by Judy Gonyeau, managing editor

Imagine being the only black child in your school who is striving to enter the field of architecture. You have no parents to support you, and even one of your teachers advises you not to go into the field because of your race. Imagine doing that anyway, and not just surviving, succeeding.

That is what happened to a strong, confident, astute, gifted, and determined young man named Paul Revere Williams (1894-1980).

A Shattered Childhood

Paul Williams was born in Los Angeles in 1894, just after his parents, Chester and Lila, along with Chester Jr., moved there from Tennessee because they had tuberculosis and heard the weather in LA would be better for their health. At that time, California was looking to capitalize on its weather and fertile lands and encourage people to come west, knowing that if there were more people and a desire to travel west, the railroad would come west, too.

Unfortunately, just two years later Paul’s father passed away, and two years after that, his mother did as well. Chester, Jr., at just 13 years old, was not old enough to handle all the responsibilities, and the two boys were sent to live in separate foster homes and tried to keep in touch, but that was not easy and they drifted apart. Chester, Jr. sold fruit along the Old Town Plaza in downtown LA but ended up getting pneumonia in his early 20s, and died.

At this point, Paul was taken in by Charles and Emily Clarkson, and was now being raised in the first secure, loving household since his birth. Emily saw something in Paul and encouraged him to become whatever he wanted and helped to provide him with the best education to support his dreams.

Because of where they lived, getting a good education appeared to be more than just possible in this joyous Black community that had minimal threats of violence and discrimination. Here, they could own land and open businesses, and walk comfortably about the town. The schools were predominantly white, but Paul excelled, nonetheless. Despite a few comments from friends, neighbors, and his teachers, who discouraged him from becoming an architect—“Your own people can’t afford you, and white clients won’t hire you,” and “Who ever heard of a black architect?”—Paul attended the Los Angeles Polytechnic High School, the first nonprofit, independent school in Southern California, followed by the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design. He was certified as an architect in 1915. Pursuing his dream, Williams worked hard to make Emily Clarkson proud.

Coming of Age

Williams continued his education at the University of Southern California, where he studied architectural engineering, and took low-paying jobs at a few architectural firms to further his education. He also met Della Mae Givens at a church youth group, and they later married. She ran the home and their assets, and he was free to build his skill set and pursue his career.

According to Britannica.com, “He learned about landscape architecture while working with Wilbur D. Cook and got his first taste of designing on a palatial scale at the firm of Reginald D. Johnson. From 1920 to 1922 he worked for John C. Austin (with whom he later collaborated), turning his attention to designs for large public buildings.”

Another skill Williams worked on and perfected was his ability to draw upside-down, mainly because he would not be allowed to sit next to his clients without risking making them feel uncomfortable. Aware of how they felt, working this way allowed him to face clients and make his presentation without having to invade their personal space. Williams was astutely aware of how people may have perceived him just because of his skin color and was determined to keep everyone comfortable when working on their project. He also learned to listen carefully and asked a lot of questions in order to exceed their expectations.

At the age of 27, Williams attained his California License to Practice Architecture and one year later opened his own business, Paul R. Williams and Associates. Also at 27, Williams attained a seat on the Los Angeles City Planning Commission – a feat that was hardly ever bestowed to one so young. At 28, he became the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects. He was on his way.

Catching That Break

The great city of Los Angeles was growing by leaps and bounds, with plenty of work for builders, designers, contractors, and architects. As architecturaldigest.com put it in an article about Williams, “California was developing its identity. Post-Gold Rush, between two world wars, giving birth to Hollywood, and in the midst of the Great Migration; the state was molding its modern personality and morphing from rural and expansive farmland into homesteads, metropolises, and industries.”

Williams was in the right place at the right time. However, from early on, he encountered discrimination wherever he went to work, and he worked in just about every aspect of architecture he could. Furniture construction, as an apprentice to architects, working for contractors – any “in” he could figure out to get him to where he wanted to be.

He also entered design competitions to get his work seen without factoring in the color of his skin. He won many, and this brought him the attention of area architects. One architect became a mentor to Williams, residential architect Reginald Johnson, who brought Williams into his circle of professionals and friends – his very popular and well-known friends. But it was a customer who bought newspapers from him when he was a newsboy who sought him out for that big break: Flintridge.

Former Senator Frank Flint was creating a suburban community called Flintridge just north of LA. Having remembered the clever newspaper boy from years ago, and having followed his career, Flint hired Williams to create his home, leading to the creation of dozens of other homes in the area. Williams’s portfolio was growing exponentially across L.A. county. His expertise in and knowledge of what it meant to be able to create luxury homes for the film industry’s titans furthered his fame as an architect.

Because Williams knew all aspects of creating a home—from designing and making furniture to placement of art, and the sourcing of elegant fixtures and accessories for the home, he was given the moniker of “master of creative eclecticism” from one of his employees. His level of taste for elegant design on both the exterior and interior of the home made him the one who truly created the “lifestyle of the rich and famous” in L.A. William’s ability to imagine what this new lifestyle would be that brought in the quality

Homes of the Rich and Famous

Horse Trader Jack Atkin sought out Paul Williams to create a home that was ostentatious, and proud to be that way. The Depression was in full swing, but Atkin had money to spare, it seemed. He wanted a home of splendor overlooking Pasadena that would set him well above the others in his “set” of cronies in terms of content and cost.

Upon boasting to his group that he was designing a house costing half a million dollars, he asked Williams to add another $150,000 to the house when the bill came to only $350,000. Five hundred thousand dollars back then would be over $8.5 million today.

The Atkin home was used in several films such as the original Topper; episodes of Murder, She Wrote; one of the Rocky films, and many others. Atkins would rent it out for movie-making as a charity, giving the money to area food banks.

The Depression did not mean homes were not being built. In fact, Williams designed over one hundred homes during this time for the likes of Tyrone Power, Lon Chaney, and Bert Lahr. Even though he would not have been allowed to live there himself, Williams approached each home project with the mission to exceed his client’s expectations. Moving into the 1940s and 50s, Williams would go on to design homes for Lucille Ball, Frank Sinatra, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Cary Grant, Anthony Quinn, and many more.

For the Corporate World

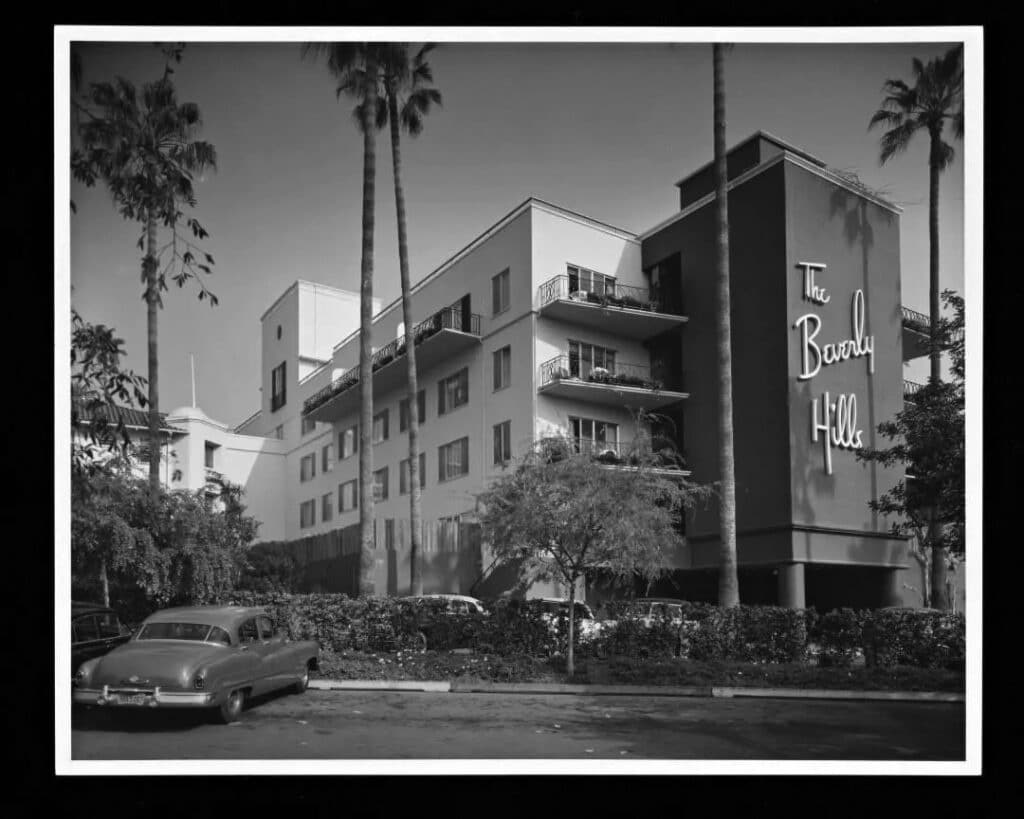

As Williams’ reputation continued to climb, he took time to focus on creating a working space for a variety of corporate clients. In 1938, Jules Stein asked Williams to design the Music Corporation of America building (see column header). The building itself resembles a large Georgian home in the center of downtown Beverly Hills. Now placed on the Beverly Hills Register of Historic Properties, the original mission was to give the atmosphere and space to provide comfort and space to encourage creativity. In 1964, the building was taken over by defense contractor Litton Industries, and the new owners reached out to Williams to construct a second, larger three-story addition.

This store featured incredible interiors designed to keep the customer comfortable.

Another renowned building designed by Williams is Beverly Hills Saks Fifth Avenue. This is an example of Williams’s ability to meld the Southern California style façade with his design aesthetic as it applied to home interiors. His design blew customers away, instantly making them more comfortable while shopping in a luxuriant space meant to make the merchandise shown in its best light.

Other famous non-residential landmarks he designed in and around L.A. include the Second Baptist Church of L.A., Chasen’s Restaurant, Arrowhead Springs Hotel, and work he did for the Naval Air Station in Long Beach.

For the Average (G.I.) Joe and More

Photos by architectural photographer and author of Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View, Janna Ireland.

Once established, Williams turned to his own race and worked on projects to lift up the Black community. He made buildings that continued to reflect his design aesthetic to everyone – not just the rich and famous.

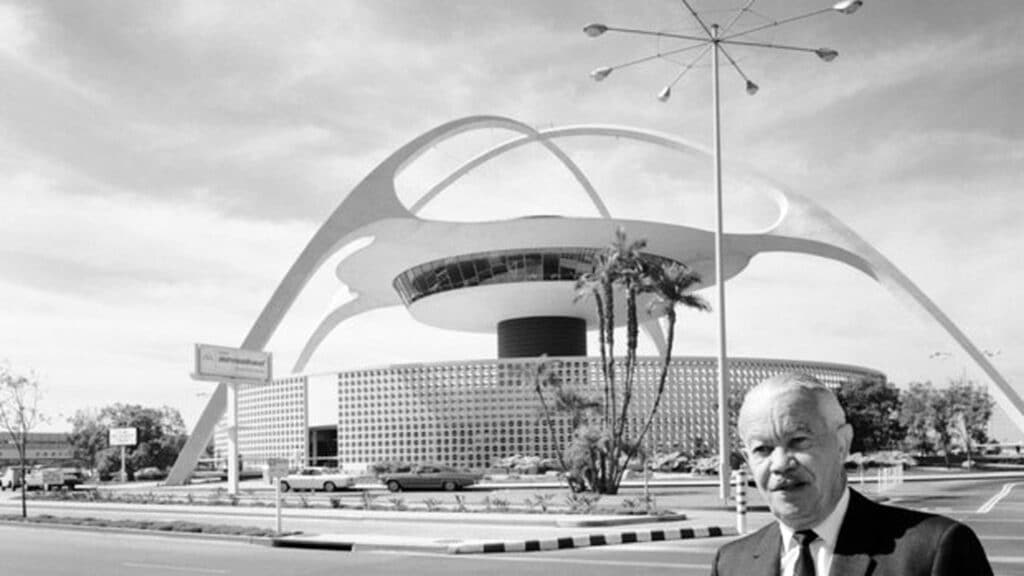

After World War II, he designed affordable tract housing for Black veterans returning home. According to a segment on NPR’s All Things Considered, he helped design “iconic public and commercial buildings, including the Los Angeles County Mosk Courthouse, the historic Spanish-colonial style YMCA building in downtown LA, and part of the LA International Airport.” Other buildings included banks, churches, and other residential sites in predominately Black neighborhoods.

He Wrote the Book On It

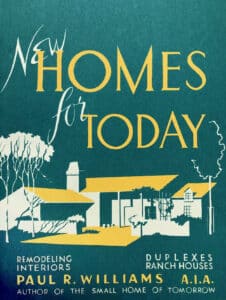

In his book New Homes for Today, Williams answered the question “Can we afford an architect?” with “To this question, there is only one answer: You cannot afford to build a home without an architect.”

New Homes for Today by Paul R. Williams, A.I.A., 1946. In this book, Williams appears to focus on homes for the middle-class homeowner. According to Rush Dixon Architects, “the structure of the book itself allows just two pages for each house design and includes the description, floor plan, and classic-now-vintage perspective renderings. Home names paint a picture of each home’s character. Our favorite is ‘The Esquire,’ a 2-bedroom house totaling 1,260sf with a large living room opening to a side patio and a couple of fireplaces – one indoor and one outdoor.”

Further in the book he shared some advice:

• DO arrange the rooms so that passage may be made from one part of the house to another without the necessity of going through the living room.

• DON’T plan the entrance door to expose all of the living room every time the door is opened.

• ANTIQUES can be mixed with modern pieces, but it is a job for the expert rather than the amateur decorator.

A Fitting Tribute

Forty-one years following Williams’s death in January 1980, an article in the Los Angeles Times, by columnist Carolina A. Miranda, presented Williams and his work to the public on the front page, where such notice would have appeared if he passed today.

Pioneer of the L.A. look: Paul R. Williams wasn’t just “architect to the stars,” he shaped the city.

Buried beneath a weather report and an investigation into a regional planning commissioner, a brief news item appeared in The Times about the death on Jan. 23, 1980, of architect Paul Revere Williams at the age of 85.

Three days later, the paper ran an obituary. That report was a bit more complete. It featured a photograph of Williams and ran through a handful of his achievements … Yet his death was not treated as big news. The modest obituary ran on page 22.

In the immediate wake of Williams’ death, no glossy books of his work were published, much less a catalog raisonné. Buildings he designed were torn down; others were remodeled beyond recognition. The work of an architect whose firm was responsible for thousands of structures in Southern California, who was name-checked in real estate ads as “world-famous,” who shaped L.A. through civic roles … was in danger of fading away

How times have changed.

In 2017, the AIA posthumously awarded Williams its prestigious Gold Medal. Last February, PBS aired the documentary, Hollywood’s Architect: The Paul R. Williams Story. In the fall, artist Janna Ireland published the elegant photographic collection Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View.

Most significantly, last summer, USC and the Getty Research Institute announced that they had jointly acquired Williams’ archive – a trove of approximately 35,000 architectural plans and 10,000 original drawings, in addition to blueprints, hand-colored renderings, vintage photographs, and correspondence. The acquisition will, for the first time, allow public access to the breadth of the architect’s work.

To learn more about Paul Revere Williams, check out these videos available to view at our online Video Gallery