By Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

“The whole 1960s thing was a ten-year running party, which was lovely. It started at the end of the 1950s

and sort of faded a bit when it became muddled with flower power. It was marvelous.” – MQ

Inventive, opinionated, and commercially minded, Dame Barbara Mary Quant (1930-2023) was the most iconic fashion designer of the 1960s. A design and retail pioneer, Quant popularized the looks that defined the “Swinging Sixties,” an era for Quant driven by her desire to advance feminism through fashion.

Quant and her looks were equally popular here in the United States. According to her New York Times obituary, “When [Quant] toured the United States with a new collection, she was greeted like a fifth Beatle; at one point she required police protection.”

Hers was a wild life for a little girl born and brought up in Blackheath, London, the daughter of two Welsh schoolteachers.

Becoming Mary Quant

From a young age, Mary knew she wanted to study fashion, but her parents disapproved. When she received a scholarship to the arts-focused Goldsmiths College (now Goldsmiths, University of London), they reached a compromise: she could attend if she took her degree in art education (she studied illustration).

While at Goldsmiths, Quant met her future husband, the aristocrat Alexander Plunket Greene. After graduating in 1953, she began her professional career as an apprentice at a high-end milliner, Erik of Brook Street. Greene, however, had bigger plans for them both.

According to a history of Quant and her influence on fashion from the 2019 special exhibit at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Six Revolutionary Designs by Mary Quant, “In 1955, Plunket Greene purchased Markham House on the King’s Road in Chelsea, London, an area frequented by the “Chelsea Set”—a group of young artists, film directors, and socialites interested in exploring new ways of living—and dressing. Quant, Plunket Greene, and a friend, lawyer-turned-photographer Archie McNair, opened a restaurant (Alexander’s) in the basement of the new building, and a boutique called Bazaar on the ground floor.”

The different strengths of each partner working together contributed to their long-term success: Quant concentrated on design, Plunket Greene had the entrepreneurial and marketing skills, and McNair brought legal and business sense to the brand. Soon, Bazaar and King’s Road became the epicenter of British fashion, and London the epicenter of the so-called “youthquake,” as Vogue put it at the time.

All Fashion Roads Lead to Bazaar

As provided by the write-up for the V&A exhibit, “Quant initially stocked the shop with outfits she could source on the wholesale market, exploiting the opportunity to offer a new take on women’s style. But she soon became frustrated with the clothes available. Encouraged by the success of what Quant described as a pair of “mad” lounge pajamas that she had designed for Bazaar’s opening (the design featured in Harper’s Bazaar magazine and was later purchased by an American manufacturer), she decided to start stocking the boutique with her own designs.

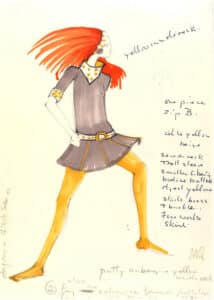

Quant was a self-taught designer, attending evening classes on cutting and adjusting mass-market printed patterns to achieve the looks she was after. Once technically proficient, she initiated a hand-to-mouth production cycle: the day’s sales at Bazaar paid for the cloth that was then made up overnight into new stock for the following day. Although exhausting, this cottage-industry approach meant that the rails at Bazaar were continually refreshed with short runs of new designs, satisfying the customers’ hunger for fresh, unique looks at competitive prices.

Quant’s developing aesthetic was influenced by the dancers, musicians, and Beatnik Street chic of the Chelsea Set, and the Mods (short for “Modernists”), a powerful subculture that helped to define London’s youth culture in late-1950s Britain, with their love of Italian sportswear, sharp tailoring and clean outlines.

Quant’s first collections were strikingly modern in their simplicity, and very wearable. Unlike the more structured clothes still popular with couturiers, Quant wanted “relaxed clothes suited to the actions of normal life”. Pairing short tunic dresses with tights in bright, stand-out colors—scarlet, ginger, prune, and grape—she created a bold, high-fashion version of the practical outfits she’d worn as a child at school and at dance classes.”

By the 1960s, Mary Quant was a global brand, with licenses all over the world and sales that would soon reach $20 million. There was a Mary Quant line at J.C. Penney and boutiques in New York department stores. There was Mary Quant makeup—for women and men—packaged in paint boxes, eyelashes you could buy by the yard, and lingerie, tights, shoes, outerwear, and furs. By the 1970s, there were bed sheets, stationery, paint, housewares, and a Mary Quant doll, Daisy, named for Ms. Quant’s signature daisy logo.Style-Influencing Looks

Emboldened by the acceptance of her design aesthetic, Quant went on to define her coveted status as a designer and advocate for feminism through fashion with such iconic looks as her “wet look” clothes using PVC, the mini skirt, shift dresses, and brightly colored tights. Here are continued excerpts from the V & A’s exhibit highlighting six of Quant’s most revolutionary contributions to fashion and the 1960s:

The Jersey Dress: Of all the fashion revolutions that happened in the 1960s, the boom in knitted jersey fabrics had the most impact on how we dress today. The mini-skirted and modernist silhouettes of the sixties, and the later cling and swing of the seventies, were all—quite literally—shaped by the meteoric rise of jersey. Quant was the figurehead of the jersey dress boom, producing thousands of designs in hundreds of different colors and permutations, including different-shaped collars, sleeves, zips, and buttons, with skirts swishy or straight. Frame-knitted

jersey fabric, or “stockinette,” had been used for the production of underwear and stockings since the 17th century but new synthetic fibers in the design and manufacturing of clothing soon became her go-to option, providing the stretch and structure she required for her distinctive minidresses and simple shifts.

Quant’s jersey dress had a media moment when the designer sported a cream and navy version to receive her OBE from the Queen in November 1966, standing out among the sober-suited crowd. Practical, affordable, crease-resistant, and colorful, the jersey dress became a driving force in the democratization of style.

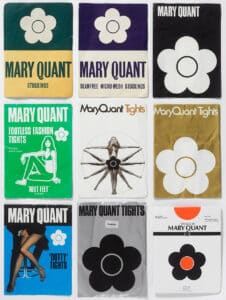

Tights: Sixty years ago, most women were still unquestionably wearing stockings in the shade “American Tan” (black stockings were a hangover from the Victorian era). Held up by garters or attached to a separate suspender belt with hard metal clips, stockings were fiddly and uncomfortable to wear. Quant, always looking to develop new ideas, wanted stockings and tights to be comfortable and stand out as a fashion statement, introducing tights in such colors as bright mustard yellow, ginger, and prune, as well as black – the perfect accompaniment to her knee-skimming skirts and dresses which enabled women to dance, run and move. She partnered with the Nylon Hosiery Company to develop a technique of making long stockings that joined together at the top and were specially dyed to contrast and coordinate with Mary Quant separates. The partnership proved to be long-lived, with an ever-expanding range of new colors and patterned knits added over the years. The distinctive Mary Quant packaging, with its instantly recognizable daisy logo, helped her products to stand out among competitors.

Trousers for women: When Quant opened her famous boutique, Bazaar, in London’s Chelsea in 1955, trousers and jeans were popular with female students and sub-cultures on the outskirts of mainstream fashion; however, most women still only wore trousers at very informal occasions or in private. Quant moved the fashion forward and the public when she introduced the “spotty pajamas-style” cropped trouser look. She expanded on that look in her collections from the early to mid-sixties, which featured breeches, knickerbockers (men’s baggy-kneed trousers popular in the early 20th century), dungarees and fashionable trousers worn with midriff-bearing tops or oversized sweaters.

Quant’s daisy motif hot pant outfit.

Appropriating trousers for women remained a strong theme throughout Quant’s career. Towards the end of the sixties, Quant’s range of trousers provided a useful alternative for those who felt uncomfortable wearing increasingly short skirts. Quant was a great advocate of wearing trousers for all occasions and was often photographed in masculine styles, helping to popularize an increasingly informal, androgynous style.

The skinny-rib sweater: In the 1950s, aspiring Beatniks (a fashionable subculture associated with art and poetry) had borrowed men’s sweaters to achieve a loose, sack-like silhouette. But the tweed shift dresses and pinafores that retailed in Bazaar required a different look. As with many of Quant’s designs, the inspiration for the skinny-rib came from childrenswear. In her 1966 autobiography, she describes how she “pulled on an eight-year-old boy’s sweater for fun” and was “enchanted” with the result. Six months later, Quant had put the skinny-rib into production, and “all the birds were wearing the skinny ribs,” which paired perfectly with pinafores, and with a matching woven check jacket and skirt to create a more relaxed version of business dress.

Since the ‘60s, the skinny-rib sweater has retreated and returned as a practical way of adding contrasting color to a winter outfit.

PVC Rainwear: In the 1960s, Quant was “bewitched” by polyvinyl chloride (PVC), “this super shiny man-made stuff and its shrieking colors … its gleaming licorice black, white, and ginger,” Quant wrote in her 1966 autobiography. Quant launched her Wet Collection in April 1963 in Paris, featuring entirely PVC garments. The show was attended by influential fashion editors, and it earned the designer her first magazine cover for British Vogue, featuring a brilliant-red PVC rain mac. The line’s bright new range of waterproofs in primary colors, under a collaboration with British manufacturer Alligator Rainwear, combined functionality with striking visual effects – capes, zips, and contrasting collars and cuffs. These space-age garments were an immediate success.

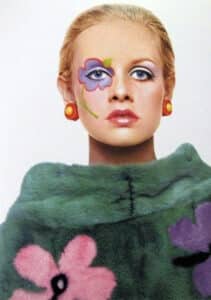

wearing a Mary Quant

creation features Quant’s signature flower design and graced the cover of Vogue.

Loungewear and hotpants: Writing in 2012, Quant recalled how she discovered the “house-wear” market in the US around 1965 and decided to bring this new concept to Europe. She designed “a collection of jersey tops and hotpants in striped jersey-knit fabrics with matching bras, pants, socks, leg warmers and minis – all using knitted fabrics of various thicknesses and weights”. The idea of special clothes for lounging in at home was quite a change in mindset for most of the British public – who only had the ubiquitous dressing gown until then. The range included brightly colored jersey and stretch-toweled one-piece suits, with short zip-up versions and full-length styles that included feet. These easy-to-wear garments were the ultimate in comfort and freedom, made in the fun colors that were at the heart of Quant’s brand. Quant’s experiments with loungewear can be seen as the forerunner to the contemporary ‘onesie’ craze.

Parting Thoughts

Quant passed away in 2023 at the age of 93 but lived long enough to see a new generation of fashion designers and vintage enthusiasts revive and update her Swinging Sixties style.

Today, Quant’s clothes and accessories from that era can be found on such resale sites as 1stdibs, The RealReal, and eBay, where items range in price from under $100 to well over $1,000 and include everything from PVC multicolored rainwear to slip style day dresses and injection-molded “Quant Afoot” plastic booties.

In her eulogy, UK supermodel Twiggy said of the late queen of Britain’s Swinging Sixties fashion, “[Quant] revolutionized fashion and was a brilliant female entrepreneur. The 1960s would have never been the same without her.”

Related posts: