By Patricia H. Svoboda, Research Coordinator, Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Gallery.

Reprinted with permission.

oil on canvas, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, Bequest of Erskine Hewitt

Portrait of Sarah Cooper Hewitt in French Costume, by J. Carroll Beckwith, 1899, pastel crayon on paper mounted on linen Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, Bequest of Erskine Hewitt

As collectors, patrons, and museum founders, American women have played an influential role in national and international art circles from the late nineteenth century until today. With the rise of first-wave feminism, women acquired greater financial independence and access to education and professional careers. They also gained confidence in visiting galleries and museums and participating in cultural organizations. In turn, women commissioned and acquired fine art and decorative objects directly from the artists, or through dealers and commercial galleries. Some even went on to found museums in an effort to share their collections with broader audiences.

From the 1890s to the 1920s, these female patrons were quintessential “New Women.” The author Henry James popularized the term, which referred to the growing number of feminists who made their presence felt in cultural, educational, and political groups. Active in the suffragist cause, they exhibited their art collections to raise funds for the movement. In honor of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative, which celebrates the centennial of women’s suffrage in the United States, this study of female collectors, patrons, and museum founders highlights the women who made a substantial impact on the cultural advancement of their generations.

More than one of the Smithsonian Institution’s twenty-one museums owes its existence to some of the earliest women founders. In 1897, sisters Eleanor Garnier Hewitt and Sarah Cooper Hewitt opened the Museum for the Arts of Decoration (now the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum) in New York. Their grandfather Peter Cooper was the industrialist and inventor who had established the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a free school for adults, in 1853. The Hewitt sisters founded their museum as part of Cooper Union and curated its collection of drawings, prints, textiles, furniture, and decorative art objects, which they had acquired in the United States and Europe. They aimed to create a “practical working laboratory,” where students and artists could interact with the objects and be inspired by the designs.

A few years later, in 1903, Isabella Stewart Gardner opened her Boston mansion, Fenway Court, to the public. Isabella Stewart was married to the prominent banker and civic leader John Lowell Gardner, who shared her interest in art collecting and traveling. After his death in 1898, she carried out their plans to build a private museum in the style of a Venetian palace with an inner garden courtyard. In her last will, she instructed that Fenway Court (now the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum) would be for “the education and enjoyment of the public forever.”

Ultimately, Isabella Stewart Gardner amassed a collection of nearly 3,000 objects that included fine and decorative art from America, Europe, and Asia. Its treasures span classical antiquity and the Renaissance to the modern art of her own day. Not only did she collect art, but she also supported the influential art historian Bernard Berenson, who advised her collecting practice. She was also a patron of the artists James McNeill Whistler, John Singer Sargent, and Anders Zorn, who created remarkable portraits of her. Zorn’s first commission from Gardner is an 1894 etching that depicts her seated in an Italian “scabello” armchair, which appears to merge in the shadow of an opulent drapery. She is dressed in a stately, long black dress and fur mantle with a plumed headpiece that echoes the coat of arms in the background.

Like Isabella Stewart Gardner, Katherine Sophie Dreier was both a collector and a patron. Together with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, Dreier established the Société Anonyme in New York City. She later added the subtitle “Museum of Modern Art: 1920” to commemorate the year it was founded. With Duchamp’s assistance, Dreier became the driving force behind this first “experimental museum” of contemporary art in America. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, she organized and funded an extensive schedule of programs, exhibitions, and publications that featured over seventy American and international artists. In 1941, Dreier and Duchamp promised the Société Anonyme’s collection of more than 1,000 modernist works to the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven. Although Dreier was not successful in establishing an independent museum, the Société Anonyme served in part as a model for the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Around the 1930s, women patrons actively launched some of New York’s leading museums: the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. In 1929, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller invited her friends Lillie Plummer Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan to join her in founding the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), as a way to support contemporary artists. The three women selected A. Conger Goodyear as president of the board of trustees, and Alfred H. Barr, Jr. as the museum’s director. MoMA established a canonical modern art collection, which it augmented with a program of avant-garde exhibitions from America and abroad. As the museum grew, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller continued to play a pivotal role. In addition to donating over 2,000 works and providing acquisition funds, she acted as treasurer and trustee. Furthermore, she collected nineteenth-century folk art, which she gave to Colonial Williamsburg in 1939 and was transferred to the newly built Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in 1957.

by Jo Davidson, 1968 cast after

1916 original, bronze sculpture,

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Photo: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

When the Metropolitan Museum of Art turned down sculptor and patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s offer to donate her collection of modern American art, she took matters into her own hands. In 1930, she founded the Whitney Museum of American Art, contributing about 700 works to its core collection. Under its first director Juliana Force, the museum became an influential center for American art. Indeed, the founder had wanted her museum to be “devoted both to assembling the best of American art past and present and to fostering the work of living artists, particularly those working in avant-garde styles.” Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s long-term commitment to living artists is exemplified by this 1968 bronze cast after the 1916 original portrait bust, which she commissioned from the struggling young artist Jo Davidson.

A portrait commission led to the founding of another major New York City museum. The artist and collector Baroness Hilla Rebay von Ehrenwiesen, who was from an aristocratic family in Alsace, then part of Germany, had immigrated to the United States in 1927. When she painted the businessman Solomon R. Guggenheim in 1928, the two became friends and collaborators. Rebay convinced Guggenheim to begin collecting abstract art. As his advisor, she connected him to artists in Europe and eventually helped him acquire the more than 700 works that would form the basis of his museum.

In 1939, he named Rebay the first director of the new Museum of Non-Objective Painting (today the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum). Rebay curated the museum’s American and European exhibitions and wrote about and lectured on abstract art. In 1943, Guggenheim and Rebay commissioned architect Frank Lloyd Wright to build the innovative, spiraling museum building that opened in 1959. She established the Hilla von Rebay Foundation in 1967 to “foster, promote, and encourage the interest of the public in non-objective art.” Rebay’s art collection and archive became part of the Guggenheim Museum after her death that same year. A 2005 retrospective exhibition of Rebay’s artwork highlighted her pivotal role in founding the Guggenheim Museum.

©2000 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society, NY/ ADAGP, Paris

Solomon R. Guggenheim’s niece Peggy (Marguerite) Guggenheim shared his passion for abstract art, including Cubism and Surrealism. The gallerist, collector, and patron opened the Art of This Century Gallery in New York in 1942. A combined museum and commercial gallery, Art of This Century exhibited European and American artists, and gave Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko their first solo shows. During World War II, Guggenheim went even further in her role as patron and assisted many artists in their escape from Nazi-controlled areas of Europe to America.

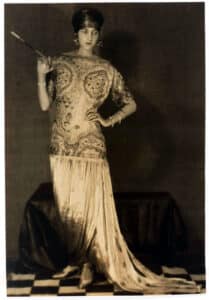

By 1947, Guggenheim decided to close her New York gallery and move back to Europe. She had spent many years on the continent becoming acquainted with the work of avant-garde artists. In 1925, she commissioned Man Ray to photograph her in a costume consisting of an elegant cloth-of-gold evening dress by Paul Poiret and a headdress by Vera Stravinsky. Another photograph from that session appeared in an article about influential foreigners residing in Paris in the Swedish weekly Bonniers Vickotidnig.

In 1948, Peggy Guggenheim was invited to display her modern art collection in its own pavilion at the Venice Biennale. She seized the opportunity to show the American Abstract Expressionists, who had never been publicly exhibited in Europe. In 1949, she moved to Venice, where she purchased an eighteenth-century palace on the Grand Canal called the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni. In forming her collection of avant-garde art, Guggenheim had consulted with the artist Marcel Duchamp and the art historian Herbert Read. In 1951, she opened the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni to the public. For her important cultural contributions, she was nominated as an Honorary Citizen of Venice in 1962. The Peggy Guggenheim Collection opened in 1980 under the management of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, to which she had bequeathed her art collection and palazzo, stipulating that the artworks remain in the Venetian residence.

Like Peggy Guggenheim, the collectors and patrons Anne Tracy Morgan and Marjorie Merriweather Post founded museums in stately residences. They also shared a common interest in French history and culture. Anne Tracy Morgan was a philanthropist who supported relief efforts for France during and after World War I and World War II. In 1929, Morgan presented France with the museum she had created in a seventeenth-century castle, known today as the Musée National de la Cooperation Franco-Américain du Château de Blérancourt. Its collection focuses on the historical, cultural, and artistic relations of our two nations from the seventeenth century to the present.

by Alfred Cheney Johnston,

1929, gelatin silver print,

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Gift of Francis A. DiMauro

In 1932, she became the first American woman to be appointed as a commander of the French Legion of Honor. The philanthropist Marjorie Merriweather Post was appointed a Knight of the French Legion of Honor for funding the construction of field hospitals in France during World War I. Post was an astute businesswoman who expanded her family’s Postum Cereal Company to form the General Foods Corporation, which she directed until 1958. She purchased the 1920s Georgian-style Hillwood mansion in Washington, D.C. in 1955, and opened it as a museum in 1977. Post hoped her rare collection of eighteenth-century French and Russian imperial fine and decorative art “would inspire and educate the public.” The Hillwood Estate, Museum, and Gardens include exceptional portraits of European and American historical figures, as well as Post’s own portrait commissions of herself and her family members.

Alfred Cheney Johnston’s photograph of young Marjorie Merriweather Post shows her great poise in a formal gown and feather headdress and veil, which she wore when received by King George V and Queen Mary at Buckingham Palace in 1929. Callot Soeurs, a woman-owned fashion design house in Paris, created her presentation at court dress.

The National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) in Washington, D.C. also owes its existence to a forward-thinking woman collector and patron. In 1981, Wilhelmina Cole Holladay and her husband Wallace F. Holladay incorporated NMWA. After renovating the historic Masonic Temple, they opened the museum in 1987. The couple had begun collecting women’s artworks in the 1960s when scholars and the public were beginning to recognize that women were underrepresented in major museum collections and exhibitions. Today, the collection includes over 4,500 works of fine and decorative art by American and international women artists that span the sixteenth century to the present. NMWA’s exhibitions, programs, and research library aim to advance women in the visual, literary, and performing arts. In 2006, Wilhelmina Cole Holladay received the National Medal of Arts from the United States and was appointed a Knight of the Legion of Honor by France.

Women did not limit their activities to Europe and cities on the East Coast. They also created museums across the United States, in addition to funding and

organizing “museums-without-walls” at fairs and international expositions and contributing to charitable organizations. Portraits played an important role in reinforcing their status as art collectors and founders of museums. One can discover further portraits and biographies of notable women in the Catalog of American Portraits (CAP). In 1966, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery founded the CAP, a national portrait archive of historically significant subjects and artists from the colonial period to the present day.

The public is welcome to access the online portrait search program of more than 100,000 records from the museum’s website: npg.si.edu/portraits/research/CAP

Related posts: