The World of Washday Collectibles

by Donald-Brian Johnson

Some folks collect teacups. Or thimbles. Maybe even swizzle sticks. Tiny treasures that are compact, easy to display, and even easier to store.

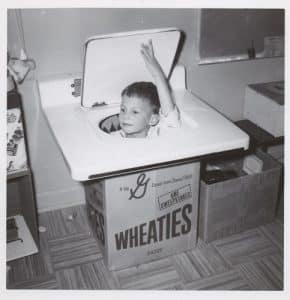

Other folks collect washing machines. And dryers. And washer-dryers. These are definitely not tiny. Displaying (or even storing) them requires a generously-sized (and otherwise empty) basement or garage. But these jumbo collectibles and their colorful accouterments—from clothespin bags to dealer signs, vintage soap boxes to wicker laundry baskets—are cleaning up among today’s collectors.

The reasons? For baby boomers, the answer may be a fond rekindling of childhood memories. For fans of Mid-century Modern, the streamlined design of these machines is a tangible representation of the space-age technology that fueled the 1950s and 60s. For the rest of us, they’re just fun to look at.

Before the advent of the automatic washing machine, a housewife’s lot was not a happy one. Washing and ironing were just the first two of her assigned daily chores. On the list for the rest of the week: sewing, churning, cleaning, and baking. By Saturday night, the weary pioneer woman was more than ready for her final weekly duty: Rest on Sunday.

When we watch an episode of Little House on the Prairie, laundry day seems wonderfully nostalgic – but way back when, “doing the wash” was actually a backbreaking, all-day affair. Prior to the introduction of indoor plumbing, water was hauled from the pump or well and heated over a roaring fire before it was ready for the wash tub. To cut down on pump visits (about 10 per day according to an 1886 survey), the hot soapy water was used until it simply could not be used any more. This meant that baby’s delicates had to be washed first; Dad’s grubby coveralls were saved until the end.

After the soapy scrub, rinsing was required in a tub of clean water. Each sopping item was then rolled and hand-twisted, forcing out excess liquid. Line-drying (hopefully on a warm day with a steady breeze) meant the laundry would be ready, bright and early, for Tuesday’s task (ironing, in case you’ve forgotten).

Primitive? Well actually, this was a step up. In ancient times, just like in all those swords-and-sandals movie epics, clothes were washed in a stream, and beaten against rocks to remove dirt. Seafarers had their own variation: dirty laundry was stuffed in a cloth bag, the bag tied to a rope and thrown overboard. Dragged behind the ship, and agitated by the ocean waves, the clothing emerged after its dunking somewhat cleaner (if saltier).

Coming Clean On Washing Machines

Eventually something had to give (other than the back and patience of the average housewife). As far back as 1691, a patent was issued in England for a “Washing and Wringing Machine,” although few details exist. The earliest well-documented laundry day timesaver, the washboard, made its debut in 1797. No more scraping clothes over river rocks, or scouring with sand!

In the United States, Nathaniel Briggs was granted a 1797 patent for a “Clothes Washing” device, although no records remain of his invention. The first documented “Clothes Washer With Ringer Rolls” was patented by John F. Turnbull of Canada, in 1843.

Tubs with crank-operated paddles meant that laundry could be more easily swirled through soapy water. The first commercially available machine of this type arrived in 1874, courtesy of William Blackstone of Indiana. Legend has it that Blackstone, evidently a true romantic, came up with the invention as a birthday gift for his wife. Blackstone’s wooden “washing machines” retailed for $2.50. Later adaptations utilized metal, rather than wooden tubs, so that a fire could be kept burning below, ensuring continually warm water.

With the dawn of the electric age in the early 1900s, those involved in the budding business of providing industrial products for the home soon saw the light. Ads for the earliest electric washer date as far back as 1904, although Alva J. Fisher’s 1910 patent credits him as the originator of the first one, 1908’s “Thor” (earlier uncredited patents, discovered in recent years, have placed Fisher’s claim in dispute).

By the late 1920s, over 900,000 homes in the United States had electric washers. During the 1930s depths of the Depression, however, that number plummeted to less than 600,000. But as the economy picked up, so did life in the laundry room.

All the Dirt on Automatic Washers

The “automatic” washer combines the two major functions of water-based laundry cleaning: washing the grime from clothing, then extracting the water. Much appreciated extra bonuses: filling the machine, heating the water to a desired level, and draining it after use.

In 1937, Bendix introduced its first automatic washing machine, much like today’s front-loaders in appearance and function. However, with no drum suspension, floor anchors were required; otherwise, the machine “walked” when in use.

Sixty percent of American homes with electricity had electric washers by 1940, but further innovations stalled with the onset of World War II. Research continued, however, and after the war, the automatic entered its days of sudsy glory. The first top-loading automatics came courtesy of Whirlpool and General Electric in 1947. And, while many homemakers still preferred clotheslines in the fresh open air, the electric dryer also made great strides during the late 1940s.

Although on the market since 1915, electric dryers had been costly and inefficient. New and improved versions not only added an exhaust to remove moisture, but also included a cool-down cycle, and front-mounted timer/temperature controls. This was a far cry from the clothes dryer of the 1800s: a laundry-filled vented metal drum, hand-cranked like a barbecue spit over an open fire.

Once simply utilitarian, washers and dryers were now important decorative components of the thoroughly modern home. Homemaking magazines capitalized on this change of focus. Drudgery days were gone! The smiling housewife in appliance ads was exquisitely dressed and carefully coiffed, her washday worries eliminated at the push of a button.

That new arrival, the television, provided visuals of additional must-haves. Consumers wanted their very own Westinghouse “Laundromat,” just like the one extolled by Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz of I Love Lucy fame. When Ozzie & Harriet featured a Hotpoint washer/dryer pair as perfectly matched as the show’s stars, appliance stores were flooded with customers.

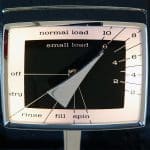

There was always something new on the washday horizon. Futuristic machine control panels adopted the same silvery, space-age stylings popular in autos of the era. The similarities weren’t surprising: some of the best-known appliance brands were actually auto company offshoots, including American Motors’ Kelvinator and General Motors’ Frigidaire brand names. There were also team-ups with detergent manufacturers, giving buyers a little something extra for their money: a brand-new box of Tide, for instance, lurking inside that brand-new washer.

The combination washer-dryer also enjoyed a vogue, although this double-duty machine mashup met with varied success. Maytag voluntarily recalled its washer-dryer combo, produced from 1959-1962, after complaints that the drying power was roughly equivalent to that of a portable hair dryer. Nearly all the returned machines were then destroyed by Maytag; only three are currently known to still exist.

Although early automatics took pride in their pristine whiteness, the 1950s and 60s saw the arrival of appliance colors intended to complement the home environment. Relatively innocuous coppertones and pastel pinks opened the floodgates for shades less appealing to today’s eyes: lurid lavenders and seaweed greens.

Automatic washers and dryers from the late 1940s through the late 1960s, and their accompanying paraphernalia, are what set the hearts of today’s collectors on spin cycle. While most of the best-known vintage machines were U.S.-made, the interest in them is worldwide. Aficionados from locations as disparate as Minneapolis and Trinidad, Russia and Boston, Omaha and Australia, share photos and tips on websites devoted to automatic washers. (Which washers are best for a good scrubbing? Whirlpool and Kenmore. How about for towels? Nothing beats a Frigidaire.)

The ongoing goal is the restoration of these artifacts (as closely as possible) to original operating condition and sparkling showroom appearance. And, even though most washer and dryer collectors are self-taught “garage mechanics,” the restoration process moves along fairly rapidly, ranging from just several weeks to several months.

Often joining in online repair discussions are now-retired service techs, who once worked for the companies manufacturing the machines. Their memories and maintenance hints are invaluable, as are highly sought-after original instruction manuals. “After all,” notes one collector, “if the machines don’t work, they’re pretty much junk.”

Some collectors are interested in any and all automatics and their assorted trappings (soaps, sales displays, ads, laundry room necessities, and so on). Others specialize, collecting machines by a specific manufacturer, those made during a certain time frame, or machines that represent a “first” (for instance, the first top-loading washer, or those that are otherwise unique in design or function). Cross-collectors seek out additional household appliances of the same era, such as toasters and vacuums. There are even Holy Grails: that quickly abandoned, oh-so-rare Maytag washer/dryer combo, and the limited-production Lady Kenmore dryer of the early 1960s. Regular collector gatherings are held, with storage trucks brought in tow – attendees bring along their latest restored acquisitions for a super-sized show-and-tell.

Although calling for a certain degree of mechanical aptitude (and plenty of storage space), collecting automatic washers and dryers offers a fascinating take on mid-twentieth century design. The technological advances that followed World War II exemplify the “can-do” atmosphere of the times. Ingenuity and imagination were at the forefront. These simple-yet-sophisticated everyday housewares provide a valuable window on the past, letting us witness just how that past moved boldly into the future … our present.

Today, China leads the world in the production of automatics. Domestically, many familiar names (Amana, Maytag, Kenmore) are now all under the Whirlpool umbrella. Microprocessors handle the entire washing and drying cycles with supremely predictable efficiency. Soon, even those geysers of gushing soapsuds may be just a

Ah, but does it come in avocado?

Didn’t think so!

Donald-Brian Johnson is the co-author of numerous Schiffer books on design and collectibles, including Postwar Pop, a collection of his columns. He makes do with an apartment washer and dryer. Please address inquiries to: donaldbrian@msn.com

All washday collectibles courtesy of Greg Nunn

For more info on the wonderful world of washers (and dryers, too) check out the collectors’ website: automaticwasher.org

Photos by Donald-Brian Johnson & Hank Kuhlmann