By Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

Despite the constraints of slavery, poverty, lack of education, and social and racial discrimination, these seven men defied the odds and went on to influence, through their inventions, transportation in America in small but significant ways:

Benjamin Montgomery (1819-1877)

Born a slave in Loudoun County, VA, and later sold to Joseph Davis, brother of Jefferson Davis, future president of the Confederacy, Benjamin Montgomery’s aptitude as a mechanic did not go unnoticed on the plantation, where he was encouraged to better himself and his education. He learned to survey land and used this skill to plan the construction and maintenance of various levees for flood protection. He even learned to draw architectural plans and assisted in the construction of many large buildings on the plantation, including an elaborate garden cottage. He was so talented and versatile that at one time he managed both Davis brothers’ plantations.

During the late 1850s, Benjamin invented a steamboat propeller designed for shallow waters, such as the water near the plantation on which he lived. At that time, commerce often flowed through the rivers connecting counties and states. With differences in the depths of water in different spots throughout the river, navigation could become difficult. If a steamboat were to run adrift, the merchandise it carried could be delayed for days, if not weeks.

The blades Montgomery invented were designed to enter the water at an angle, making a much more efficient use of power than other propellers. In 1858, he filed for but was denied a patent on the basis that he was a slave and as such, not considered a citizen, a requirement at the time for receiving a patent.

Benjamin Montgomery went on to become one of the wealthiest cotton planters in post–Civil War Mississippi. He owned thousands of acres of land and founded and ran a market center called Montgomery and Sons that included a store, several warehouses, and a steam-driven cotton gin and press.

Matthew A. Cherry (1834-?)

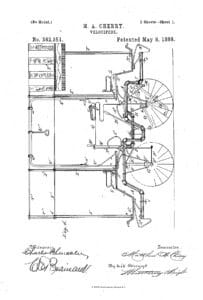

Matthew Cherry may have faded from public records, but his impact on transportation endures. Cherry’s journey into the world of invention began with the development of the velocipede, a precursor to the modern-day bicycle. This early device featured a metal frame with two or three wheels and allowed riders to propel themselves forward by moving their feet along the ground, akin to a fast walking or running motion.

Cherry’s inventive spirit led him to improve upon existing designs, culminating in a patent granted on May 8, 1888, for the tricycle. Even today, tricycles are the choice of transportation for many as opposed to bicycles, because of their increased safety and carrying capacity. Additionally, the tricycle has increased stability from the third wheel, which can make it easier to carry objects from place to place.

Seven years later, and unrelated, Cherry set out to solve a problem with streetcars. Whenever the front of a streetcar accidentally collided with another object, the streetcar was severely damaged, often having to be completely replaced. Cherry patented the streetcar fender on January 1, 1895, adding a layer of safety for passengers and employees. The fender, which was a piece of metal attached to the front of the streetcar, acted as a shock absorber, thereby diminishing the force of the impact in the event of an accident. This device has been modified through the years and is now used on most transportation devices and is known as the “bumper.”

Benjamin (Boardley) Bradley (1830-1904)

Benjamin Boardley was born a slave in Anne Arundel County, Maryland in 1830. It has been theorized that he acquired literacy while learning from his master’s children.

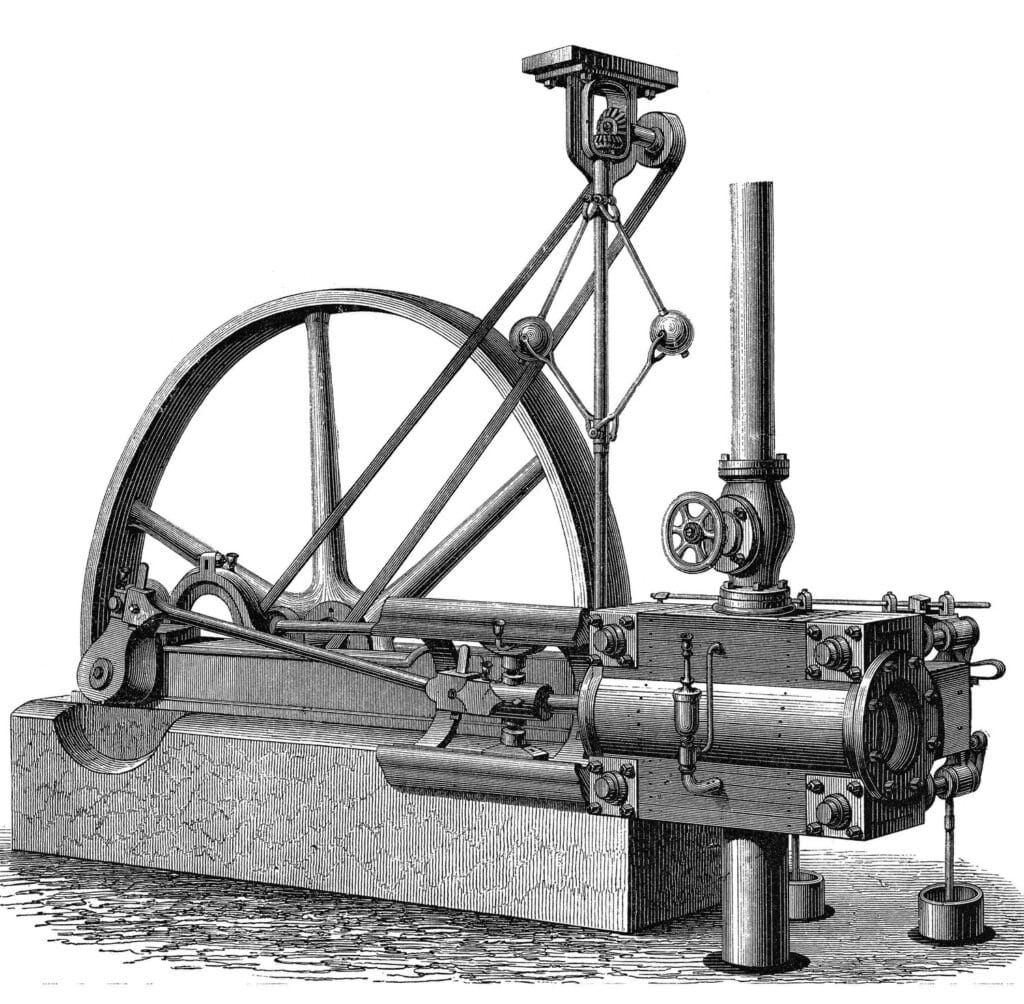

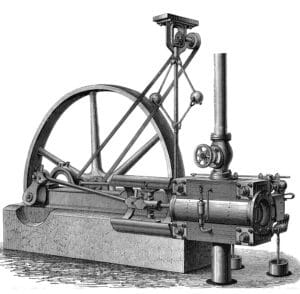

Bradley, as he is sometimes called, showed ingenuity and mechanical skills by the age of 16, when he built a steam engine out of a gun barrel, pewter, round steel, and other various materials. His master was impressed and was able to get him a job as a helper in the Department of Natural and Experimental Philosophy at the Naval Academy at Annapolis. As a helper at the academy, Bradley helped set up science experiments that involved chemical gases.

During his time at the Naval Academy, Bradley built a steam engine and sold it to a Midshipman. With the money he made from selling the steam engine and the money that he had saved while working at the Naval Academy, he developed and built a steam engine in 1859 large enough to run “the first cutter of a sloop-of-war” at a speed of 16 knots (18 mph). In 1859, an article about his invention appeared in the African Repository, wrongly spelling his surname as Bradley, which has been attached to him throughout history.

Bradley was unable to patent his invention under United States law because he was a slave. He was, however, able to sell the engine and use the proceeds—plus the money given to him by professors at the Naval Academy—to buy his freedom for $1,000 (roughly $34,000 in 2023). He went on to become an instructor in the Philosophical Department at the Naval Academy in 1864 and continued his work constructing small steam engines and applying his ingenious mechanical skills.

Elijah McCoy (1844-1929)

Elijah McCoy was born in 1844 in Colchester, Ontario, to George and Mildred Goins McCoy. At the time, they were fugitive slaves who had escaped from Kentucky to Ontario thanks to helpers from the Underground Railroad.

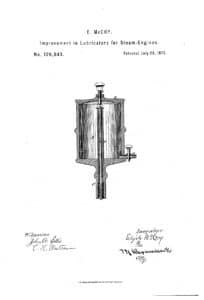

Educated in black schools, McCoy was sent to Scotland in 1859 at the age of 15. While there he was apprenticed and, after studying at the University of Edinburgh, was certified as a mechanical engineer. Despite his qualifications, McCoy was unable to find work as an engineer when he returned to the United States in 1859/60. Due to racial barriers, skilled professional positions were not available for African Americans at the time, regardless of their training or background. Instead, he found work as a fireman and oiler at the Michigan Central Railroad. While in this line of work, McCoy developed his first major invention after recognizing the inefficiencies inherent in the existing system of oiling train axles.

Working out of a home-based machine shop he set up, McCoy invented an automatic lubricator for oiling the steam engines of locomotives and ships, patenting it in 1872 as “Improvement in Lubricators for Steam-Engines” (U.S. patent 129,843). McCoy’s invention allowed railroad steam engines to be lubricated without stopping the train, saving time and money. It is alleged that the quality of his devices became so well-known that people buying a piece of machinery would make sure it came with his lubricating system by asking for “the real McCoy.”

McCoy continued to refine his devices, receiving nearly 60 patents over the course of his life. While the majority of his inventions were related to lubrication systems, he also developed designs for an ironing board, a lawn sprinkler, and other machines.

Andrew Jackson Beard (1849-1921)

Born in about 1849, Andrew Jackson Beard spent the first fifteen years of his life as a slave on a small farm in Eastlake, Alabama. Despite having no formal training, Beard went on to become an accomplished inventor.

In 1872, after working in a flour mill in Hardwicks, Alabama, Beard built his own flour mill, which he operated successfully for many years. This led him to invent and patent a new double plow design in 1881 that adjusted the distance between the plow plates. Beard later sold his invention for $4,000 (equivalent to $140,000 in 2023).

After the sale of his first patent, Beard returned to farming. In 1887, he patented a second double plow design that allowed for pitch adjustment, which he sold for $5,200 (equivalent to $180,000 in 2023). He invested his earnings into real estate and began to work with and study engines.

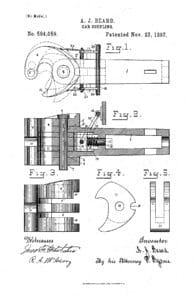

In 1882, Beard received a design patent for a new rotary steam engine and took out two patents in 1890 and 1892 to improve the Janney coupler, a device used to link train cars and locomotives together. Before Beard’s patent, the coupler required railroad workers to complete the dangerous task of manually placing a pin in a link between the two cars – a worker had to brace himself between the two cars and then drop a pin at exactly the right moment. Beard knew first-hand the dangers of this task as he had lost a leg in a car coupling accident.

Beard’s invention “coupled” the cars together automatically without the need for a worker to do so, no doubt saving countless lives and limbs. In 1893, the US Congress passed the Federal Safety Appliance Act, which made it illegal to operate any railroad car without automatic couplers, creating Beard’s lasting legacy to transportation safety.

Granville T. Woods (1856-1910)

Part Native American and part African American, Granville Tailer Woods, known as the “Black Edison,” grew up in poverty in Columbus, Ohio, leaving school at age 10 to apprentice in a machine shop where he learned the trades of machinist and blacksmith.

At age 14, Woods obtained a job as a fireman on the Danville and Southern Railroad in Missouri, eventually becoming an engineer, and in 1880, the chief engineer of the steamer Ironsides.

In 1880, Woods moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, and established his business as an electrical engineer and an inventor, receiving his first patent in 1884 for a steam boiler furnace. In 1885, Woods patented an apparatus that was a combination of a telephone and a telegraph. The device, which he called “telegraphony,” would allow a telegraph station to send voice and telegraph messages through Morse code over a single wire. He sold the rights to this device to the American Bell Telephone Company.

In 1887, Woods patented the Synchronous Multiplex Railway Telegraph, which allowed communications between train stations from moving trains by creating a magnetic field around a coiled wire under the train. This allowed trains to communicate with one another and prevented them from colliding into each other.

Throughout his lifetime, Granville Woods obtained more than 50 patents for inventions including an automatic brake, an egg incubator, a system for controlling electrical lights in theaters known as the “safety dimmer,” and for improvements to other technologies such as the safety circuit, telegraph, telephone, and phonograph.

Phillip B. Downing (1857-1934)

Born in 1857 in Providence, RI, Downing was the son of a successful businessman and abolitionist (cited in Downing’s obituary as “one of the best-known colored men of his day”) with an inventive mind.

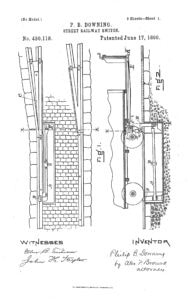

The first of Downing’s inventions, the “New and Useful Improvements in Street Railway Switches,” was approved for a patent in June 1890. It improved streetcar and train switches by allowing the switch to be opened or closed by the brakeman using a brass arm next to the brake handle on the platform of the car.

Downing’s long career in Boston as a postal clerk in the Boston Custom House brought about his next invention: the “street letter mailbox.” Before 1891, folks who wanted to send a letter would have to visit their local post office to do so. Downing’s invention of a metal box on four legs with a hinged opening to prevent rain or snow from entering the box and damaging the mail allowed for drop off near one’s home and easy pickup by a letter carrier. Today, we know his invention as the mailbox.

In total, Downing filed for at least five patents, including a handheld envelope moistener that utilized a roller and a small, attached water tank to quickly moisten envelopes and an easily accessible desktop notepad.