by Bill Thornbrook

It is a longstanding tradition for travelers from the Northeast to vacation in places with abundant sunshine, magnificent scenery and, let’s not forget, unique souvenirs to bring home. A prime destination for all these reasons has always been the great American Southwest. Among the most favored mementos of a trip to the Southwest are those that reflect the region’s special character. Silver and turquoise Native American jewelry, pottery, or rugs are popular reminders of travel to New Mexico or Arizona. Those who venture into Colorado have often selected an example of Van Briggle pottery.

Artus Van Briggle was an inspired potter and artist. Born in Ohio in 1869, he worked from an early age, beginning at Avon Pottery and then for twelve years at Rookwood in Cincinnati. His employer and Rookwood’s founder, Maria Longworth Nichols (by then Mrs. Storer), took note of the young man’s special talents and supported his study in Europe at her expense. There Artus observed and became smitten with aspects of the ceramic arts that were beyond his experience as an American potter. The blossoming Art Nouveau style excited him and he encountered ceramics with Orientalist motifs as well as the ancient Chinese matte glazes. He also fell in love with a fellow American art student living in Paris, Anne Gregory.

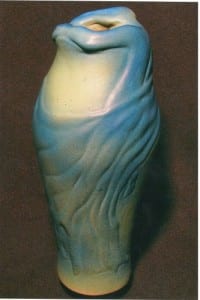

Van Briggle brought each of these discoveries into his art and his life. Returning to Rookwood in 1896 he dedicated himself to unlocking the secret of the dead matte glazes, which he planned to apply to the sensuous Art Nouveau-inspired vessels he was now creating. These efforts culminated in his ìLoreleiî vase (1898), inspired by a mythical Rhine River goddess and obligingly modeled for the potter by the attractive Miss Gregory, by then engaged to Artus.

Even as his career flourished, Artus himself was failing. He had contracted tuberculosis, and conditions at the Ohio pottery only contributed to his declining health. At age 30 he went west to seek a healthier climate. Gradually, after his arrival in Colorado Springs in March of 1899, Artus felt sufficiently improved to begin assessing the potential for creating art pottery in his new situation. He discovered local clay sources and concocted glaze formulas that he tested in the local college’s chemistry lab. Anne came the following year to assist Van Briggle in his efforts. The couple proclaimed their new partnership with the conjoined “AA” logo incised on the base of Van Briggle pottery ever since.

By the time they married in 1902, Artus’s art pottery was already achieving wide recognition. His hand-modeled exhibition pieces, finished with remarkable satin matte glazes in a palette of soft natural colors, continued to merit critical attention in European art circles and at home. The small kiln where his work progressed was proving inadequate, however. So with the support of his earlier employer, Mrs. Storer, and some of Van Briggleís progressive Colorado Springs neighbors, capital was raised to expand his studio and kiln. But Artus was by then too ill to make use of it and in July 1904 he died of tuberculosis.

Anne oversaw construction of a new Van Briggle Memorial Pottery at Glen Avenue and Uintah Street in 1907. On its completion she assumed additional roles in the operation. A talented artist in her own right, Anne was responsible for half of the nearly 900 pottery designs developed between 1900 and 1912. One of her former art students, Emma Kinkead, created many of the other designs during her time at the pottery.

The young widow remarried a few years after Artusís untimely death. Her new husband discouraged Anne’s involvement with the pottery after 1910. From that point, the Van Briggle firm produced little more in the way of art pottery, shifting instead to supplying ceramic tile to area homes and businesses for use in fireplace surrounds and flooring. Within a few years, the pottery had fallen on hard times and was sold in 1913. It would change hands several more times by 1920. That year, the Lewis brothers purchased the business and resumed making pottery.

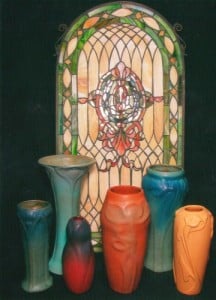

The Lewises were largely responsible for much of the Van Briggle pottery that collectors see today. Their production wares, slip-cast in molds often based on the earlier Van Briggle designs, were finished in lively matte glazes. The most popular finishes were Ming Turquoise, Mulberry/Persian Rose, and Mountain Craig Brown, though other glaze colors were periodically introduced and enjoyed limited popularity. The primary glaze was often oversprayed with a complementary secondary color accent.

The “new” Van Briggle pottery reflected the social and economic conditions of the times. The wares appealed to the middle class with their tasteful designs (often copied directly from Artus and Anne’s originals) in attractive colors at an affordable price for home decorating or gift-giving. Even so, the pottery’s hard times were not entirely left behind. A 1935 flood heavily damaged the Memorial Pottery building, along with most of the business records. Molds, pottery inventory, and even some of the glaze recipes were lost (including that for Mountain Craig Brown). In the 1950s, Van Briggle removed its operations to a former railroad roundhouse facility on South 21st Street.

Colorado Springs visitors have long enjoyed free guided tours of the Van Briggle studio. They viewed examples of Artus’ early art pottery, watched demonstrations at the potter’s wheel, saw the slip-casting process, finishing stations, and kilns, and then visited the showroom to consider a purchase. Countless thousands over the years accepted the standing invitation, resulting in Van Briggle pottery being filtered out across the nation.

Van Briggle’s appeal to collectors is understandable. Early originals by Artus are, obviously, much in demand and very pricey. But many of the later production pieces share comparable aesthetic traits in form and finish. Van Briggle pottery is both beautiful and functional, and an adequate supply feeds the collector market. Moreover, enthusiasts can readily refer to comprehensive guides to identify their pieces and establish relative values. Online auction sites, antique shops, and the occasional estate sale are reliable sources of Van Briggle pottery. A few years ago, a limited variety of fake Van Briggles appeared in the marketplace, but these pieces have been discredited and the practice seems to have ceased.

The most desirable items to look for are those that can be dated prior to Artus Van Briggle’s 1904 death, especially any attributable directly to his own hand. His early exhibition pieces are extremely rare but do exist. Also desirable are many of the forms originally designed by Artus or Anne and made prior to 1912, the year Anne withdrew altogether from the pottery.

Clues to dating Van Briggle pottery are covered in the collector guides and are fairly straightforward. Bases were routinely dated until 1907 and then again for a while after 1912. Even undated pieces may be approximated by reference to clay type, design, color, or other characteristics, including the excess glaze that typically produced a “dirty bottom” effect in the late teens. Relatively little pottery was produced between 1910 and 1920, so items from this era are less common. Pieces incised “U.S.A.” date specifically to the early1920s, when Van Briggle was exporting the wares to Australia.

While vases and bowls comprise the vast majority of Van Briggle’s output, collectors also pursue specialty items such as tiles, bookends, lamps, plaques, busts, mugs, and other novelties. Pieces incised “original” on their bases generally represent one-of-a kind items that were hand-thrown by a Van Briggle potter during demonstrations for

visitors taking the studio tour.

-

- Assign a menu in Theme Options > Menus WooCommerce not Found

Related posts: