beardsley is out of print but can be found in libraries and museums.

Many of these artists have come to be prized and collected by museums throughout the country, although they have not yet achieved recognition outside the narrow categories of “self-taught,” “naïve,” “visionary,” “vernacular,” or “outsider” labels.

The artist whose sinuous snake was featured on the cover of the catalogue, and who had 36 works in the exhibit has emerged as an artist for whom no labels are necessary, and he is Bill Traylor. His art is extraordinary, and he has come to be known as one of the most important artists discovered in the twentieth century.

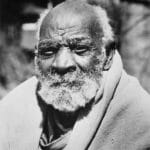

Bill Traylor had an incredible visual imagination that did not become evident until late in life. Born a slave on the George Hartwell Traylor plantation in Benton, Alabama in 1856, Traylor took on the surname of his master, as did his parents, according to the 1900 census. We don’t know much about the young Bill Traylor except that he remained on the plantation after the Civil War ended and continued to work as a farmhand until at least 1937. During that time, he fathered at least twenty children with several wives. By the time Bill Traylor set out on his own in his early eighties, the children had all moved away, and his original wife, Lorissa, had died. He may have worked on a road gang, in construction, and then in a shoe factory. In 1939, he was homeless and received a stipend from a government welfare program. Physical limitations caused by acute rheumatism prevented him from working, but he found his way to Montgomery and made a few friends there who helped look after him.

It is a mystery as to what could have motivated an 83-year-old man, born into slavery, who could not read or write and had no training or exposure to art, to pick up a pencil and a straight-edged stick and start drawing figures on discarded cardboard in the spring of 1939. What is even more amazing is that, from that point, he almost never stopped drawing for the next three years, creating an incredible body of work, estimated at 1,200-1,600 pieces.

His routine was the same each day: after sleeping on a pallet among the caskets at the Ross Clayton Funeral Parlor in Montgomery, Alabama, Bill Traylor situated himself on a box outside on Monroe Street, sandwiched in between a Coca-Cola dispensing machine and a pool hall. An imposing, bearded, heavy-set man nearly six-foot four inches tall, he maneuvered with two canes due to his rheumatism. Once seated, he pulled a crude board on his lap and started to draw, attracting spectators and children from the neighborhood, with whom he chatted occasionally. At some point, Traylor hung the pictures he created on an adjacent fence by looping pieces of string through the tops of the drawings.

As his work became more defined and influenced by the vivid street life he observed in Montgomery, he attracted the attention of a young WPA artist, Charles Shannon, whose eight-year association with Traylor would eventually introduce the former slave’s artwork to the outside world. Shannon recognized the power of Traylor’s images and was intrigued by the strong geometric shapes that portrayed so much movement and life. Traylor’s simplicity and his enormous output impressed Shannon, who encouraged him by bringing him better paper, pencils, and poster paints. Day after day, Shannon returned to watch Traylor work, occasionally talking to him about his images. To this day, most first-hand information about Traylor’s life and work comes from the dialogues he had with Charles Shannon on the street in Montgomery. Frank Maresca and Roger Ricco’s book, “Bill Traylor, His Art, His Life,” 1 contains much of this discourse between Shannon and Traylor, giving us insights into his visual storytelling.

And tell stories he did! Many of his works appear to be influenced by visual memories. Farm animals, which he must have seen during his time on the plantation, are depicted often. Traylor’s acute powers of observation show the relationships between animals, men and animals, human interactions, and domestic and religious gatherings. His renderings connote an exposure to life and his vivid imagination which interpreted those relationships and gave them dimension and texture.

Much of Traylor’s storytelling is about human foibles, particularly man’s relationship with alcoholic beverages. There are many depictions of inebriated men that convey a sense of abandon, especially in how the figures are almost whimsically animated on the paper, as if in a whirl of action. His subject matter included domestic disputes, chases, possum hunts, some nightmarish images, and abstract constructions that may or may not have been inspired by actual images. Whether or not these scenes were imagined or witnessed, they tell distinct stories that resonate with us all.

Likewise, Traylor played with depicting indoor and outdoor space, balancing elements artistically that had no sense of balance in the real world. Tiny men leading large animals, women and men carrying small valises, huge snakes appearing next to abstract forms, men bent over carrying what appear to be large letters on their backs … all of these fanciful images reflect Traylor’s views of the world around him. His sense of composition was extraordinary, and he seemed to use the cardboard shapes he painted on to guide him, sometimes accentuating a flaw or tear in the paper to incorporate it into his story. He had a gift for juxtaposing form and background that reveals a wonderful sense of proportion. His ebullient images capture the essence of the tale he is telling.

Traylor rejected most of the materials that Shannon and others brought him, preferring to work in primary colors, not mixing paints, and rarely overlapping images. His “signature” cobalt blue flat poster paint is extremely powerful because it is spare, yet it still conveys whimsy, energy and emotion. He added cross-hatching and different patterning to many of his works, incorporating details of design that are reminiscent of basket-weaving patterns. Although Bill Traylor never learned to write, someone taught him how to sign his name, and his signature appears on some of his paintings. His social observations are animated, poignant, and express a joy of movement even in the silhouette forms he created. He depicted depth in a unique way, often placing two eyes on the same side of a profiled head, evoking volume and dimension.

Traylor sold some of his drawings to Shannon, who tried to get others interested in Traylor’s art. Some pieces were purchased by passers-by, or some of the people he came into contact with while on the street. Traylor depicted both whites and blacks, and he told Shannon how he distinguished between them. Placing his straight edged stick along the profiles of his drawn characters, Traylor said “Now you see there, when the stick touches the nose and the chin but it doesn’t touch the lips, it’s a white man.”2

Traylor seemed indifferent to the small exposition Shannon mounted of the artist’s works at the New South gallery in Montgomery in 1940. In the program notes, Shannon wrote, “Bill Traylor’s works are completely uninfluenced by our Western culture. Strictly in the folk idiom – they are as unselfconscious and spontaneous as Negro spirituals. He has recorded the life he has known with a boundless imagination that is steeped in a real joy of living.”3

Aside from the Montgomery show, Traylor’s work was not recognized during his lifetime, despite Shannon’s efforts. It was not until the landmark exhibit “Black Folk Art in America” in 1982 at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. that his images came to the attention of the art world. Suddenly, Bill Traylor became a known factor. His amazing output in just three years, from age 83 to 85, wasn’t realized until long after he passed away. In fact, although he died in 1947, there is no evidence that Traylor painted after he left Montgomery in 1942.

Little is known of his travels north during the four years in which he visited some of his children and is said to have encountered some personal difficulties. When he returned to Alabama in 1946, he became ill and lost a leg to gangrene. He never regained the urge to create his art. He died in a nursing home in Montgomery in 1947, at the age of 93.

Today, Traylor is recognized as one of the most prolific, expressive artists of the twentieth century. He is called self-taught, visionary, outsider, primitive artist … among other things. But above all, he is viewed as an artist. The lines are blurring between folk art and contemporary art, and soon there will be no distinctions to separate the art of Bill Traylor from any other contemporary masterpieces of the last century.

Just Folk is a gallery in Summerland, CA, featuring unique artworks whose designs are esthetically-appealing, ordinary things that are invested with extraordinary individuality. Susan Baerwald and Marcy Carsey founded the gallery in 2007 after successful careers in producing television programs. They were both lifelong collectors of American Folk Art and Antiques.

References:

1. Maresca, Frank and Ricco, Roger, “Bill Traylor, His Art-His Life” Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1991

2. Ibid

3. Montgomery (AL). New South Art Center. BILL TRAYLOR – People’s Artist. 1940.

4. Maresca, Frank and Ricco, Roger, “Bill Traylor, His Art-His Life” Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1991

5. Sobel, Mechel, “Painting a Hidden Life: The Art of Bill Traylor,” Louisiana State University Press 2009

Callouts:

“… what could have motivated an 83-year-old man, born into slavery, who could not read or write and had no training or exposure to art, to pick up a pencil and a straight-edged stick and start drawing figures on discarded cardboard in the spring of 1939.”

“Bill Traylor’s works are completely uninfluenced by our Western culture. Strictly in the folk idiom – they are as unselfconscious and spontaneous as Negro spirituals.”

“Charles Shannon recognized the power of Traylor’s images and was intrigued by the strong geometric shapes that portrayed so much movement and life.”

“His social observations are animated, poignant, and express a joy of movement even in the silhouette forms he created.”

“Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor” at the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum from September 28, 2017 – March 17, 2019

WASHINGTON, DC – Bill Traylor is one of the most celebrated American self-taught artists. His drawn and painted imagery embodies the crossroads of multiple worlds: black and white, rural and urban, old and new. His life – which spanned slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow and the Great Migration and foreshadowed the era of Civil Rights – offers a rare perspective to the larger story of America.

“Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor” is the first retrospective ever organized for an artist born into slavery and the most comprehensive look at the Traylor’s work to date. The exhibition, for the first time, will carefully assess Traylor’s stylistic development and interpret his scenes as ongoing narratives rather than isolated events. His layered messages blended common imagery with arcane symbolism and used ambiguity as a means to explore themes of freedom and struggle in the Jim Crow South. His work balances narration and abstraction and reflects both a personal vision and the black culture of his time. Traylor’s astonishing visual record will be acknowledged as an unprecedented and vital chronicle in American art and history, as well as a precursor to the Civil Rights movement.

The exhibition is organized by Leslie Umberger, curator of folk and self-taught art. The museum’s collection includes twelve works by Traylor, six recently acquired, which will be featured in the exhibition. A major book, written by Umberger, is forthcoming. The Smithsonian American Art Museum will be the sole venue for the exhibition. For further information as it becomes available, visit www.si.edu.

Related posts: