Home Sweet Home – American Folk Art Museum – The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles – January 2002

Two school diplomas and a university degree were my reward for serving to seventeen years in the trenches of formal education. Names, dates, facts, philosophies, had been retained dutifully in my mind, but at the age of twenty-two I remained out of focus about myself and a career. My solution was to step off the whirring carousel, walk away from the familiar, and gain new perspectives.

And for two years I lived and taught school in Athens. Coming from New York, city of energy and modernity, I needed the contrast of Greece with her ancient culture that had provided the foundations of Western art and governance. If America was the apex of current civilization, then Greece contained its primitive and uninhibited beginnings.

During my weekend travels away from the Byzantine cities and towns, pockets of the Grecian landscape seemed absolutely unchanged from ancient times. On two occasions, in the Peloponnesus and along the Mani coast, I remember walking alone – not a scrap of paper or rusty beer can, no jet stream painting the sky, not even the sputtering motor of a caique. There wasn’t one reminder of the twentieth century. I was walking on rocky terrain – broken only by the occasional olive tree – whose worn patina bore witness to life in antiquity. Across the water, silhouetted against a timeless twilight backdrop, the wavy coastline appeared trampled and beaten down by centuries of human activity. Soldiers, sailors, farmers, and shepherds, plying land and sea millenniums ago, passed before me on the stark stage. Isolated in this ancient landscape, I was indeed a New York Yankee in Homer’s Hellas, but this was no sleep, this was no dream.

Call it an awakening, at once very spiritual and physical. A new set of muscles was born and stretched, totally independent of my academic intellect, which had labored for so long in classrooms to appreciate history. Being on location with sights and sounds gave a vital life force to what the mind had learned long ago. The image of the land, that earth so essential to the beginnings of Western civilization, had touched me and reached my core. During my stay in Athens I collected shards and pieces of ancient pottery as away of marking those special moments in the Greek countryside. Baked earth, shaped and decorated by human hands, underlined the basic working relationship between nature and man.

NEW YORK, 1964

For fear of becoming an expatriate, I returned to America in the summer of 1964. As it always has, the visual impact of the city skyline stunned me as I crossed the Triborough Bridge on my way home to New York. The thrust of the gateway city’s creativity and energy, so neatly packaged in buildings and the grid, underline the unique standing America has in human history. where the worn and crusty earth of a Greek landscape had served me as a marker for the beginnings of our civilization, so the towering skyscrapers symbolized a country that has created opportunity and government for a vast population as no previous society has been able to do.

Having lived and worked overseas for two years, I had gained a different perspective on Ametica. It was the center of the world, a cultural and material force to be envied and hated, to be loved and pursued as an earthly paradise for humanity. In such a short, histotical time-two hundred and fifty years-this community had grown from immigrant seeds to become a national entity that reached out to the world and spread its culture.

History books had taught me the names of heroes and the principles of independence and representation. But the day-to-day work and settlement of this land had been in the hands of unknown soldiers and fami-lies, farmers and tradespeople. I had never been told their story. Tools, tableware, bedcovers, birth certificates – what survives today from those pioneers who laid the foundations for the society in which I live, for the civilization that is so special in human history?

This article is reprinted from American Radiance by permission of Abrams Publishing and The American Folk Art Museum.

Photos courtesy of Abrams and AFAM.

One week back from Athens and I realized that my great friend June Ewing had an upcoming birthday for which I was totally unprepared. With four children and an open door of welcome to friends and animals, June lived with country furniture and pieces that created a warm atmosphere of comfort and simplicity. Having grown up in a very French eighteenth-century apartment environment and the accompanying discipline of scheduled meals and guests, I had been immediately seduced by June’s naturalness and humanity. It had always seemed obvious to me that the Early American furnishings in her homes were an automatic by-product of her character and sensibilities.

My immediate need on that humid July day was to find a good present; an article in the newspaper directed me to anew folk art gallery on Fifty-seventh Street. I spotted a colorful coverlet and bought it. Awaiting my change and the gift-wrapped package, I looked around: there on a battered tavern table was a small slipware dish ( see bottom right). “Pennsylvania German,” said the dealer, noticing my fascination. I turned it over, and once again, there was the earth, the rough underside providing such a contrast to the smooth slip surface. No mistaking this piece for my antique shards.

Time had barely touched the veneer of this plate compared to the millenniums Greek pottery had survived. Fired over a century ago, the neon glitter of the Pennsylvania slip seemed positively modern compared to its ancient counterpart. Yet, it too was an artifact, a survivor of a great culture. In the end, I walked out with two purchases: a bulky birthday gift to be carried and a piece of Pennsylvania earth slipped into my pocket. My American journey had begun.

-Ralph Esmerian

On Tuesday morning, December 11th, the new home of the American Folk Art Museum opened to the public to strains of “When The Saints Go Marchin’ In” performed by a live band. The latest addition to the 53rd Street’s Museum Row, including MOMA, The American Craft Museum, and the 52nd Street Museum of Television and Radio, houses a superb collection of Americana. The eight level, 30,000 square-foot building at 45 West 53rd Street fulfills the Museum’s goal of establishing a permanent home for the study and appreciation of American folk art.

The first series of exhibits are titled American Anthem. Currently on display is American Anthem Part I which includes American Radiance: The Ralph Esmerian Gift to the American Folk Art Museum and DARGER: The Henry Darger Collection.

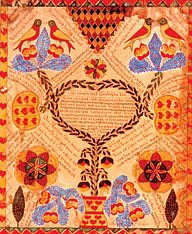

American Radiance displays some of the best that American folk art of the 18th and 19th centuries has to offer. Fabulous groupings of sophisticated needleworks, portraiture, scrimshaw, Shaker and fraktur dominate three exhibit floors.

A few stellar pieces, such as an early 1800’s round document box trunk ( see bottom right) with hand-painted interior and a massive door from the Cornelius Couvenhoven house, circa 1850, are sprinkled throughout. Two pieces in particular; a wooden model of The Empire State building done in 1931 by an ironworker who was employed in the construction of that edifice and a painted wooden panel entitled “The Situation of America” (above) New York, 1848, clearly a depiction of the young republic in her first highly-prosperous decade, emerge distinctly in the aftermath of September 11th.

Maybe it is healthy for all of us to review our glorious heritage depicted in the fine exhibit and in so doing, to carry on accordingly into our future.

-Nansi Nelson

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”SearchAndAdd” width=”550″ height=”200″ title=”American Folk Art” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” keywords=”American Folk Art” browse_node=”” search_index=”Books” /]

Related posts: