Story by Donald-Brian Johnson – Photos by Leslie Piña

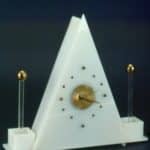

Once seen, never forgotten – that’s a Moss lamp! These Plexiglas marvels first cast their unique glow on households of the 1950s, and have delighted collectors ever since. Perhaps that’s because there’s such a variety to choose from. Many Moss lamps come equipped with spinning figurines and spun glass shades. Others incorporate clocks, radios, music boxes, fountains, and even intercoms into their design. For the truly adventurous, there are Moss room divider, Moss coffee tables, Moss wall plaques, cigarette lighters, bars and aquariums. Each lights up, each uses Plexiglas(r) as its primary material – and each is, as a 1958 Moss ad boasted, “truly a conversation piece.”

Moss lamps were a product born of necessity. In 1937, Gerald “Gerry” Moss founded San Francisco’s Moss Manufacturing Company, after previous experience as a lamp wholesaler. When the wholesale building burnt down, Mr. Moss had two options: go into manufacturing, or go out of business. He chose the former.

The first Moss lamps were traditional ones, metal-stemmed with fabric shades, intended to blend into, rather than dominate, home decor. Then, World War II intervened. With steel at a premium, luxuries such as metal lamps were given low priority. Forced to come up with a new raw material for the company’s products, Gerry Moss turned to staff designer Duke Smith. Smith had the answer: Plexiglas.

Dubbed “plastic” in the Moss literature, Plexiglas (“plexi”) was an acrylic product developed in 1934 by the Rohm & Haas Company. For Moss Manufacturing, Plexiglas had several points in its favor: it was inexpensive, no other company was using it – and most importantly, Plexiglas was not rationed. Lamp production at Moss could continue, although now with an entirely new focus.

Encouraged by postwar sales of Plexiglas lamps, Gerry Moss knew that all his company needed for even greater success was a driving force, capable of working with, and inspiring, staff designers. And what better choice than his wife, the energetic and creative Thelma Moss? By 1950, Mrs. Moss was already an established entrepreneur, owning sixteen Mode O’Day women’s wear shops throughout California.

Contemporaries recall Thelma Moss as a dynamo. Noted one, “her mind could go in one hundred different directions at the same time.” Working closely with talented designers Duke Smith, and later John Disney, Mrs. Moss let her imagination run rampant – and what Thelma imagined, her designers brought to life.

As stylish and colorful as her lamps, Thelma Moss made the most of every new opportunity. Noting the attention attracted when she made Moss factory rounds accompanied by her poodle, Terry, she soon incorporated him (decked out in horn-rimmed glasses) into company promotional photos. When a plexi champagne fountain, designed for the 1956 wedding of her daughter Carol, proved a hit, fountain lamps quickly joined the Moss line. Thelma’s ingenuity, coupled with Gerry’s merchandising know-how, even led to Moss sponsorship of an early ’50s TV show, “Stairway to Stardom,” with contestants and celebrity guests ranging from Rudy Vallee to Hilo Hattie, receiving Moss plexi products for their participation.

Faced with this unusual approach to home lighting, other lamp manufacturers of the period were somewhat bemused. Says Sid Bass of Rembrandt Lamps, “when they first came out, we laughed and said ‘that isn’t going to go.’ But we were wrong.”

Moss lamps were sold primarily through furniture dealers, with new models introduced at each season’s market shows. Dealers would order from a prototype, with actual production then based on the number of orders placed. If a particular model attracted no orders, it was either revamped for a future show, or sold as one-of-a-kind. That production flexibility means that there are well over 1,000 different models in the complete Moss inventory. Fortunately, many of these were captured in photos taken for assembly purposes. While some may never be seen again, others proved very popular. #2293 for instance, a fluorescent-tubed floor lamp dubbed the “Leaning Lena” because of its angled stem, was a best-seller. Because “Lena” remained part of the Moss line for every year of production, examples turn up frequently on today’s secondary market.

Moss lamps were expensive for their time. Original table lamp prices ranged from $29.95 to $79.95, with floor lamps averaging $120-150. By comparison, high-end designer lamps by other companies were being advertised at “$40 the pair”. Still, despite their pricetags, Moss lamps proved popular. Previously, furniture dealers had to sweeten customer deals on expensive items, such as sofas, by “throwing in” lamps or other accent pieces. With Moss, that tradition went out the window. As one dealer remarked in a letter to the company, “with your lamps, we usually end up throwing in the sofa!”

As a general rule, collectors can be quite confident that if a lamp is made of Plexiglas, it was made by Moss. Other extravagant lamp designs of the 1950s utilized plaster, wood, and metal, but when it came to Plexiglas, Moss had the field to itself. In fact, by the early 1950s Moss Manufacturing was the largest user of Rohm & Haas Plexiglas in the United States.

The Shades:

Although Moss also made use of fabric shades, those of “spun glass” were a company trademark. No other manufacturer was able to duplicate the Moss spun glass shade, and the company guarded its shade formula closely. Ingredients were ordered from different suppliers and combined secretly at the Moss factory.

Spun glass is much like the “angel hair” used in holiday decorating. Workers would place spun glass in sheet metal shade molds, then coat it with the Moss secret adhesive formula to create a hard shell. After curing, says Jerry Slater, former Moss General Manager, completed shades would “pop right out like cookies from a pan.”

Because spun glass was surprisingly lightweight, it was possible to create oversize shades with little interior support. Some Moss floor lamps have shades that are nearly 30 inches square. An added benefit: the consistency of spun glass is such that light filters through the shade, casting an attractive glow on the lamp and its surroundings.

The Spinners:

Mention “Moss Lamps” and you may get a puzzled reaction. Mention “the lamps that spin” and recognition dawns. Although not all Moss lamps feature figurines on rotating platforms, those that do leave a lasting impression. And, like the spun glass shades and Plexiglas bodies, rotating figurines are a Moss-only trademark.

Moss lamps produced during, and just after, World War II were non-figural Plexiglas. With the 1950 arrival of Thelma Moss and John Disney, platforms with hidden motors were incorporated into the lamps, and ceramic figurines, with pins running up through their bases, were attached to the platforms. When the correct switch was thrown, each figure began its sedate spin.

Plexiglas means Moss, spun glass shades mean Moss, figurines often mean Moss-but perhaps more than any other indicator, this one holds true: if it spins, it’s definitely Moss.

As Moss spinner lamps increased in popularity, the firm’s designers moved on to the next question: if a lamp could spin, what else could it do? The answer was “just about anything.” Beginning in the mid-1950s, there were Moss Music Box Lamps, each featuring a “Golden Tone Music Box.” A pull of the chain, and tinkling standards of the day delighted the listener. Moss radio lamps kept entertainment close at hand, and intercom lamps provided room-to-room communication. Clock lamps ranged from clock table lamps to clock room dividers, grandfather clock lamps, and even a clock coffee table.

Bursting with ingenuity, the Moss designers also came up with fountains, waterwheels, and aquariums, each equipped with its own functioning Moss lamp. The wonders reached their zenith with the “Fish Tank Bar”, which combined the functions of a lamp, aquarium, and bar, all in one unit. Originally retailing for $199.75, the “Fish Tank Bar” can, if hooked today, net more than $2,400.

Vintage Moss lamps are now in their golden years, and with age comes attendant problems. Most common among these are yellowy Plexiglas (the result of too many smoke-filled evenings in 1950s living rooms), drooping, shaggy, shades, and spun-out spin motors.

- For discolored Plexiglas, the solution is simply to apply a mixture of mild soap and water with a soft cloth. If the film proves stubborn, alternate wiping with a damp cloth, then a dry cloth, and keep repeating until the surface shines. Do not use any abrasives, as they will scratch the Plexiglas, or glass cleaners containing ammonia or alcohol, as these will eventually craze or cloud the surface.

- As for Moss spun glass shades, many now look in desperate need of a haircut. Prolonged exposure to bulb heat over the years has caused the spun glass fibers to come loose from the adhesive. Some collectors recommend a brush application of water-based glue or acrylic gel medium. Others report success with a hand-smoothed application of spray starch.

- For noisy or non-functioning spinner motors, original Moss replacements are unfortunately no longer readily available. The best option here is to check at a clock shop for similar motors, which often prove workable substitutes. Attention to restoration and repair will not only add to a lamp’s value, but will also present it in its best light-as a brilliant design icon of an earlier age.

After World War II, in the invigorating anything-goes world of modern design, Moss lamps fit right in. But as the 1950s edged into the 1960s, and unified decor schemes became popular, consumer interest shifted to lamps that were lamps, rather than “conversation pieces.” A 6-foot Plexiglas floor lamp decked out with a 30-inch spun glass shade and a spinning figurine was no longer the ideal addition to a suburban home. It just didn’t blend. Moss tried to recapture public interest in the mid-1960s with its Tami line of traditional ceramic-based lamps, but by 1968 buyers were in short supply. Lamp production ceased, and Moss Manufacturing became Moss Lighting, a successful distributor of European fine lamps. Gerry Moss died in 1992, and Moss Lighting remained open until the retirement of Thelma Moss in 1997.

Today, the bold design choices and whimsical charm of Moss lamps continue to attract collectors and inspire modern designers. Although admittedly not for every décor, in the right environment Moss lamps are just as the ads promised – sure-fire conversation pieces! Moss lamps have even become part of pop culture, providing background atmosphere in such films as “From Here To Eternity” and “To Wong Foo, Thanks For Everything, Julie Newmar.” For the lamps that spin, popular taste has spun full circle.

Donald-Brian Johnson (text) and Leslie Piña (photos) are co-authors of numerous books on mid-twentieth century design, including “Moss Lamps: Lighting the ’50s.”

Related posts: