The Art of Buying Cheap – Business of Doing Business – The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles – March 2003

by Ed Welch

No dealer has ever made one cent selling anything. The selling process is expensive, it is negative cash flow, and it wastes your time and energy. The simple fact is that selling takes money out of your pocket.

Dealers make all their profit in the buying process. If you, as a dealer, want to make more money, hone your buying techniques. This is where the profits are.

If a dealer pays too much to buy an antique, that dealer cannot make a profit. The dealer may be able to resell the overpriced item for more money than he or she paid. But if the money gained does not equal at least 60 percent of the purchase price, that dealer will suffer a financial loss on that item.

The break-even figure of 60 percent is arrived at by calculating selling expenses, which average 20 percent in the trade, income taxes which average 18 to 22 percent, and buying expenses which average between 8 and 12 percent. The bottom-line is: If you want to make money, buy cheap!

The one exception to the “Buy Cheap Rule” is when a dealer has a chance to buy the very best example of an antique or collectible. Generally, the best examples sell between three and five times the price of a common example. A few best examples sell for as much as a hundred times the value of a common example. It is nearly impossible to lose money overpaying for the best. The demand for such items is so great that the item will resell quickly at the new higher price.

This is part of my assembled lot of signed country furniture. All chairs are signed by the makers. Signatures include Corey, Danforth, Gaines, Dunkin, Wiggins, Dodge and several others. Age is from 1760 to 1930. All chairs are useable, several need re-caning and three need to be re-glued.

Unfortunately, there are too few “best examples” for sale in today’s antique marketplace. Dealers must ‘make do’ buying and selling common examples. Common examples are hard to sell. The only time that common examples sell quickly is when the price is lower than the average selling price. If you want your common merchandise to sell quickly, you must buy cheap and price cheap.

There are many ways to buy cheap. One method, understood by most dealers, is to buy in lots. It is nearly impossible to lose money buying entire collections. A dealer willing to purchase the contents of a home or business, or hundreds (preferably thousands) of like items, has the best opportunity to make real profits. The advantage of buying in large lots is that each item has a lower cost compared to a similar item sold individually.

The horses are part of my Junk Art collection. The horse in Ballerina Pose was bought in a flea market in Maine. The Venice Horse was purchased at auction. The bronze head reminds me of a painting (“The Scream”) by Edvard Munch. I bought it in Los Angles at a flea market.

Eight years ago, a dealer at Brimfield offered to sell 1,000 pairs of never-used mid-1800s eyeglasses for $10 each. At the time, such frames sold for $22 each. I declined because the $12,000 markup was not enough to allow a profit on a $10,000 purchase once tax, selling overhead, advertising, and years of storage were considered.

I made a counter offer of $3,000 under the following conditions: The original offer was made on Tuesday, the first day of Brimfield. I knew that the dealer changed fields four times during the week. My offer was that I would buy the frames on Friday if he were unable to get a better price. I did buy the lot on Friday.

I have less than one hundred of these eyeglasses still in stock. The history of my selling prices is $22, $28, $35, $42, and $47. Although I have spent more than the purchase price ($3,000) in advertising these frames, I will make a substantial profit on this purchase. This is possible because the selling price has gone up over the years and because I considered marketing expenses before I made the purchase.

Because buying in quantity is profitable, many antiques dealers use creative buying methods to assemble lots. Some dealers treat all items purchased on a buying trip (Brimfield, for example), or auction, as being a “lot.”

Last fall I attended an auction that advertised many medical and related antiques. The first medical item to come up for sale was a rare medical container. I knew with certainty that I could resell this item for $1,200. My “stop-bid price,” noted in my catalog, was $600. The auctioneer tried to open the bidding at $200, lowered the asking price to $100, $50, and finally to $25. I bid the $25 and no one bid against me.

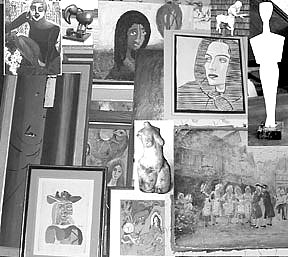

This collage does not represent a true cross-section of my lot of junk paintings. It contains too many modern works. Most of my primitives and landscapes are stored in a warehouse away from my home. Two of the prints are signed by the artist. The upper-right image is part of the original backdrop for the Broadway show “Cats.” The painting at the lower right is signed by the artist. It is of a street scene in Quebec in which church-sponsored maidens from France are introduced to prospective husbands by Catholic nuns. Unlike the English, who settled the Colonies as families, Quebec was settled by men who intended to make their fortunes and return to France. The Catholic Church, in an attempt to discourage French men from taking Indian wives, imported middle- and upper-class women for arranged marriages.

When I am lucky enough to buy a sleeper early in an auction, I consider myself to be ahead of the house. Therefore, I am willing to give back to the house a portion of the money I saved. I do this by adding plus signs (+) after my stop-bid prices. One (+) is my signal to bid one bid over my stop bid price. Two (+ +) is my signal to bid two bids more than my stop bid price.

Theoretically, this bidding scheme will allow me to buy more antiques without spending more money than I originally planned. I was successful in buying 36 items. Twenty-nine of these items were purchased below my stop-bid figures. The seven items that exceeded my stop-bid figures did so in the amount of $1,620. However, I was ahead of the house more than this amount. The total amount of money I paid to this auction house was less than the total of my “stop-bid prices.”

I was willing to overpay for some items because they were of high quality. By treating all items purchased at this auction as a lot, I was able to buy more merchandise while keeping my overall purchase price low enough to make the profit I require to operate a viable business.

Another method of assembling lots is to buy and store single items until you create a lot. I learned this buying trick from a New Hope, Penn., dealer who set up in the booth next to me at Brimfield. At every show, this dealer had a different lot of furniture. At one show he had nearly 100 tables, at the next show his display consisted of more than 60 chests of drawers, and at the next show he had chairs and sets of chairs.

His buying method was simple. He bought every table he could find with a purchase price less than $100. He disregarded age and style. He looked for sturdy useable tables that required a minimal amount of work on his part. He would clean and polish but avoided tables that required stripping and refinishing.

When he had purchased enough tables for a show, he sorted the tables into three groups: good, better, and best. He sorted based only on eye appeal, disregarding age and style; he priced the “good” tables between $200 and $350 each. The “better” tables were priced between $400 and $500 each. The “best” tables were priced between $500 and $1,000.

His display at Brimfield was impressive. He stacked the tables one upon another in groupings of good, better, and best. At the front of his booth, he had three pedestals, one slightly higher than the next. On these he placed three tables: good, better, best. It was easy for anyone to see the difference between his $200 table and his $1,000 table.

I watched with amazement as his more expensive pieces sold first.After several shows, I decided to give his system a try. My first attempt was with country cupboards in original paint followed by dry sinks, oak commodes, thumb back chairs, and State of Maine Chests. Twenty years later, I am still using a modified version of the New Hope System. My current projects are signed pieces of American country furniture and Junk Art.

I have in my warehouse one country chest of drawers, a set of four stacking blanket boxes, two other storage boxes, a nesting set of six pantry boxes, and 27 signed chairs, two of which are Windsors. My requirement for this assembled lot is that all the pieces be signed by the makers.

My Junk Art lot now numbers nearly 300 items. My goal is 600 pieces, enough for my own specialty auction. This has been a fun lot to assemble. I disregard age, artistic style, medium, and signatures. I will buy sculpture, carvings, folk art, paintings, drawings, prints and photographs. My requirements for this assembled lot are a cost of $25 or less and that I personally like the work.

This is my second attempt at Junk Art. My first attempt, in 1984, was not as profitable as I would have liked. I consigned the entire lot to auction. My selling expense was 20 percent of the selling price. Overhead is figured as a percentage of the purchase price. No dealer can stay in business with a selling overhead equal to 20 percent of the selling price. I will not make that mistake again.

Related posts: