While the use of glass in the making of everything from jewelry to stained glass windows, optical lenses, architectural structures, decorative objects, and home furnishings is commonplace today, so is its use as a common metaphor: a “heart made of glass,” “glass houses,” “shattered glass” and “glass ceiling” all speak to both the strength and fragility of glass.

Glass Ceiling is used as a metaphor to refer to the invisible barrier that prevents someone from a given demographic from rising above social norms and other obstacles when seeking career advancement. Although initially applied to women in the workplace, today the metaphor has expanded to include anyone of any gender, color, or racial background. When they are the first from their group, they “shatter” the glass ceiling, leaving a clear path for others from their marginalized community to follow.

In this issue, we explore the “Glass Ceiling” metaphor as it relates to women and the role they played during the Golden Age at Tiffany Studios. Here is a story that might never have been told had it not been for one woman—Tiffany Lead Designer Clara Driscoll—who wrote hundreds of letters to her mother and sisters back home in Ohio during her tenure at Tiffany Studios in New York City from 1888 to 1909. Driscoll’s letters, only discovered in the past two decades, provide glass historians and scholars a rare first-person account of the activities at Tiffany Studios at that time, as the company’s corporate records did not survive. They also shine a light on Driscoll’s cohort, known as the “Tiffany Girls,” and their contributions to designing and working on some of Tiffany’s most iconic pieces.

In some ways, Louis Comfort Tiffany would be considered progressive for his time when it came to hiring women. He was known to employ dozens of women workers in his glassworks in the last decades of the 19th century and even placed some such as Clara Driscoll, Agnes Northrop, and Julia Munson in managerial and lead designer positions. He also recognized and capitalized on the unique skill set and aesthetic women artisans brought to their work. And, he was known to compensate his Tiffany Girls equal to their male counterparts. On the other hand, women still needed to know their place in Mr. Tiffany’s world. Once a woman in his employ married they needed to leave the company, no matter who they were or the work they performed. And, as he considered his name to be a brand, he rarely spoke publicly of his designers or gave them the credit they deserved. That has come posthumously thanks to the Clara Driscoll letters which re-connect some of Tiffany’s most iconic designs with their makers and share the story of women in the workplace at that time. You can read more about the Tiffany Girls and their contributions to Tiffany Studios in my article “Glass Ceiling” on page 32 in this month’s “Made of Glass” issue.

While Driscoll and the other Tiffany Girls may have broken the proverbial glass ceiling, it shattered quietly. It wasn’t until the United States Commission of Labor issued its Annual Report in 1902 that women in the field of glassmaking got their public due: “Some manufacturers do not want female designers … Once employed, they are preferred, because they are naturally of a more artistic temperament. They display more taste, are always reliable, and can do fully as good work as men. lt is the opinion that the competition and employment of women in the field of design … has tended to improve the work of men.”

This report only reinforced what many glass insiders such as Louis Comfort Tiffany already knew: women had an important and equal part to play when it came to glassmaking. It also made glassmaking a craft for suitable employment among a new generation of 20th-century women designers and artisans; however, their right to work did not necessarily extend to receiving credit for their contributions. That would take a few more decades.

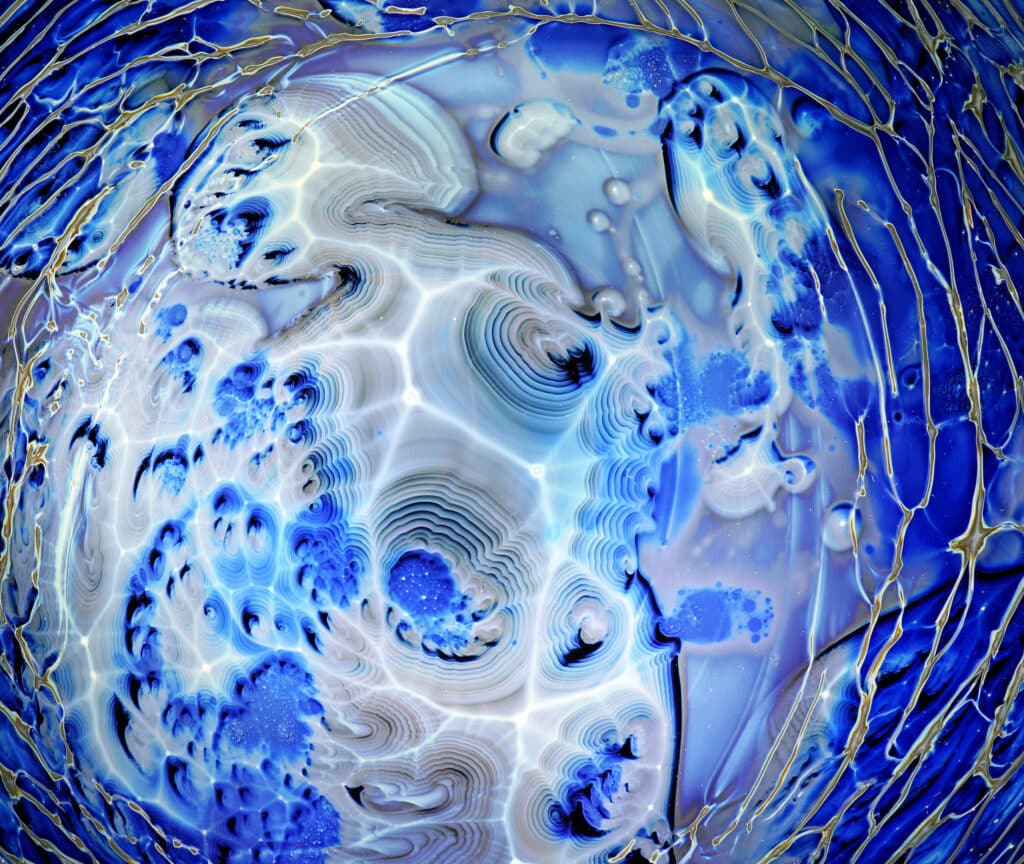

As we think about the glass that people collect when we pull together our editorial features for this annual glass issue, we also keep our eye on emerging collectibles and glassmakers in the contemporary art glass world. Here, Managing Editor Judy Gonyeau had a unique opportunity to visit with Josh Simpson, a contemporary American artist who just celebrated 50 years of producing glass objects at his studio in Shelbourne Falls, MA. Simpson creates one-of-a-kind, space-inspired glass art held in the collections of museums such as the Corning Museum of Glass; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the Renwick Gallery. His universe of glass art is coveted and collected and his vision for glass is worth sharing, as Judy does in her article on page 36.

Also in this issue, we share an article with information from the Corning Museum of Glass along with Peach Ridge Glass on the history and use of glass canes, and Peter Wade helps us navigate the internet to learn more about and identify our glass. As always, thank you to the many glass clubs, collectors, museums, and auction houses that continue to participate in this, our 16th annual glass issue. We continue to be inspired by the history and stories you share with us. After 16 years, we still think there is more to tell.

If you have an interest in glass and want to connect with fellow enthusiasts, zoom in on a lecture, see a museum exhibition, or attend a show or convention, consult our Resource Directory of Glass Clubs and Museums on page 45, and special News & Notes throughout the glass section starting on page 25. Want more glass? You can also read features from the past 16 years of glass issues by visiting the Editorial Archives page of our website at www.journalofantiques.com and searching “Glass” under “All” categories. Like glass itself, our editorial covers glass from the hundreds of different angles that make it so alluring.

Related posts: