By Selena McGonnell, MSc Museum Studies, BS History

The 20th century brought with it many new female art collectors and patrons. They made numerous significant contributions to the art world and museum narrative, acting as tastemakers to the 20th-century art scene and their society. Many of these women’s collections served as a foundation for present-day museums. Here are ten art collectors who made a name for themselves within the art historical narrative:

Helene Kröller-Müller: One of the Netherland’s Finest Art Collectors

The Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands boasts the second-largest collection of van Gogh works outside of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, as well as being one of the first modern art museums in Europe. There would be no museum if it were not for the efforts of Helene Kröller-Müller.

Upon her marriage to Anton Kröller, Helene moved to the Netherlands and was a mother and wife for over 20 years before she took an active role in the art scene. Evidence suggests her initial motivation for her art appreciation and collecting was to distinguish herself in Dutch high society, which allegedly snubbed her for her nouveau riche status.

In 1905 or ‘06 she started taking art classes from Henk Bremmer, a well-known artist, teacher, and advisor to many art collectors in the Dutch art scene. It was under his guidance that she began collecting, and Bremmer served as her advisor for more than 20 years.

Kröller-Müller collected contemporary and Post-Impressionist Dutch artists, and developed an appreciation for van Gogh, collecting approximately 270 paintings and sketches. Though her initial motivation seems to have been to show off her taste, it was clear in the early stages of her collecting and letters with Bremmer that she wanted to build a museum to make her art collection accessible to the public.

When she donated her collection to the State of the Netherlands in 1935, Kröller-Müller had amassed a collection of nearly 12,000 works of art, showcasing an impressive array of 20th-century art, including works by artists of the Cubist, Futurist, and Avant-garde movements, like Picasso, Braque, and Mondrian.

Mary Griggs Burke: Collector and Scholar

It was her fascination with her mother’s kimono that started it all. Mary Griggs Burke was a scholar, artist, philanthropist, and art collector. She accumulated one of the largest collections of East Asian Art in the United States and the largest collection of Japanese art outside of Japan.

Burke developed an appreciation for art early in life; she received art lessons as a child and took courses on art technique and form as a young woman. Burke began collecting while still in art school when her mother gifted her a Georgia O’Keefe painting, The Black Place No. 1. According to a biography, the O’Keefe painting greatly influenced her taste in art.

After she married, Mary and her husband traveled to Japan where they collected extensively. Their taste for Japanese art developed over time, narrowing their focus to form and complete harmonies. The collection contained many excellent examples of Japanese art from every art medium, from Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, and screens, to ceramics, lacquer, calligraphy, textiles, and more.

Burke had a genuine passion for learning about the pieces she collected, becoming more discerning over time through working with Japanese art dealers and prominent scholars of Japanese art. She developed a close relationship with Miyeko Murase, a prominent professor of Asian Art at Columbia University in New York, who provided inspiration for what to collect and helped her understand the art. He persuaded her to read Tale of the Genji, which influenced her to make several purchases of paintings and screens depicting scenes from the book.

Burke was a steadfast supporter of academia, working closely with Murase’s graduate teaching program at Columbia University; she provided financial support to students, held seminars, and opened her own homes in New York and Long Island to allow the students to study her art collection. She knew that her art collection could help improve the academic field and discourse, as well as improve her understanding of her own collection.

When she died, she bequeathed half of her collection to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the other half to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, her hometown.

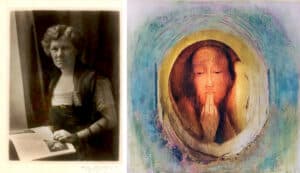

Katherine S. Dreier: 20th-Century Art’s Fiercest Champion

Katherine S. Dreier is best known today as the tireless crusader and advocate for modern art in the United States. Dreier immersed herself in art from an early age, training at the Brooklyn Art School, and traveling to Europe with her sister to study Old Masters.

It was not until 1907-08 that she was exposed to modern art, viewing the art of Picasso and Matisse in the Paris home of prominent art collectors Gertrude and Leo Stein. She began collecting soon after in 1912, having bought Van Gogh’s, Portrait de Mlle. Ravoux, at the Cologne Sonderbund Exhibition, a comprehensive showing of European Avant-garde works.

Her painting style developed along with her collection and dedication to the modernist movement thanks to her training and the guidance of her friend, prominent 20th-century artist Marcel Duchamp. This friendship solidified her dedication to the movement and she began to work to establish a permanent gallery space in New York, dedicated to modern art. During this time, she was introduced to and collected the art of international and progressive Avant-garde artists like Constantin Brâncuși, Marcel Duchamp, and Wassily Kandinsky.

She developed her own philosophy that informed how she collected modern art and how it should be viewed. Dreier believed “art” was only “art” if it communicated spiritual knowledge to the viewer.

With Marcel Duchamp and several other art collectors and artists, Dreier established Société Anonyme, an organization that sponsored lectures, exhibitions, and publications dedicated to modern art. The collections they exhibited were mostly 20th-century modern art, but also included European post-impressionists like Van Gogh and Cézanne.

With the success of the exhibitions and lectures of Société Anonyme, the idea of establishing a museum dedicated to modern art transformed into a plan to create a cultural and educational institution dedicated to modern art. Due to a lack of financial support for the project, Dreier and Duchamp donated the bulk of Société Anonyme’s collection to the Yale Institute of Art in 1941, and the rest of her art collection was donated to various museums upon Dreier’s death in 1942.

Though her dream to create a cultural institution was never realized, she will always be remembered as the fiercest advocate of the modern art movement, creator of an organization that predated the Museum of Modern Art, and donor of a comprehensive collection of 20th-century art.

Lillie P. Bliss: Collector and Patron

Best known as one of the driving forces behind the establishment of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Lizzie P. Bliss, known as Lillie, was one of the most significant art collectors and patrons of the 20th century.

Born to a wealthy textile merchant who served as a member of President McKinley’s cabinet, Bliss was exposed to the arts at an early age. Bliss was an accomplished pianist, having trained in both classical and contemporary music. Her interest in music was her initial motivation for her first stint as a patron, providing financial support to musicians, opera singers, and the then-fledgling Julliard School for the Arts.

Like many other women on this list, Bliss’ tastes were guided by an artist advisor, and Bliss became acquainted with the prominent modern artist Arthur B. Davies in 1908. Under his tutelage, Bliss collected mainly late 19th to early 20th century Impressionists’ work from artists such as Matisse, Degas, Gauguin, and Davies.

As part of her patronage, she contributed financially to Davies’ now-famous Armory show of 1913 and was one of many art collectors who loaned her own works to the show. Bliss also bought around 10 works at the Armory Show, including works by Renoir, Cézanne, Redon, and Degas.

After Davies died in 1928, Bliss and two other art collectors, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and Mary Quinn Sullivan, decided to establish an institution dedicated to modern art.

In 1931 Lillie P. Bliss died, two years after the opening of the Museum of Modern Art. As part of her will, Bliss left 116 works to the museum, forming the foundation of the art collection for the museum. She left an exciting clause in her will, giving the museum the freedom to keep the collection active, stating that the museum was free to exchange or sell works if they proved vital to the collection. This stipulation allowed for many important purchases for the museum, particularly the famous Starry Night by van Gogh.

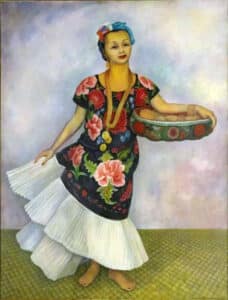

Dolores Olmedo: Diego Rivera Enthusiast and Muse

Dolores Olmedo was a fierce self-made Renaissance woman who became a great advocate for the arts in Mexico. She is best known for her immense collection and friendship with the prominent Mexican muralist, Diego Rivera.

Along with meeting Diego Rivera at a young age, her Renaissance education and the patriotism instilled in young Mexicans after the Mexican Revolution greatly influenced her collecting tastes. This sense of patriotism at an early age was probably her initial motivation to collect Mexican art and later advocate for Mexican cultural heritage, as opposed to the selling of Mexican art abroad.

Rivera and Olmedo met when she was around 17 when she and her mother were visiting the Ministry of Education while Rivera was there after being commissioned to paint a mural. Diego Rivera, already an established 20th-century artist, asked her mother to allow him to paint her daughter’s portrait.

Olmedo and Rivera maintained a close relationship throughout the rest of his lifetime, with Olmedo appearing in several of his paintings. In the last years of the artist’s life, he lived with Olmedo, painting several more portraits for her, and made Olmedo the sole administrator of both his wife and fellow artist’s estate, Frida Kahlo. They also made plans to establish a museum dedicated to Rivera’s work. Rivera advised her on which works he wanted her to acquire for the museum, many of which she bought directly from him. With close to 150 works made by the artist, Olmedo is one of the largest art collectors of Diego Rivera’s artwork.

She also acquired paintings from Diego Rivera’s first wife, Angelina Beloff, and around 25 works of Frida Kahlo’s. Olmedo continued to acquire artwork and Mexican artifacts until the Museo Dolores Olmedo opened in 1994. She collected many works of 20th-century art, as well as colonial artwork, folk, modern and contemporary.

Countess Wilhelmina Von Hallwyl: Collector of Anything and Everything

Outside of the Swedish Royal family, Countess Wilhelmina von Hallwyl amassed the largest private art collections in Sweden.

Wilhelmina began collecting at an early age with her mother, first acquiring a pair of Japanese bowls. This purchase started a lifelong passion for collecting Asian art and ceramics, a passion she shared with Sweden’s Crown Prince Gustav V. The royal family made it fashionable to collect Asian art, and Wilhelmina became part of a select group of Swedish aristocratic art collectors of Asian art.

Her father, Wilhelm, made his fortune as a timber merchant, and when he died in 1883, he left his entire fortune to Wilhelmina, making her independently wealthy from her husband, Count Walther von Hallwyl.

The Countess bought well and widely and collected everything from paintings, photographs, silver, rugs, European ceramics, Asian ceramics, armor, and furniture. Her art collection consists of mainly Swedish, Dutch, and Flemish Old Masters.

From 1893-98 she built her family’s home in Stockholm, keeping in mind that it would also serve as a museum to house her collection. She was also a donor to several museums, most notably the Nordic Museum in Stockholm and the National Museum of Switzerland, after completing archaeological excavations of her Swiss husband’s ancestral seat of Hallwyl Castle. She donated the archaeological finds and furnishings of Hallwyl Castle to the National Museum of Switzerland in Zurich, as well as designed the exhibition space.

By the time she donated her home to the State of Sweden in 1920, a decade before her death, she amassed around 50,000 objects in her home, with meticulously detailed documentation for each piece. She stipulated in her will that the house and displays must remain essentially unchanged, giving visitors a glimpse into early 20th-century Swedish nobility.

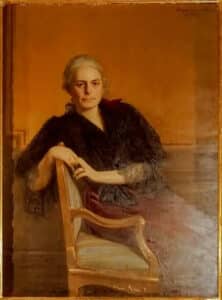

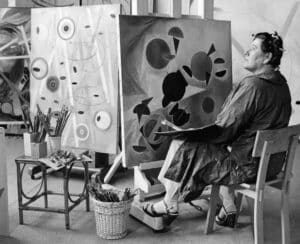

Baroness Hilla Von Rebay: Non-Objective Art’s “It Girl”

Artist, curator, advisor, and art collector, Countess Hilla von Rebay played an essential role in the popularization of abstract art and ensured its legacy in 20th century art movements.

Born the Hildegard Anna Augusta Elisabeth Freiin Rebay von Ehrenwiesen, known as Hilla von Rebay, she received traditional art training in Cologne, Paris, and Munich, and began to exhibit her art in 1912. While in Munich, she met artist Hans Arp, who introduced Rebay to modern artists like Marc Chagall, Paul Klee, and most importantly, Wassily Kandinsky. His 1911 treatise, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, had a lasting impact on both her art and collecting practices.

Kandinsky’s treatise influenced her motivation to create and collect abstract art, believing that non-objective art inspired the viewer to search for spiritual meaning through simple visual expression.

Following this philosophy, Rebay acquired numerous works by contemporary American and European abstract artists, such as the artists mentioned above and Bolotowsky, Gleizes, and in particular Kandinsky and Rudolf Bauer.

In 1927, Rebay immigrated to New York, where she enjoyed success in exhibitions and was commissioned to paint the portrait of millionaire art collector Solomon Guggenheim.

This meeting resulted in a 20-year friendship, giving Rebay a generous patron which allowed her to continue her work and acquire more art for her collection. In return, she acted as his art advisor, guiding his tastes in abstract art and connecting with the numerous avant-garde artists she met over her lifetime.

After amassing a large collection of abstract art, Guggenheim and Rebay co-founded what was previously known as the Museum of Non-Objective Art, now the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, with Rebay acting as the first curator and director.

Upon her death in 1967, Rebay donated around half of her extensive art collection to the Guggenheim. The Guggenheim Museum would not be what it is today without her influence, having one of the largest and best quality art collections of 20th-century art.

Peggy Cooper Cafritz: Patron of Black Artists

in New York in 2017

There is a distinct lack of representation of artists of color in public and private collections, museums, and galleries. Frustrated by this absence of equity in American cultural education, Peggy Cooper Cafritz became an art collector, patron, and fierce education advocate.

From an early age, Cafritz was interested in art, starting from her parents’ print of Bottle and Fishes by Georges Braque and frequent trips to art museums with her aunt. Cafritz became an advocate for education in the arts while in Law school at George Washington University. She began collecting as a student at George Washington University, purchasing African masks from students who came back from trips to Africa, as well as from a well-known collector of African art, Warren Robbins. While in law school, she was involved in organizing a Black Arts Festival, which developed into the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington D.C.

After law school, Cafritz met and married Conrad Cafritz, a successful real estate developer. She stated in the autobiography essay in her book, Fired Up, that her marriage afforded her the ability to begin collecting art. She started out collecting 20th-century artworks by Romare Bearden, Beauford Delaney, Jacob Lawrence, and Harold Cousins.

Over a 20-year period, Cafritz collected artwork that aligned with her social causes, gut feelings towards artwork, and a desire to see Black artists and artists of color permanently included in art history, galleries, and museums. She recognized that they were woefully missing in major museums and art history.

Many of the pieces she collected were contemporary and conceptual art and she appreciated the political expression they exuded. Many of the artists she supported were from her own school, as well as many other BIPOC creators, such as Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Titus Raphar, and Tschabalala Self to name a few.

Unfortunately, a fire devastated her D.C. home in 2009, resulting in the loss of her home and over 300 works of African and African American artwork, including pieces by Bearden, Lawrence, and Kehinde Wiley.

Cafritz rebuilt her collection, and when she passed in 2018, she divided her collection between the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Duke Ellington School of Art.

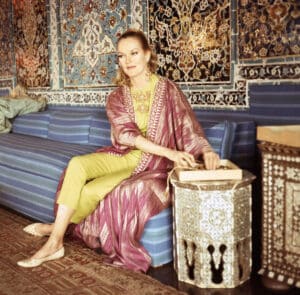

Doris Duke: Collector of Islamic Art

Once known as “the richest girl in the world,” art collector Doris Duke amassed one of the largest private collections of Islamic art, culture, and design in the United States.

Her life as an art collector began while on her first honeymoon in 1935, spending six months traveling through Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. The visit to India left a lasting impression on Duke, who enjoyed the marble floors and floral motifs of the Taj Mahal so much that she commissioned a bedroom suite in the Mughal style for her home.

Duke narrowed her collecting focus to Islamic art in 1938 while on a buying trip to Iran, Syria, and Egypt, arranged by Arthur Upham Pope, a scholar of Persian art. Pope introduced Duke to art dealers, scholars, and artists who would inform her purchases, and he remained a close advisor to her until his death.

For nearly 60 years Duke collected and commissioned approximately 4,500 pieces of artwork, decorative materials, and architecture in Islamic styles. They represented the Islamic history, art, and cultures of Syria, Morocco, Spain, Iran, Egypt, and Southeast and Central Asia.

Duke’s interest in Islamic art could be seen as purely aesthetic or scholarly, but scholars argue that her interest in the style was right on track with the rest of the United States, which seemed to partake in a fascination of “the Orient.” Other art collectors were also adding Asian and Eastern art to their collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with whom Duke was often rivaled for collection pieces.

In 1965, Duke added a stipulation in her will, creating the Doris Duke Foundation for the Arts, so her home, Shangri La, could become a public institution dedicated to the study and promotion of Middle Eastern art and culture. Nearly a decade after her death, the museum opened in 2002 and continues her legacy of the study and understanding of Islamic art.

Gwendoline and Margaret Davies: Welsh Art Collectors

Through their industrialist grandfather’s fortune, the Davies sisters solidified their reputation as art collectors and philanthropists who used their wealth to transform areas of social welfare and the development of the arts in Wales.

The sisters started collecting in 1906, with Margaret’s purchase of a drawing of An Algerian by HB Brabazon. The sisters began to collect more voraciously in 1908 after they came into their inheritance, hiring Hugh Blaker, a curator for the Holburne Museum in Bath, as their art advisor and buyer.

The bulk of their collection was amassed over two periods: 1908-14, and 1920. The sisters became known for their art collection of French Impressionists and Realists, like van Gogh, Millet, and Monet, but their clear favorite was Joseph Turner, an artist of the Romantic style who painted land and seascapes. In their first year of collecting, they bought three Turners, two of which were companion pieces, The Storm and After the Storm, and bought several more throughout their lives.

They collected on a lesser scale in 1914 due to WW1, when both sisters joined in the war effort, volunteering in France with the French Red Cross, and helping to bring Belgian refugees to Wales.

While volunteering in France they made frequent trips to Paris as part of their Red Cross duties, while there Gwendoline picked up two landscapes by Cézanne, The François Zola Dam and Provençal Landscape, which were the first of his works to enter a British collection. On a smaller scale, they also collected Old Masters, including Botticelli’s Virgin and Child with a Pomegranate.

After the war, the sisters’ philanthropic pursuits were diverted from art collecting to social causes. According to the National Museum of Wales, the sisters hoped to repair the lives of traumatized Welsh soldiers through education and the arts. This idea spawned the purchase of Gregynog Hall in Wales, which they transformed into a cultural and educational center.

In 1951 Gwendoline Davies died, leaving her part of their art collection to the National Museum of Wales. Margaret continued acquiring artwork, mainly British works collected for the benefit of her eventual bequest, which passed to the Museum in 1963. Together, the sisters used their wealth for the wider good of Wales and completely transformed the quality of the collection at the National Museum of Wales.

McGonnell, Selena. “10 Prominent Female Art Collectors of the 20th Century” TheCollector.com, https://www.thecollector.com/20th-century-female-art-collectors/ (accessed February 27, 2021). Selena McGonnell is a contributing writer and museologist. She holds an MSc in Museum Studies from the University of Glasgow, and a BS in History. She has a passion for museums and heritage with research interests in collections of colonial context, curatorial practices, art provenance, and British history.

Related posts: