by Maxine Carter-Lome

One of the earliest and simplest of tools known to man is the hand saw. Its use dates back to the Neolithic or later Stone Age (before the discovery of metals), when only the crudest of implements were constructed, making the hand saw a most primitive tool in all sense of the word. As man’s knowledge of metals increased, iron, copper, and bronze was used in tool construction, especially in the making of saws; however, it was the modern day industrialization of steel technology that greatly enhanced the use and effectiveness of hand saws.

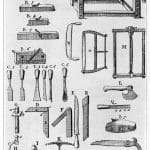

For the purposes of this article, a primitive hand saw is defined as a hand-crafted tool made in the 18th and early 19th century designed to cut primarily wood and other materials. At their most rudimentary level hand saws are comprised of a steel blade with either a sharp or ragged edge, a wooden handle or frame, saw nuts to affix the blade to the handle, and a maker’s mark or medallion.

The abundance and importance of wood for building, fuel, and as a source of income in 17th and 18th century America made the saw one of the most important tools in a colonist’s toolbox, and the sawmill one of a town’s first built structures. By the 1800s, almost every household owned a saw of some kind.

The ‘classic’ saw was seen as being ‘built to last,’ with a solid wooden handle and a blade able to be resharpened. Most were hand-crafted and designed to be passed through the family.

Types of early hand saws

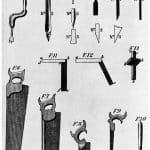

Ripsaws and handsaws (also known as “panel saws”) are used for general-purpose cutting of boards. Ripsaws were designed to cut with the grain, along the length of boards. Hand saws were slightly smaller and were used to cut both along and across the grain. Some examples of hand saws are the Artillery Saw, Chain Saw, and Portable Link Saw.

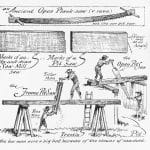

Cross-cut (or thwart) and pit saws are large, two-man versions of handsaws and ripsaws. Logs were cut to length with cross-cut saws and into boards with pit saws.

Compass saws had narrow, pointed blades that allowed them to be started through small drilled holes and expanded from there. They were used to cut holes in the middle of boards and to create pierced work such as chair splats.

Framed saws had their blades mounted inside wooden frames. The frames stretched the blade tight and allowed the use of longer, thinner blades. The bow saw was used by cabinetmakers and joiners to make curved cuts; the finer the work to be done, the finer the saw. Some frame saws are pieces of art both to work with and to look at.

The felloe, also known as the “chairmaker’s saw,” was used by wheelwrights for cutting the curved wooden segments of wheels and by chairmakers for sawing curved chair arms and legs. Felloe saws were one of the most specialized of all the hand saws, and were used at least until the 1890s.

Early American Makers

The earliest hand saws used in America came with settlers from their home country, and continued to be actively imported into this country up until the late 1800s. Most of these 17th and 18th century tools came from Sheffield, England, the main center of cutlery production in England from as early as 1600. A Sheffield hand saw was meant to work and meant to last; however, by the last decades of the 19th century American makers had overtaken the domestic market for hand saws. These companies and saw makers combined marketing with innovation and craftsmanship to create products that rivaled and later exceeded products coming from more traditional Sheffield saw makers. Here are a few to know:

Walter Cresson was an early Philadelphia saw maker in the 1840s and 50s who was bought out by Henry Disston at some point before the Civil War. His saws are characteristic of the early American style that drew heavily on English tool forms.

Henry Disston started making and selling saws in 1840, operating out of a rented basement in Philadelphia. Despite setbacks during his first decade in business, such as fires and the confiscation of his machinery in a rent dispute, Disston built his company into the largest manufacturer of saws in the world. Disston was an innovative manufacturer and marketer, eventually manufacturing everything from crosscut saws to rip saws. The company changed its name to Disston and Son in 1865. By using the medallion on the handle of a Disston saw you can identify the age of your saw.

Any of the saws with medallions from the 1840’s are great finds. A helpful resource to determine the age of your Disston saw can be found at: disstonianinstitute.com.

As far back as 1860, Elias C. Atkins received patents for sawblades and for the machines used for manufacturing saws. In 1885 Elias C. Atkins formed a partnership with W. Knippenberg to found E. C. Atkins & Co. The company went on to become a major American saw and tool manufacturer. Prior to 1893, the company concentrated on lumber, mill, and circular saws, of which they were a major player. Hand saws started to appear in the 1890’s catalogues. Today, E.C. Atkins & Co. is best known for making hand saws, circular saw blades and bandsaw blades, as well as grinders and cooperage machinery. Three styles of medallion nuts adorn E.C. Atkins’ products: the “inset AAA,” the middle period “AAA circular saw” logo, and the late-era “block text” logo.

The Richardson Brothers Saw Works company was established by Christopher and William C. Richardson in 1860 in Newark, New Jersey. The company started marking their products with a “Richardson Brothers” brand in the late 1870s. At that time they were producing a variety of tools, with saws being their main product. Christopher Richardson was a prolific innovator in the area of saw manufacture. He was granted nine patents. Among his innovations was a method to temper the steel used in the saw blade. This tempering process made a blade that cut better, stayed sharp longer, and was more durable. To this day their saws are highly sought by collectors and demand premium prices.

While old hand tools, especially saws, can be readily found at antique stores, country primitive shows, and flea markets, most are not worth much in terms of their continued use or value to a collector. There were several large makers and a much larger number of smaller companies making hand saws in America in the first half of the 19th century. For the beginner collector, brands such as Disston, Simonds, and Atkins, companies known for making high quality hand saws, are the brands worth looking for until you have the experience and confidence to pick out a good saw on the second hand market.

Each of these companies manufactured a “good-better-best” line of hand saws, identified by their product model names or numbers. If you are looking to collect, shoot for the best examples of the premium lines you can find. For example, for Disston, the #12 and #16 are recognized as top of the pack. The D8 is also a fine saw which is very common on the old tools market. Simond’s top quality saw was the #4. Also very good were the #4 1/2 and #5. Atkins’ premium handsaw was the #400, although the #68 was also very good. There are a number of books and websites on the Internet that can help identify the brand and product number, and often the year of manufacture by its medallion.

Next examine the blade. First and foremost, is it made of good quality steel and in good, used condition? Saws with blades made of the finest spring steel, properly tempered, provide the hardest and toughest blade possible. When looking at an antique saw, carefully inspect the blade. Unless you are looking for a decorative element for the barn wall or a rare saw to add to your collection, find a saw with the blade bright with no rust. More often, however you will encounter saws which have rust on them. While having rust does not mean the saw is no longer any good, if the rust is very thick and flaking, put it down. Light surface rust can be removed, the saw sharpened and set.

Lastly, look for unique saws such as a keyhole, compass or pruning saws. These intricate tools make interesting works of art with their blades, shape, and handle style.

Whether looking for vintage hand saws to restore and use, collect, or to turn into a piece of art, it’s clear that one of the oldest tools in our toolbox can still be put to good use.

Sources or this article include: history.org, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/hand_saw, The Saw in History, Henry Disston & Sons, 1916, Disston Saw Works, simondsint.com, timetestedtools.net, Ancient Carpenters’ Tools by Henry c. Mercer, Museum of Early American Tools.

Related posts: