By Melody Amsel-Arieli

Fans of fine cigars, like Cuban Habanos, Dominican Republic Alcántaras, or Mexican Gloria de Colóns, may not smoke them right away. Instead, many prefer to save them to celebrate special occasions like parties, birthdays, or anniversaries. Yet these rolled bundles of tobacco leaves, along with cigarettes and pipe tobacco, are produced in humid environments. Without proper storage, they dry out, lose their vital oils and nicotine content, turn sour, and burn quickly, unevenly, and hot on the palate. In fact, say some, cigars left in heated or air-conditioned rooms can dry out in under an hour. Those kept in properly maintained humidors, however, will, like fine wine, get richer in taste.

Storing tobacco products in humidors, moisture-controlled storage boxes, however, can preserve their long-term quality. They not only protect them from physical damage, but also shield them from direct heat or light. Ideally, all humidors maintain levels of 68 to 75 percent humidity. Lower amounts are ineffective, while higher amounts render cigars too soggy to smoke. Moreover, though cigars can be re-humidified after extensive periods of dryness, they will still taste stale.

Larger humidors mechanically maintain desired levels of humidity by pumping moisture from interior distilled water reservoirs. Smaller ones feature shallow pans of absorbent sponges, porous clays, and the like. As these become saturated, their water evaporates, releasing moisture into their interiors. Yet a combination of factors, like home heating or varying levels of humidity, may increase their rate of evaporation as well. In addition, humidity levels vary according to the number of cigars held. Fewer cigars increase moisture, while more cigars lower it. To combat changes, smokers often rely on decorative (though frequently inaccurate) hygrometers, round gauges with needles that gauge their humidity levels. If deemed necessary, they add or subtract appropriate amounts of distilled water.

By maintaining ideal temperatures from 12°C through 25°C, humidors prevent both cigar rot and hatchings of harmful tobacco beetles. Though interior linings vary, many feature rosy hued Spanish cedar, a soft, tight-grained, humidifying wood of the mahogany family commonly found in Central America. This material, in addition to its natural protective qualities, imbues cigars with a pleasant, slightly spicy aroma as they age.

The best humidors, as airtight as possible, feature perfectly fitted seals, flawlessly aligned hinges, and seamless corner joints. They must also “breathe.” So ideally, nothing should crowd them right, left, or from above.

Since cigar collections are often quite costly, better humidors may also feature locks. These offer protection from pinching the goods and prying eyes. After all, each time a humidor is opened, its humidity is affected.

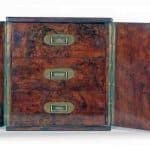

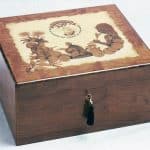

Vintage humidors varied greatly in size, depending on their function, contents, and the space needed for humidification and air circulation. Large multi-use floor models, like cabinets, tables, or coffee tables, might contain several thousand cigars. Desktop or mantelpiece models, the most popular types, held 25 to 500 cigars. These often featured special Spanish cedar trays with dividers, as well, which facilitated optimal use of space, allowed airflow, and eased organization.

Smaller, portable humidors, which were popular among consumers and collectors alike, allowed optimal separation of cigars according to age, flavor, aroma, and brand. Pocket ones, typically holding just two or three cigars and available in a variety of shapes and sizes, were often fashionable accessories.

The History

Humidors, like all tobacco products, were immensely popular from the early 1900s through the middle of the century. So their advertising, naturally, went hand in hand. A Cigars United advertisement in the 1906 Boston Globe, for instance, suggests “If your friend doesn’t own a humidor, send him one with a box of cigars inside it … Prices range from $3 for a humidor in plain design to $75 for ‘a thing of beauty and a joy forever.’ Rare woods and porcelains are handsomest [but] for $10 you can get a humidor any man will prize.”

A 1914 advertisement, featuring a Native American chief in full feathered regalia reads, “Prince Albert (the national joy smoke) makes the most peacefulest pipe smoke that you or any man can… roll into a makin’s [self-rolled] cigarette. … Buy a tidy red tinful … or, better yet, invest in the famous [Prince Albert] crystal-glass humidor with the sponge in the top …” Smokers evidently collected a variety of humidors.

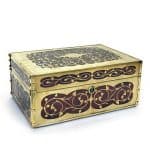

Today too, humidors remain highly collectible. Though most vintage models were made of decorative hardwoods like cherry, mahogany, or walnut, scores were also crafted in metal, glass, or pottery. Humidor shapes varied as well, ranging from classic squares and rectangles to slightly domed creations. Whimsical novelties, like a jaunty, be-spectacled, ceramic “Motorist” or a nautical-themed brass drum wrapped in braided rope, decorated with an anchor, and supported by a trio of cast metal paddles, were also very appealing.

Humidor styles, in response to market demand, often reflected fashionable artistic trends. Several exceptional examples are found in museums across the United States.

The Museum of Fine Arts, in Boston, MA, for instance, holds an extremely rare, unmarked, silver plate, rectangular model, possibly created by noted craftsmen Roswell Gleason and Sons, between 1851 through 1871 in Dorchester, MA. Its interior features a removable insert that holds cigarettes vertically, while its exterior features a shallow, horizontal shelf, likely for holding matches. It also features barred, bolted, cage-like addition that houses a pair of lean, silver plate greyhounds – possibly guard dogs? Without, a friendly spaniel attends a shawled visitor.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art in Pennsylvania holds a moss green, matte-glazed, stoneware humidor, part of its extensive Rookwood collection. In addition to luxurious Art Nouveau curved lines throughout, its lid features a freeform finial resembling a lithe, long-haired maiden. This museum also owns an early 20th century bronze humidor produced by Edward F. Caldwell & Company. It is bejeweled with gilt and champlevé enamel – hollow, metal enamelwork filled with multi-colored, repetitive enamel designs.

The Corning Museum of Glass, located in Corning, NY, boasts a sampling of distinctive humidors. Their opaque, mold-blown, cylindrical white glass one, created by Wave Crest of Meridien, CT, for example, dates to around 1900. In addition to a decorative brass “collar,” it features an enameled image of delicate pink flower sprays along with the label “Cigars.” Its lid, worked in a three-dimensional shell design, bears a similar spray.

Corning’s cylindrical humidor, crafted sometime between 1900 and 1910, is made of colorless, blown and cut lead glass. Along with a flat lipped rim, it features a hollow-stopper neck cut in historic star and diamond patterns. An intricate, multi-pointed hobstar, fan, and cane pattern adorns its sides and a cut star beautifies its base.

The Houston Museum of Fine Arts, based in Texas, boasts an unusual sterling silver Art Deco humidor, created in 1925, on the eve of the Great Depression. This restrained work, one of the last masterpieces of this genre by Tiffany & Co., features engravings of American Metal Company subsidiaries and workers at two of the company’s mines. Its lid, which depicts a miner chiseling ore from a rocky outcropping, and a steelworker pouring smoking, molten ore into a vessel, also glorifies United States physical labor.

The Pritzker Military Museum & Library, located in Chicago, offers very different sorts of vintage humidors, ones that apparently tempered the wages of war with the pleasures of a good smoke. One, constructed from several emptied 120 mm, brass and copper German artillery shells, features three decorative copper bands embellished with a handful of French coins, while another, made of a 20 mm naval shell, boasts a pair of decorative British coins. A squat, barrel-like model, made from wood encircled by a copper “stave,” features a cap made from part of a 77 mm artillery shell. Another Pritzker humidor, fashioned in France, bears the etching of a flower, alongside the poignant inscription, “Souvenir 1918.”

Tobacco use has dropped off considerably over the past decades. Yet many modern humidors, though likely less to entice serious collectors, are still the epitome of style. Top of the line, luxury models, for example, are fashioned from a variety of materials ranging from silver, malachite, goat skin, and buffalo hide to fine woods like Macassar ebony, evergreen, and rosewood. Some are enhanced with French marquetry, or soapstone, mother-of-pearl, bone, silver, brass, or tortoise shell inlay.

Those in the American Heritage Humidor Collection, which were manufactured in China for tobacco company Altadis in 1995, however, may be the most unusual contemporary humidors of all. These huge creations, made of resin composite and lined in cedar, replicate four of America’s most famous landmarks, The White House, the United States Capitol, the Jefferson Memorial, and the Lincoln Memorial. And they work too.

Melody Amsel-Arieli, an Israeli-American raised on a New Jersey farm, grew up amid cows, corn, and collectibles. In addition to writing countless magazine articles, she has also authored Between Galicia and Hungary: The Jews of Stropkov (Avotaynu) and Jewish Lives: Britain 1750-1950 (Pen & Sword). Visit her at amselbird.com

Photo’s courtesy bonhams.com, American Decorative Arts Curator’s Fund, Gerald and Virginia Gordon Collection, RubyLane, 1stdibs.com

Related posts: