by Kary Pardy

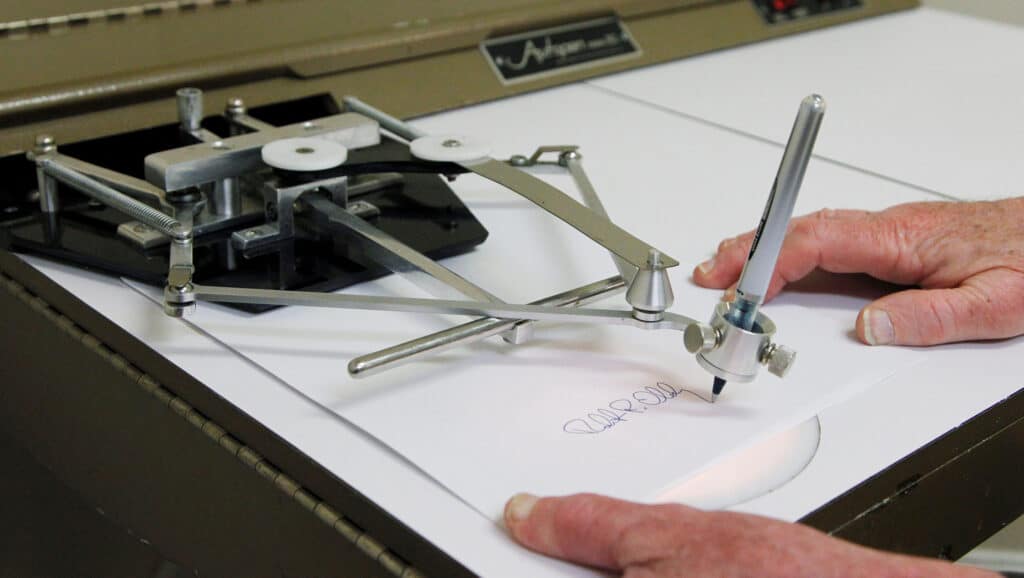

Footage from a 1950s 9-second video shows a grey, boxy machine using mechanical levers to exactly mimic the slopes and angles of a person’s handwriting. Since the invention and popularized use of the power autopen in the mid-1900s, it’s been making the lives of celebrities and politicians easier while at the same time frustrating autograph collectors everywhere. While autopen signatures and written documents can be tricky, they are not impossible to spot, particularly when you’re equipped with the right information. Knowing the autopen’s origins and methods will help collectors spot such signatures out in the wild, and the more you know, the closer you’ll be to deciding whether you want to collect or avoid this notorious handwriting mimic.

From The Beginning

To begin, the term “autopen” has become the generic catch-all for machines that duplicate human handwriting, and most specifically, signatures. The earliest example dates back to an 1803 patent filed by inventor John Isaac Hawkins, who also is credited with designing the first upright piano and an early mechanical pencil. Thomas Jefferson took an interest in Hawkins’ invention, known as the polygraph, and is purported to have used it frequently.

The public wouldn’t gain access to mechanical writing until 1937 with the invention of the “Robot Pen” or using Robert M. De Shazo, Jr.’s more successful option introduced in 1942. De Shazo’s autopen gained traction with the American government – Gerald Ford and Harry Truman are both rumored to have been users. Lyndon Johnson was the first president who allowed his autopen usage to be documented in a 1968 National Enquirer story entitled, “The Robot That Sits In For The President.”

The “Autopen” name itself comes from the International Autopen Company of Arlington, which manufactured machines by that name. Their Model 50 was heavily used by John F. Kennedy’s team to sign his name. The use of autopen devices was so prolific within the US government that in 2005, the Justice Department made it official and issued a ruling that upheld the right of Presidents to sign bills with autopen devices.

Beyond “Official Duty”

Of course, government officials were not the only ones to benefit from the autopen’s services. Celebrities, sports stars, executives, and anyone who needed easy writing duplication found help with an autopen. While earlier models used a sample piece of handwriting and a carved matrix for the pen to follow, more recent examples use stored digital images or magnetic media. The real trick with autopens is that most were equipped with an “arm” that could hold almost any pen or writing device. Therefore, the ink or any smudges won’t give this type of signature away – for that, you have to look deeper and consider the very nature of the autopen.

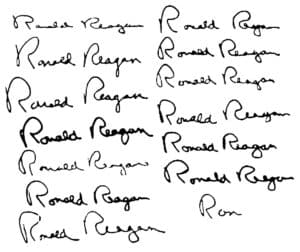

These machines were created to duplicate signatures, handwriting, and even entire letters in large quantities, and each copy will be exactly the same.

Verify That Signature

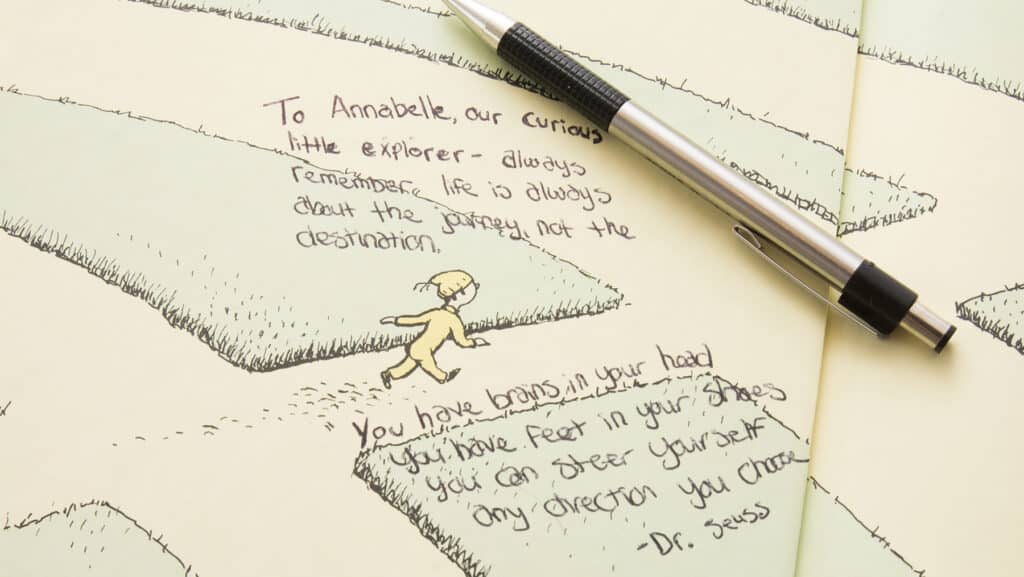

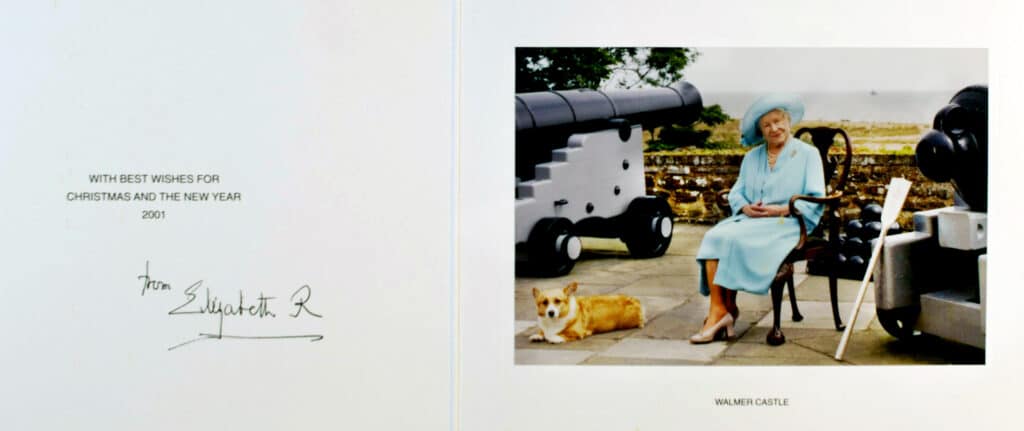

If possible, a buyer should compare documented, genuine writing samples from the signer in question, and research to see if they were a known autopen user. Several presidents have their autopen signatures on file, and you can use those as a reference. You can even go so far as to place your signature on top of a known autopen signature and see if they line up. The genuine article shouldn’t be an exact match – when was the last time you signed something in exactly the same place, with the same size letters that were all identically formed, with no flourish out of place? Humans typically don’t write with that kind of mechanical precision.

Unfortunately for collectors, many famous people made multiple autopen signatures for an added air of authenticity. Richard Nixon had around twenty-five signatures, while John F. Kennedy had eight. Hope is not lost, however. Collectors should break out their magnifying glasses and take a closer look at the signature in question. Autopens by nature are consistent, while a human hand lifts and presses when writing. Inspect for any changes in pressure or any differences in the ink thickness. Autopens keep a constant pressure when signing and thus will produce lines of exactly the same width throughout the signature. They also produce a “drawn” appearance that does not flow as cleanly as a real signature might. They start from a static position and finish with a stop, meaning that there might be slight ink pooling at the beginning and end of the signature, whereas when humans are signing, they don’t linger around when the signature is done. Lastly, older autopen models might jam slightly at times, causing a quick shake of the pen.

Admittedly, these telltale signs are minute, and if you are ever in doubt, do not hesitate to contact an expert. Beyond just years of experience with handwriting, experts often have access to a library of reference signatures which could greatly aid in solving autopen mysteries. You can also reference the May/June 2020 issue of Journal of Antiques and Collectibles article on forged signatures (on page 24) for further identification tips. (click on the link here for the online article.)

Value of an Autopen Signature

Autopen signatures are the bane of autograph collectors, and they do command much lower prices than their personally signed counterparts, but as time puts distance between collectors and autopen signers, they are not without value entirely. Collections of autopen signatures or celebrity ephemera sell well at auction, and some desirable lithographs with autopen signatures are popular with collectors. Examples include Apollo 11 crew lithographs from 1969 that bring a few hundred dollars at auction with autopen signatures or limited release presidential

invitations that are mechanically signed.

Interested more in the technology? Modern autopen machines are anywhere from $5,000 to $10,000, while vintage examples hover around $1,000 and rarely appear on the market. Whether you chose to embrace autopens or avoid them, a better understanding of the technology is the first step.

Related posts: