by Maxine Carter-Lome

In the first decades of the 20th century, nothing was more novel than the automobile. The idea of personal transportation with the freedom and ability to go where the road took you without all the limitations inherent in train travel was inspiring. Now, people could take motor trips in their leisure time just for the experience, setting the stage for a tourism movement driven by auto enthusiasts excited to see the country on their own terms.

The Outlook, a weekly magazine published in New York City from 1870-1935, was on the front lines of chronicling the rise of the automobile and auto tourism in America. In 1910, The Outlook reported that there were about 350,000 autos in use in America. Two years later, it proclaimed that the “automobile has changed interior traveling from a physical racking bore to a distinct frontier outing and a pleasure trip.” Colorado attorney Philip Delany wrote at the time, “The trails of Kit Carson and Boone and Crockett, and the rest of the early frontiersmen stretch out before the adventurous automobilist.”

Initially, it was only upper-class Americans who could afford the cost of an automobile, buying one mostly as a novelty and for entertainment and amusement purposes. Over the next decade, mass manufacturing and assembly line production reduced the cost of an automobile by roughly one-quarter from that of early 1900s pricing. The cost of an automobile was still more than the average American made in a year (the Model T was selling for $410 in 1914), but it was fast becoming a practical investment for a rising middle-class. By 1920, there were over 8 million automobile registrations in this country. A decade later, the number of registered drivers had almost tripled to 23 million. In just about 30 years, the automobile had gone from a novelty invention to a staple of American existence. So, where was everyone going in such a hurry?

Taking to the Road

The public was quick to recognize and embrace the recreational nature of the automobile, even in its earliest days. Like their pioneer forefathers, they saw it as a way to see and experience the country in a more up-close and personal way than train travel afforded. The automobile represented freedom, privacy, control, and adventure – attributes that resonated with Americans then, as it does with us today.

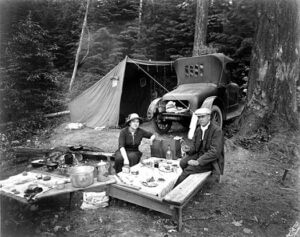

Automobilists could now take idle day trips into the countryside, stopping along the way for a picnic lunch at a picturesque spot. Those living in rural areas could now more easily drive to the nearest town or city to shop and bring goods to market. City dwellers could escape at their leisure the noise, grime, and chaos of urban life for the serenity and beauty of the great outdoors. Those looking west to find work and start a new life had a way to travel with their family and personal possessions. Visiting relatives and friends living far away was no longer an arduous journey but an experience, as was throwing your tent in the back seat and hitting the open road in search of a new adventure. We were a country on the move in the early 20th century, and the automobile was destined to take us where we were going, on our own terms.

Early Lodging Options

By 1930, over 23 million Americans had climbed into the driver’s seat. As they hit the open road to realize the American dream of seeing the country, fundamental roadblocks impeded their journey and threatened to derail an emerging auto tourism market. One problem they encountered was the condition and lack of roads to accommodate automobile travel. Roads would need to be built and paved to bring autoists into the country’s interior and help drive westward expansion. Another was that no national road system existed that linked the country coast-to-coast, and connected states with their neighbors. As a result, “autoists” had a difficult time navigating backroads and finding direct routes to help them find their way. And, with no hospitality and tourist infrastructure in place, motorists hit the open road not knowing when they would next find gas, a place to eat, and a suitable place to stay.

In the early days of auto touring people packed tents in their cars and pitched them by the side of the road when they got tired. By default, the farmer’s fields or lakeshores became known as “tourist camps.”

In the early 1920s, the demand by property owners to get auto tourists off of their land led to the creation of municipally-owned auto camps that provided parking space and limited services to autoists. Around 1923, the cost of providing attractive grounds and services, such as water and kitchen facilities, and eventually cottages, prompted municipal auto camps to begin charging fees, which also helped to keep out the “riff-raff” or “tin can” tourists that passed through the country during the Great Depression.

Rustic cabins were another early lodging option for autoists, providing guests a roof over their heads for a fee, and then charging extra for the mattress and bedding. These bare-bones shelters could be found by chance scattered along the rural highways of America, especially west of the Mississippi, but offered little comfort.

During the Depression, homeowners “let” out rooms in their homes or turned them into lodging establishments as a way to bring in extra money. Property owners whose land fronted the highway, built cabins along the road to convert unprofitable land into income.

Creative options were cropping up all over the country to accommodate overnight motorists outside of a city or town, but availability, suitability, and cost were inconsistent, especially as you traveled west. Lodging was more about shelter than a part of the travel experience. That was about to change with President Roosevelt’s second round of his “New Deal” in the 1930s which funded half a million miles of road construction to support the country’s westward and rural expansion. Regional guide books were published to help get auto tourists inspired to take road trips. But new roads and a guidebook only took the motor tourist so far. They would still need places to eat, stay, and get gas along the way.

The Evolution of the Motor Hotel

Starting in the 1930s, “cottage courts” (also known as “tourist courts”) emerged as a classier alternative to the rooms for let, dingy roadside cabins, and public auto camps, especially for the time for middle-class auto tourists.

Cottage courts were initially comprised of individual cottages arranged in a semicircle, centered by the manager’s office and surrounding a central lawn area where guests could mingle with other road travelers at the end of the day. This basic layout, more thoughtfully designed with the needs, privacy, comfort, and enjoyment of motorists in mind, helped to establish and standardize the look of “motel” lodging for the next half-century.

The term “motel” is said to have been first coined by the owner of the Milestone Mo-Tel (an abbreviation of “motor hotel”), built in 1925 in San Luis Obispo, California. The term quickly caught on and soon became the catch-all word for the cottage court model and its future iterations; a word still used today to describe “a roadside hotel designed primarily for motorists, typically having the rooms arranged in a low building with parking directly outside.”

In the evolution of the tourist-court-turned-motel, guest cabins went from basic, independent structures to individual, private rooms fully integrated under a single roof in a basic U- or L-shaped layout, with the manager’s office in the middle and the rooms surrounding a central courtyard facing the road. Added amenities such as a swimming pool or playground, and landscaping that evoked a resort- or park-like setting, were designed to capture the attention and advertise the motel’s desirability to passing motorists.

The Post-War Motel Boom

During the War years, few Americans had the time to indulge in tourist travel with the men away at war and the women holding down jobs on the home-front in their absence, but the desire to hit the open road was only on idle. It took the end of WW II to shift auto tourism into second gear. New car sales quadrupled between 1945 and 1955, and by the end of the 1950s, some 75 percent of American households owned at least one car.

President Eisenhower instituted the Interstate Highway System in 1956 and Americans were buying automobiles and hitting the road like never before. Traveling by car to see the country and connect with our national heritage re-emerged as a patriotic movement. New roads were built, automobiles became more affordable, guidebooks to historic and natural sites were published, family-friendly tourist attractions emerged, and motels, diners, and gas stations cropped up everywhere along the way. Hitting the open road to “See the USA in your Chevrolet” was how all Americans, especially a rising middle class with more leisure time, discretionary income, and mobility, could do their part in our nation’s post-war economic recovery.

Similar to the evolution of towns that sprung up in the late 19th century around railroad stops to accommodate the needs of captive riders, strips of motels in the middle of nowhere caused whole towns to spring up and put new tourist destinations on the map. Motels opened near major freeway interchanges, tourist attractions, airports, outside of rural towns and cities as a more affordable and private alternative to city hotels and small-town lodging establishments. By 1950, there were 50,000 motels in the U.S. serving half of the 22 million vacationers out on the road, traveling the country.

Standing Out from the Crowd

Motels began to increase their capacity and revenue abilities by adding additional floors to their structure, expanding public interior space to include meeting rooms and banquet facilities, and adding restaurants, coffee shops, and gift shops to provide guests with added amenities and a more attractive alternative to another motel down the road.

It took less than half a century for roadside lodging to go from rustic and hard-to-find to over-saturated, especially along some of the more popular auto travel routes that were cropping up across the country. Now, motel and lodging owners needed to work for the customer’s attention.

To attract the attention of post-war travelers who now had a choice, many motel operators turned to neon road signs and kitschy themes tied to roadside attractions. They created theme cottages like “rustic” or “western,” and rooms built to resemble a country cottage or a concrete tepee appropriated from Native American culture. The manager’s office and sign began to take on more ostentatious forms, as did the signs that started dotting the roadside landscape directing travelers where to go.

Mid-century motels styled themselves as roadside resorts, offering luxuries previously available only at expensive hotels, like swimming pools. This was also the age of the “Tiki” craze, inspired by soldiers returning from the Pacific theater of World War II. Motel owners built huge, culturally insensitive depictions of Polynesian gods that loomed over pools and restaurant buffets. Native American-themed motels were also plentiful.

From One-of-a-Kind to a Recognized Haven

With motel-type establishments now an expected part of the tourist experience, motel chains were in a position to gain the upper hand by offering travelers a recognized place to stay in a sea of the unknown.

Many of the earliest motel chains were tied to a single ownership group operating under a common brand across properties. These hotels were designed to look the same and provide a consistent guest experience. Alamo Plaza Hotel Courts, founded in 1929 in East Waco, Texas, was one of the earliest motel chains in the country with seven motor courts by 1936 and more than twenty by 1955. With Simmons furniture, Beautyrest mattresses on every bed, and telephones in every room, the Alamo Plaza rooms were marketed as “tourist apartments” under a slogan of “Catering to those who care.”

In 1935, building contractor Scott King opened King’s Motor Court in San Diego, California, renaming the original property Travelodge in 1939 and extending the name to the two dozen more similarly-designed motel-style properties he built over the next five years. Travelodge is still a recognized name to look for when on the road among auto tourists.

With demand growing, especially after the war, franchising became the key to funding the development and expansion of conveniently-located properties. Mom and pop motel owners were either being bought out for their location and existing facility, or driven out of the market by the brand motels that started dominating the roadside landscape. The days of unique and quirky were over. The experience now was all about consistency, comfort, and amenities.

National Brand-Building

In 1951, residential developer Kemmons Wilson turned a problem he experienced on a road trip—inconsistent accommodations—into the first Holiday Inn motel. which he opened on Route US 70 from Memphis to Nashville. He adopted the name from the 1942 musical film, Holiday Inn. Every new Holiday Inn would have TV, air conditioning, a restaurant, and a pool; all would meet a long list of standards so a guest in Memphis would have the same experience as someone in Daytona Beach, Florida, or Akron, Ohio. Holiday Inn was first to deploy an IBM-designed national room reservations system in 1965 and opened its 1000th location by 1968.

An example of growing another national chain for travelers started in 1925 when Howard Deering purchased a small corner pharmacy in Quincy, Massachusetts. Deering devised a new ice cream that would make his recently installed soda fountain the busiest part of his drugstore. The new recipe which contained increased butterfat made his new Howard Johnson’s ice cream more flavorful and a hit with customers. The popularity of Howard Johnson’s ice cream inspired Johnson to open franchised restaurants that would feature his ice cream and offer roadside favorites such as fried clams, baked beans, chicken pot pies, frankfurters, and soft drinks. By 1954, there were 400 Howard Johnson’s restaurants in 32 states. This was one of the first nationwide restaurant chains. They were ideally positioned, by location and brand awareness, to branch out into the lodging business.

In 1954, the company opened the first Howard Johnson’s motor lodge in Savannah, Georgia. The company employed architects to oversee the design of the rooms and gate lodge to integrate their motel into the look, color, and design of the now well-known Howard Johnson’s restaurants. When Howard Johnson Company went public in 1961, there were 88 franchised Howard Johnson’s motor lodges across 32 states.

While the number of motels in the United States reached a peak of 61,000 establishments in 1964, the decline in the last half-century has been steady, and can be attributed to the rise and proliferation of brand hotels, and more recently, the Internet, where travelers can instantly compare options before they hit the road, from price to amenities, and read the feedback from previous guests. Yet, for all their kitchy-ness, dated appeal, and rustic charm, motels remain a part of our 20th century landscape and childhood travel memories. As reminders, we cherish everything from motel ashtrays and embroidered towels to menus, placements, postcards, tableware, roadside souvenirs, and everything else we picked up and experienced along the way.

Related posts: