By Judy Gonyeau, managing editor

What do you think of when you see a harmonica? A blues player with hands wrapped around this small instrument while blowing a lot of air and generating a rusty, gutsy sound. A cowboy playing a quiet tune while sitting around the fire after a long day of ranching. An image of a Chinese person from 2500 B.C. playing a sheng.

Wait – What?

Origins of the Harmonica

One of the oldest Chinese “free reed” instruments is called the “sheng.” It consists of 17-21 reed pipes of varying lengths forming an incomplete circle around a “windchest” or chamber of either carved wood or metal. Its shape is said to have been inspired by the phoenix at rest on its nest.

Once you hear the sheng you will also hear many other instruments, including the harmonica, a pipe organ, and perhaps, as one player on YouTube played, the digital-sounding theme to Mario Brothers (Just Click Here).

So how did this “mini pipe organ” become the “mouth organ” we know today as the harmonica? Both are free reed instruments, which does not mean it is free of reeds, but that reeds are fixed at one end and set over an opening or slot that is barely wider than the reed itself. Sound is created when applying different pressures of air through the slot to make the reed vibrate in its place and therefore create the sound. For some instruments, this only occurs when blowing into it (“blow notes”), but for the sheng and the harmonica, sound also happens when inhaling through the holes on the instrument (“draw notes”).

Over the course of 45+ centuries, the playing of free reed wind instruments in different shapes and forms spread throughout South East Asia to the Philippines and Thailand, and then later to Korea and Japan. It was not until the 18th century that free reed instruments finally arrived in Europe thanks to the explorers and travelers who brought them back from their adventures.

Fast Forward to the 1820s

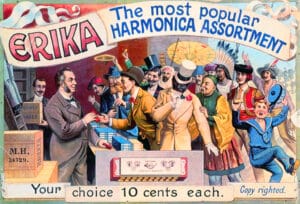

Once Asian free reed instruments arrived in Europe and were heard by a broader audience, manufacturers of similar devices were booming thanks to the First Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) as they began to tinker with the instrument and its sound so they could make their own versions.

In 1822 Berlin, Germany, 16-year-old Christian Friedrich Ludwig Bucschmann created an experimental version of the sheng that had 15 reeds which were lined up and of the same length reminiscent of today’s harmonica, and named it the “aura.” This was meant to be used as a pitch pipe for choruses and orchestras, but the simplicity of it made it quite the curiosity for a local clockmaker named Christian Messner.

Messner was on the lookout for another skill and product to boost his current clock repair business during the depression taking place at that time. He started manufacturing an inexpensive replica of the aura to sell at carnivals and local fairs as something anyone could play by blowing out into the mouthpiece across the different reed chambers. Messner kept his manufacturing methods secret – only members of his immediate family knew the construction specification for the Messner aura. The aura was a huge success and had a good profit margin. Soon enough other German craftsmen were making their own versions of the aura.

Who was Richter and Why is He Important?

Chronologically, the early to mid-1800s is a section where research regarding innovations made to the harmonica gets a bit blurry, and the “Richter” name pops up all over the place as a major innovator—or not—of the instrument.

– In some references, a gentleman named Joseph Richter is credited with developing the first diatonic harmonica that created sound through blow notes and draw notes in 1825.

– In other references, Richter’s name is highly questioned and the date of the breathing breakthrough is listed as anywhere from 1825 to 1879.

– The name “aura” was altered to “aeolian” or “aeolina” in many records, connected to a Richter.

– Just to add to the confusion, a Nuremberg merchant’s 1834 catalog shows a 10-hole harmonica with an ivory mouthpiece with no attribution but plenty of rumors as to who (Richter?) created it.

– Then there are multiple examples of Richter harmonicas with many different Richters named as makers who were spread across Germany – Anton Richter, Johann Richter from Regensburg, another from Bohemia, M. Johs. Richter in Saxony and the list goes on.

– The other innovation that made harmonica’s musical range ever greater, and may have been created by a Richter, is the double holed harmonica, where two notes could be played in the space that used to house only one, increasing the popularity of the instrument due to its ability to play more melodies.

Whether the Richter surname is connected to these improvements made to the harmonica is uncertain, but the changes made happened in rapid succession and made it more popular than ever.

Weiss Hohner Harmonicas

Harmonica manufacturing caught the attention of yet another (albeit former) clockmaker and successful businessman, 21-year-old Matthias Hohner. Apparently, Hohner payed a visit to his schoolmate Christian Weiss – a family member of Messner who took the maker’s construction methods and promptly opened his own company in 1856.

Hohner was looking for a new career and appeared to have overextended his visit, spending too many hours touring the Weiss factory. Becoming suspicious, Weiss threw young Hohner out. Hohner had seen just enough, however, and opened his own factory just one year later, 1857.

Hohner’s name became synonymous with the harmonica, but his musical attributes were few at best as he could barely play the instrument. Fortunately, Hohner was right where he needed to be to take on mass production of the harmonica and introduce it to the world.

Hohner made his first harmonica in 1857 and very quickly became the leader in this field of manufacturing. Within his first two decades in operation, he bought out the competition including Messner’s company, and began exporting his harmonicas to family in the U.S. By the time his four sons took over the business following Hohner’s death in 1904, the company was producing over 4 million harmonicas a year and employed over 1,000 workers.

Just five years after establishing the business, Hohner was exporting samples, and then box loads, of harmonicas to friends and family in the U.S. Making this instrument available to a new and growing audience in the West expanded his business exponentially. Thanks to the ongoing upgrades to both the design and range of the harmonica meant it was better able to fit in with the many different genres of music being played across the pond.

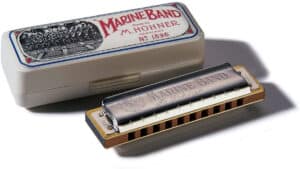

The Marine Band harmonica is perhaps one of the most iconic versions made by Hohner. Patented in 1896, it was named after the famous band led by American Composer and Bandmaster John Philip Sousa, but was really developed for European Folk Music. Due to its tonal possibilities, this harmonica became the go-to model for playing blues and country music.

Next up in 1910 came the ever-popular Chromatic harmonica by Hohner, allowing the player to perform music in any key. The Jazz age saw harmonicas joining the movement, and Blues performers were free to express themselves during the Great Depression and beyond.

Meantime, people participating in the western expansion had many, many hours in the saddle or riding the buckboard. The harmonica took on a more restful and range-y, even melancholy tone around the campfire. The harmonicas were cheap, small, and easily transported by the thousands of settlers who wanted and needed the music to create a sense of calm on the trail.

The 20th Century

The list of early players who made the harmonica a sensation included Little Walter, Deford Bailey (a regular at the Grand Ol’ Opry), and John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williams. Their recordings spread the news about the harmonica as a unique instrument with plenty of soul.

In the Big Band era, the Harmonicats entered the fray in 1947 as the only harmonica-led group ever known. That year they had a huge number one hit, “Peg O’ My Heart.” The group stayed popular right through the 1950s and had a Top 20 album in 1961. They tended to play popular standards and leaned toward sentimental songs. They continued to record music into the late 1960s hoping to stay current by recording popular songs such as “Get Off of My Cloud” by the Rolling Stones and “Blowin’ in the Wind” by Bob Dylan, and continued performing into the 1990s.

Another innovative player that took the harmonica to a new level was Howard Levy. In the 1970s, he discovered the “overblow” and “overdraw” technique that allowed him to hit all the notes of the scale in any key using the diatonic harmonica vs. a chromatic one. Like so many innovators of the instrument, he was young (only 19) and curious about this instrument.

Today, harmonicas are played by rock stars, country music performers, blues maestros, folk music geniuses, and everyone from Neil Young, Stevie Wonder, and The Brothers Gage to the kid next door. That is what made them become a part of the fabric of the U.S. and its diversity.

Related posts: