How Creativity Drives Desire: Exploring the Neural Mechanisms of Creativity and How they Relate to Collecting

by Shirley M. Mueller, M.D.

Creativity is not just for artists—it’s present in solving problems, making jokes, or even collecting objects. The process of collecting activates a variety of brain networks that are vital to creativity. Attraction to an object is mediated in the brain by memory, aesthetics, salience, and reward anticipation.

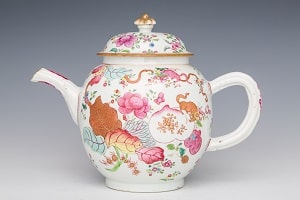

If you’ve ever looked at a curio cabinet stuffed with antique snuff bottles, taxidermied birds, or 18th-century teapots and thought, “Yes, this is my aesthetic,” you’ve experienced the brain’s creativity engine at work. Whether you’re a collector of the exquisite or the eccentric or something more common, the psychological spark behind why you find these objects meaningful is intimately tied to the brain’s structural design for creativity.

What is creativity? How is it wired into our brains, whether we are collectors or creators? To explore this, we need to examine this using a diverse approach including neuroscience, psychology, and a touch of neuroeconomics.

Creativity Is Not Just for Artists

Creativity is often defined as the ability to generate novel and valuable ideas or products. While we associate this ability with artists and writers, neuroscientists now argue that creativity is a universal cognitive function present when we solve problems, make jokes, or, yes, decide which Chinese export teapot is a must-have.

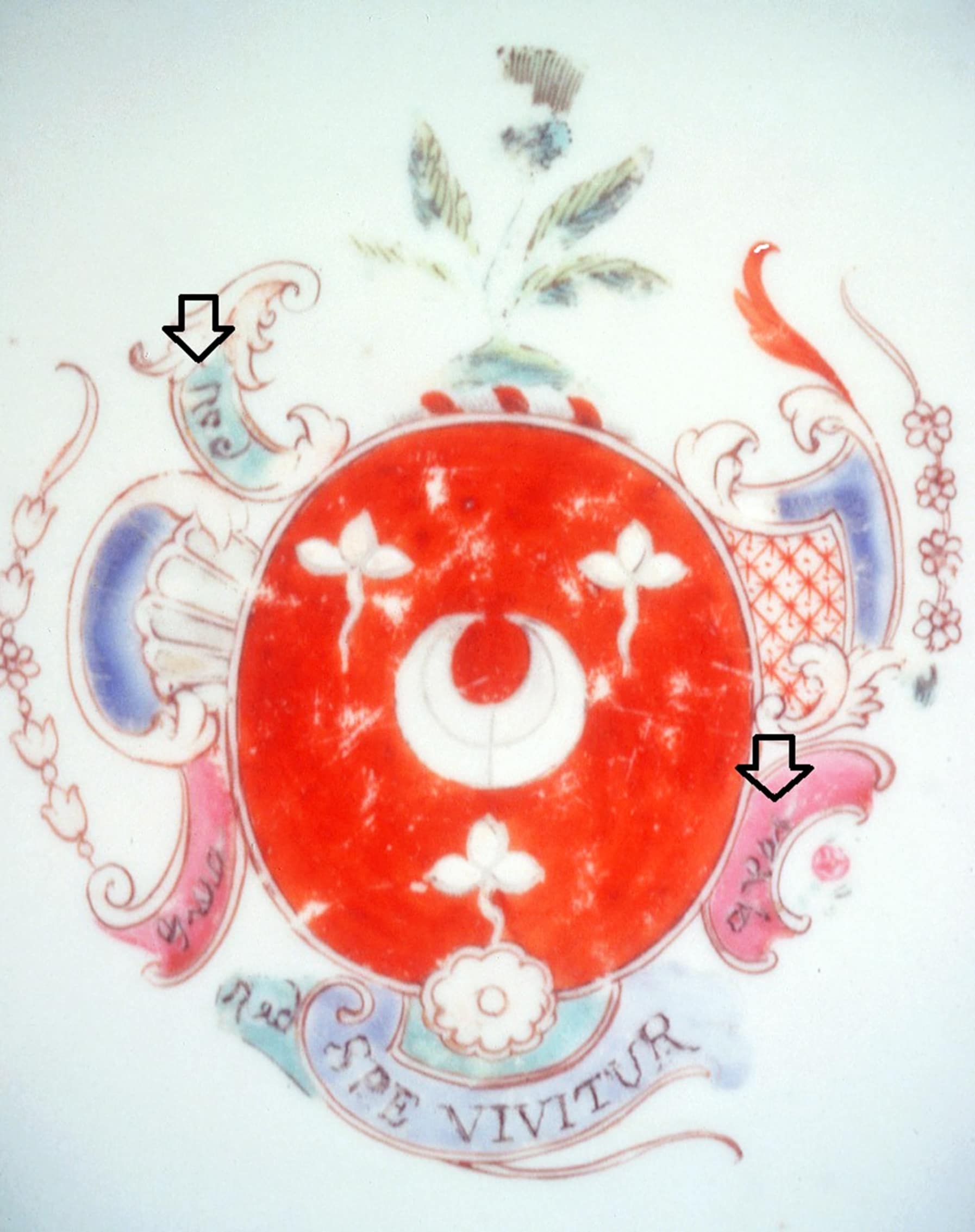

Creativity is often covert for collectors: It manifests as pattern recognition, emotional resonance with specific themes or periods, or even idiosyncratic taste. Why would a neurologist collect Chinese export porcelain? Because her brain’s networks are lighting up in ways that mirror classical creativity, even if she doesn’t think of herself as “creative” in the usual sense.

The Default Mode Network: Your Brain’s Inner Artist

We’ll start with the neural VIP: the default mode network (DMN). This constellation of brain regions—including the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), precuneus, and angular gyrus—is active when the brain is “at rest.” For example, it’s at work when you’re daydreaming, mentally time-traveling, or imagining new possibilities. This process pulls in autobiographical memories, social information, and symbolic meaning.

Researchers in this area found that the DMN is essential for divergent thinking, which involves generating multiple novel solutions. For collectors, this is the neural basis involved when they visualize how a new object fits into an existing collection or imagine its historical and emotional significance. It’s also why collectors often describe their acquisitions as meaningful: Their DMN connects dots across time, self, and symbol (Beaty, R.E. et al., 2018).

The Executive Control Network: Creativity’s Editor-in-Chief

Creativity is the executive control network (ECN) anchored in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) that exerts top-down control. It helps us assess whether an idea is sound, coherent, or realistic.

For collectors, the ECN is engaged during a collector’s curation of her objects. Should I bid on this 1740 famille rose plate? Do I already have something similar? Is it a fake? This evaluative process, crucial in seasoned collectors, requires the ECN to step in and apply logic to emotional impulses.

This honed creativity appears to require a balance between the DMN and ECN in creative people. Collectors can be expected to have a stronger functional connectivity between these networks, which allows them to oscillate between unrestrained imagination and careful judgment (Beaty, R.E. et al., 2016, 1).

The Salience Network: The Brain’s Bouncer

Although the precise function of the salience network remains under investigation, it is thought to play a key role in identifying and integrating emotionally and sensorily relevant stimuli (things that make something stand out to you from its surroundings). It also facilitates the dynamic shift between internally focused thought, governed by the default mode network, and externally focused cognitive tasks, managed by the central executive network – essentially serving as a gatekeeper between the two. Structurally, the network is primarily composed of the anterior insula and the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), regions believed to be critical in evaluating the significance of the incoming salient information.

For example, imagine walking through an antique store: 400 objects scream for your attention, but only one—the 18th-century Chinese export teapot—makes your heart race. That moment of “aha!” or gut-level attraction is governed by the salience network, which filters between spontaneous ideas and disciplined focus.

For collectors, this balancing act is crucial. The salience of a potential object (the emotional punch it delivers) must be compelling enough to override logic. (This is how you end up explaining to your partner that the two of you own 200 teapots and have nowhere to put them) (Ekhtiari, H. et al., 2016, 2).

Dopamine and the Creative Reward Circuit

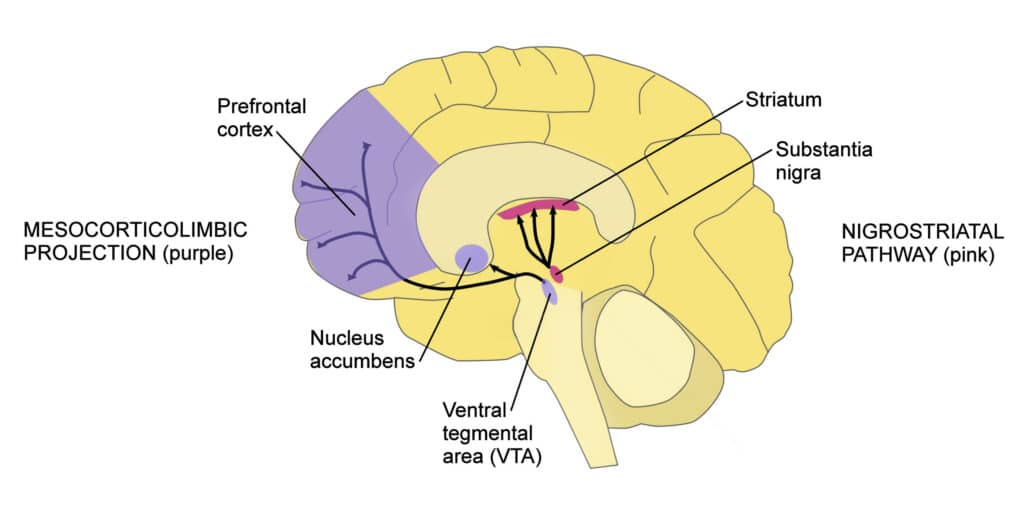

Creativity, like collecting, gives a dopaminergic rush. It is closely tied to the brain’s reward pathways, especially the mesolimbic system involving the ventral tegmental area (VTA; VTA neurons release dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and motivation, in response to rewarding stimuli) and nucleus accumbens (NAcc; a key part of the brain’s reward system). These structures release dopamine (known as the feel-good neurotransmitter) when encountering something novel, unexpected, or intrinsically rewarding.

When collectors describe “falling in love” with an object, they often are experiencing a dopaminergic burst. This reward response isn’t random but honed by years of aesthetic, historical, or emotional cues. Creativity researchers call this a “predictive reward signal”: Your brain rewards you for novelty, especially novelty that matches your taste. Dopamine also facilitates exploratory behavior, encouraging a collector to try something new, such as expanding a collection in new directions (Salimpoor, V.N., 2011).

Summary: Collecting as Neural Improvisation

Creativity isn’t a bolt of celestial lightning. It’s a series of neural negotiations among brain networks that imagine, evaluate, filter, and reward. This interplay is often instinctive for collectors: You don’t “decide” to be moved by an object. Instead, your brain creates that sensation by harmonizing internal memory, aesthetic expectation, emotional salience, and reward anticipation.

References

Beaty RE, et al. 2018. “Robust prediction of individual creative ability from brain functional connectivity.” PNAS.;115(5):1087–1092.

Beaty RE, Benedek M, Silvia PJ, Schacter DL. 2016 Creative Cognition and Brain Network Dynamics. Trends Cogn Sci. Feb;20(2):87-95. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.10.004. Epub 2015 Nov 6. PMID: 26553223; PMCID: PMC4724474.

Ekhtiari, H., Nasseri, P., Yavari, F., Mokri, A., & Monterosso, J. (2016). Neuroscience of drug craving for addiction medicine: From circuits to therapies. In H. Ekhtiari & M. Paulus (Eds.), Progress in Brain Research (Vol. 223, pp. 115–141). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2015.10.002(PMC)

Shirley M. Mueller, M.D., is known for her expertise in Chinese export porcelain and neuroscience. Her unique knowledge in these two areas motivated her to explore the neuropsychological aspects of collecting, both to help herself and others as well. This guided her to write her landmark book, Inside the Head of a Collector: Neuropsychological Forces at Play. In it, she uses the new field of neuropsychology to explain the often-enigmatic behavior of collectors. Shirley is also a well-known speaker. She has shared her insights in London, Paris, Shanghai, and other major cities worldwide as well as across the United States. In these lectures, she blends art and science to unravel the mysteries of the collector’s mind.