By Erica Lome, Ph.D.

In the 1930s, no road trip across America was complete without a travel guide from the widely popular American Guide Series, published by the Federal Writers’ Project. Intended to stimulate the economy and boost national pride, these travel guides featured history-laden itineraries, photographs of major cultural icons, and directed access to new routes across the county. These highly collectible guides still retain their charm, especially Here’s New England: A Guide to Vacationland (1939). This volume, published to great success, is a fascinating artifact of the New Deal era and represents a bygone era of travel.

Establishment of the WPA

Starting early in his term as President amid the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt took measures to jumpstart relief for citizens, providing governmental aid for all facets of American life. The New Deal, as it was termed, continued to shore up the American lifestyle over the course of eight years.

After the initial efforts put forth, the Great Depression continued across the country, so in the spring of 1935, Roosevelt launched the Second New Deal (1935-1938) with the establishment of the Works Projects Administration (WPA) giving jobs to people related to federally sponsored projects that provided work for writers, artists, and photographers. The Federal Writers’ Project was part of the New Deal’s arts program known as Federal One. Headed by Henry Alsberg, its major claim to fame was the American Guide Series, which produced over four hundred travel guides to the states, major cities, highways, and regions of America.

The WPA employed 6,500 staff through state-sponsored programs to produce these guidebooks, and volumes were distributed to public schools, refugee centers, and libraries on military bases, as well as being prominently exhibited in bookshops, department stores, hotels, transportation depots, and advertisements. What made these guidebooks especially intriguing was that many of the contributors were anonymous, including photographers and essayists. By not allowing any one voice to dominate the tour’s narrative, popular opinion grew around the idea that these texts were truly democratic.

Road Trips to the Past

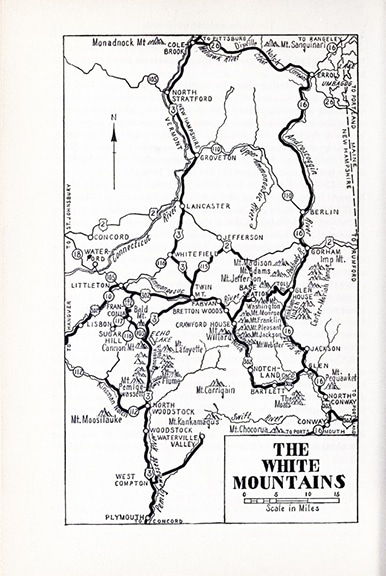

While many of the individual city and state entries of the American Guide Series emphasized industry, ethnic diversity, and modern architecture, those who worked on the regional and highway guides placed value in orienting citizens towards locating in the past what could be valuable in the present. The most vocal advocate for this agenda was Katherine Kellock, Tours Editor of the Federal Writers’ Project, who believed the road could carry important cultural images. She also fought for a more standardized approach for motor tours, establishing north-to-south and east-to-west rules. Kellock’s form is observable in how the tours were constructed, chopping up states to emphasize landscape features and allowing for a smooth and cohesive route from one destination to the next.

Published in Boston by Houghton Mifflin, Here’s New England was a regional guide featuring maps, images, itineraries, and thematic essays on the history and culture of each state. The dust jacket proclaimed: “This regional volume is unique in the series in that it covers more than one state. It would be useful to a traveler making an automobile tour of the New England region. It provides an excellent overview and includes some history, lore,

and photographs.”

The ease and accessibility of Here’s New England represented a transitional moment in how travel, and particularly driving, was being shaped in the 1930s. The Great Depression had made owning a car a necessary part of livelihood, allowing for families and migrant workers to find better opportunities out West. By 1931, there were fifty million automobiles produced, and by 1939 there were seventy-five million, with car ownership totaling twenty million by 1935. On the other hand, the country had about 500,000 miles of two-lane highways during the 1930s, and only about 70 percent of these were paved. The WPA ended up being responsible for over half a million miles of road construction during this period. Due to the migration of Americans west towards California, many viewed the road as a source of anxiety. In contrast, Here’s New England characterized the region as a place of safety, calling it “a great playland” for the traveler. This was reinforced by the reader’s first view of the book: the cover image depicted a log cabin, nestled by the sea with an island in the distance, and a white lighthouse welcoming in boats.

Here’s New England

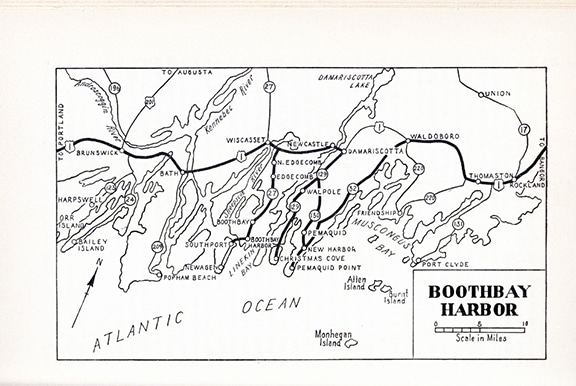

Here’s New England emphasized travel on new and expanded highway systems, such as US 1-7. US 1 dominated much of their journey, providing the main artery into the deep north of the region, and supplying them with an indelible natural icon of New England: the ocean. The chapter’s opening text elegantly stated, “Wherever you go—along the shore, around Great Bay, up the Piscataqua River, or among the tidewater streams—you can’t get away from the sea, for the whole region is as filled with the murmur of the waves as the conch you held to your ear when a child.” Driving north along the coast was an opportunity to connect with the earliest of the nation’s history, mediated through the seascape; that the books start with the sea and end inland was rooted in a paradigm of American progress. New England was linked with canonical maritime Americana symbols such as lighthouses, yachts, and Cape Cod Sandwich Glass.

With the ocean on one side and “rambling taverns” on the other, the New England tourist had a lot to see as they drove up US 1. The guide’s use of photography made these visual and impactful, and Here’s New England included over forty images from throughout the region. W. Lincoln Highton took most of the photographs, the remainder donated by state and historical societies. Highton served as the Chief Still Photographer for the U.S. Information Service in the late 1930s and populated numerous entries in the American Guide Series with his careful selections of images that invoked an idealized collective memory of national heritage. The photography of Here’s New England communicated what the traveler could see from the driver’s seat, and the introduction reminded travelers that the routes outlined allowed them to see many notable places in a particular sequence; deviation was unnecessary since the writers of the guides had already done all the hard work of sourcing the ideal itinerary, measuring out equal amounts of history, landscape, and architecture. The language of the guidebook appealed to this new breed of traveler, the “careful traveler,” who emerged out of the Great Depression and whose money and time had to be put to the best use. Here’s New England often didn’t mention specifically “driving” or putting forth any effort; rather phrases such as “this road will take you” or “you will then be brought” were utilized, as though the roads are in agreement with the guides in guaranteeing a safe and charming adventure.

Traveling Back in Time

The purpose of Here’s New England in all of this was to give middle-class Americans a chance to ‘discover’ pieces of the nation’s history in the small towns they passed through, with over seventy references to historic houses and museums. Facilitating this process were recently posted historic markers along roads which drew attention to local spots of importance, bringing awareness to drivers that the routes they were traveling could connect them to a larger national heritage. Yet Here’s New England, with its declarative and assertive title, was also notable for what it did not include for curious travelers. Despite the liberal agenda of the New Deal, this guidebook omitted any mention of African Americans, despite the long history of enslavement and abolition in the region. Similarly, the book ignored the continued presence of Native people in each state and instead leaned into the false mythology of the “vanishing Indian.” Instead, the guidebook celebrated the achievements of New England’s white, Anglo-American colonists and their descendants, figuratively gentrifying the region’s history for the enjoyment of tourists.

Here’s New England described the overall experience of travel through the region as going back in time. The further north you went, the more “antique” the landscape and towns became. The driver became a picker, choosing the best and most visually pleasing towns for their route. A traveler could pass through Guilford, Connecticut, “where there are preserved a larger number of authentic old houses than you’ll find in any New England town” or Gloucester, Massachusetts, “one American city where tradition has continued for three centuries.” The sacralization of American sites of historic importance was grasped by the entry to Plymouth and the South Shore, which was subtitled Pilgrim Shades and Shrines. The text stated: “The South Shore supports itself in diverse ways, but one thing its people have in common–the contented knowledge that they tread on hallowed ground, walking literally in the steps of their forefathers. They live in a region to which the rest of the nation makes its patriotic pilgrimage.” The “antique” designation for different New England towns extended even to their denizens, especially in states like New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine. For tourists, the occupants of these states were themselves an attraction, a phenomenon which lent itself to several humorous plays about rural Yankees encountering city slickers.

The Back-Roads

The “back-road” also played an interesting role in these guidebooks. Drivers certainly wanted to see these old roads as they journeyed through Vermont, but they didn’t necessarily want to be driving on them. The newly developed highway routes had standardized navigational geography, allowing for a sense of driver primacy, and situating those who drove as modern and progressive. At the same time, there was already a romantic nostalgia for the literal road less traveled. Here’s New England mediated this process by curating a visual experience for the car’s occupants. For example, rustic covered bridges became part of the “Vermont experience,” even though most were uncrossable; instead, they stood as proud icons of traditional craftsmanship and local history.

While the rise of recreational winter sports certainly had a hand in attracting visitors to New England, one anonymous author from Here’s New England summarized the real motivation for travelers: “A good many Americans turn, disillusioned, away from the future that wasn’t so near as they thought and perhaps was going to be very different from what they hoped, back towards the past still jogging with slow steadiness on its horse-and-buggy back-road way.” While one could not remain in Vacationland indefinitely, the Guide’s multiple routes, adventures, and itineraries allowed for New England to be viewed as a place of patriotic rejuvenation and a reminder of fundamental American values (as understood in the 1930s).

Although the Federal Writers’ Project dissolved in 1943, the popular American Guide Series continued to be reprinted long after. Yet, Here’s New England remains very much an artifact of its time, published to help citizens rekindle their love for America through interaction with historic house homes, lush landscapes, and quaint small towns. By approaching New England as a site of pilgrimage, readers could frame their vacations as an act of civic obligation, making automobiles and owning automobiles an indispensable aspect of true citizenship. Tourism linked these points together, stimulating local economies while projecting an image of the nation’s history that was enlightening, entertaining, and achievable. All you had to do was get in your car and go.

Related posts: