The Business of Selling in Group Shops – Business of Doing Business – The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles –

By Ed Welch

The group shop is a popular method of selling antiques. As with all other methods of selling antiques, the group shop has its advantages and its disadvantages. By understanding the strong and weak points of group shop selling, a dealer is more likely to make a profitable return on investments.

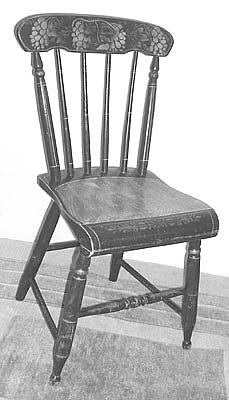

Last year I bought a set of six signed Walter Corey chairs from a group shop in southern Maine for $340. I sold the set at an antiques show for $1,850. The dealers who had previously owned the chairs were at the show. They were flabbergasted that I sold the chairs for such a high profit because they used a price guide that said the value was $65 to $85 per chair. The only other information they had about the chairs was “Walter Corey 52 & 54 Exchange St. Portland, Maine” stamped on the bottom of each chair. This was their first mistake.

Here is what I know about Walter Corey: Corey moved to Portland Maine in 1836. He bought a furniture manufacturing business on Exchange Street. A one-horse-powered treadmill operated the factory. Corey hired Jonathan O. Bancroft, a local engineer and furniture maker, to design equipment to mass-produce chair parts. Together, these two men revolutionized the process of making furniture.

At that time all chairs were handmade and sold for $20 or more each. Corey envisioned that he could substantially reduce the price of a chair by using interchangeable mass-produced parts. By doing so, he could sell more chairs. Jonathan Bancroft was so successful in designing chair-making machines that the Corey Company was able to lower its price per chair to just 37 cents in five years. The Corey Company had to build a second manufacturing plant in Westbrook to keep up with demands. They also replaced the horse powered treadmill with a steam engine. Corey chairs were shipped all over the world. As a result, Walter Corey is recognized as a pioneer in the development of machine made furniture. The manufacturing techniques he caused to be invented lowered the cost of furniture making. Furniture such as chairs, tables, chests, stands, and beds became affordable to middle and working class families.

Finally, each chair was stamped JOB followed by the number 17 handwritten in ink. I believe that this stands for Jonathan O. Bancroft and that this was the 17th set of chairs made. He could not have continued this hand stamping for long because the company was soon turning out tens of thousands of chairs yearly.

Although the chairs’ previous owner did not know this, information on Walter Corey is readily available. The Magazine Antiques featured Corey Chairs in their May 1982 issue. The Maine State Museum held a yearlong exhibition on Walter Corey and his furniture. The museum also owns a rare signed set of chairs made by Bancroft.

Finally, Earl G. Shettleworth Jr., director of the Maine State Historic Preservation Commission, and William D. Barry, of the Maine Historical Society, have written extensively about Walter Corey and his furniture manufactory.

The previous owners made several common mistakes: they relied on a price guide; they failed to do any research on the subject; and they offered a high-level antique for sale in a low-level group shop. Not that groups shops were the problem, specifically. These chairs could have sold for $1,850 if they had been offered in a high-level group shop. In addition, photocopies of The Magazine Antiques article, the Maine State Museum catalog, and the article by Shettleworth and Barry should have been made available to the buyer. Providing documentation is a good selling technique and a responsibility of the seller.

The antiques trade is divided into ten levels based on selling price. Successful dealers know the level at which they deal. They buy and sell only those items that are priced within that level.

Group shops are one of the best things that ever happened to the antiques trade. They have freed dealers from the time-consuming drudgery of selling. Group shop rents are cheap – too cheap, in my opinion. Low rent has prevented the full growth and development of the group shop method of selling.

For example, trade papers serve the entire ten levels of the antiques marketplace. Auction services serve the entire ten levels. Antiques shows serve the entire ten levels. Group shops, with a few exceptions, serve only the low and middle range of the antiques trade. Generally, group shop rental income is too low to support the expense of marketing high-level antiques. Group shop selling is the least personal method of selling. No interaction takes place between the buyer and the seller. This is a disadvantage to the seller, generally resulting in lower profits on each item sold.

The primary motivating factor in all group shop sales is price. If an item is perceived to be priced cheaply enough, it will sell. This is not necessarily the case in sales that take place in individually owned shops and at antiques shows. In personal, one-on-one, selling, the knowledge and enthusiasm of the seller plays an equally as important part in generating the sale as does the price.

An aggressive dealer of middle- to high-end antiques can he expense of marketing (selling) his or her merchandise. Personal advertising puts the owner back into the selling process of sales made in the group shop setting. Your ads reflect your personality, your knowledge, and your individualism. When a buyer travels miles to visit your booth at a group shop, that buyer is less focused on price.

In addition, if the other items in your booth are of quality and displayed tastefully, the buyer’s focus on price is further reduced. It also helps if the antiques on display in adjacent booth are also of a high quality and attractively arranged. You can further personalize group shop selling by leaving business cards in your booth. This allows interested buyers to speak with you personally. You should also leave reference and research materials on each item offered for sale.

Finally, offer a 15 percent discount (the standard discount is usually ten percent) on any item purchased as a result of an ad. Require that the buyer sign the ad and ask the buyer for his or her mailing address. Most group shop owners will do this extra work for you because your ads are bringing extra customers into their shop.

Send a personal hand-written thank you card to everyone who buys from you, regardless of the amount of the sale. I realize that sending thank you cards takes a lot of time. I just returned from a show at which I made nearly 50 sales, and I will spend several hours writing thank you notes. The pay-off is that nine repeat customers spent $5,176. A thank you card is as good as future cash.

I still do business with customers I gained while selling through group shops in the 1970s. From a business point of view, it makes little sense to sell a fine antique without attempting to establish a business relationship with the buyer. That buyer is the most likely person to buy a similar item in the future.

Rent space in a well-managed group shop. Budget two to three times the rental cost for advertising. Generally, the total amount will be less than the cost of one high-level show and much less than the cost of running your own shop.

The secret of making money selling from group shops is to take as much control of the selling process as possible. Do not confuse writing the sales slip and taking payment with selling. Attracting your own buyers through advertising is the best way to accomplish this goal. The only other option is to sell so cheap that price alone makes the sale.

-

- Assign a menu in Theme Options > Menus WooCommerce not Found

Related posts: