by Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

Museums, in their many forms, are a universal experience shared by most people in this country, whether it is an art gallery, natural history museum, living history museum, or historic home. Every state, city, and almost every town in America has a museum of some sort – a space that contains an assemblage of artifacts and objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance; however, the tradition of collecting and displaying intriguing items dates back thousands of years, in ways far different than we associate with today’s modern museum.

The Museum at Home

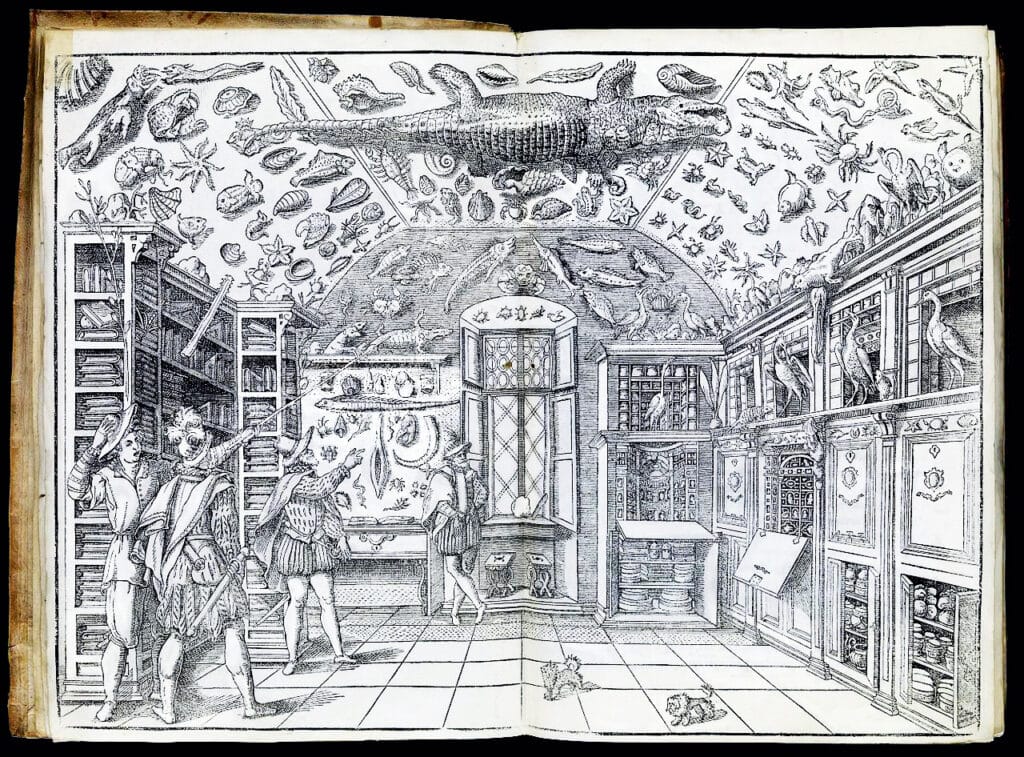

In the 18th and 19th centuries, gentlemen gained a higher social status in the world of elites by becoming a naturalist collector of specimens and curious objects. Many of the items in these early collections were new discoveries, rarities, and oddities, often displayed in so-called “Cabinets of Curiosities,” or Wunderkammer, Cabinets of Wonder, or Wonder-Rooms. Today’s glass display cases called “curio cabinets” got both their form and their name from the historic Cabinets of Curiosity.

Cabinets of curiosities were limited to those who could afford to create and maintain them. Wunderkammer first began to appear in the homes of royalty and the aristocrats in late 16th century England and Europe, where the “wonders or miracles of the world” were on display.

Cabinets exploded in popularity during the Victorian era and were a source of both learning and entertainment. The Victorians were storytellers of the natural environment and designed and displayed their Cabinets as physical representations of knowledge as well as theatre and works of art. Victorian wonders like the diorama (a miniature or life-size scene in which figures, taxidermy, and other objects are arranged in a naturalistic setting) allowed people to experience objects and specimens in situ. They were, in many respects, a fashionable prelude to the modern museums we know today; however, very few who were outside of the like-minded or “respectable” public had the ability to view these never-before-seen objects and oddities, which were mostly on display in private homes, clubs, and collections. The general public was rarely afforded the same opportunity.

As many of the early cabinet collectors—naturalists and explorers, architects and apothecaries—passed away, their collections were either donated to educational institutions, newly-formed museums of the natural histories and libraries, or they were sold to a new breed of businessman looking to start a commercial enterprise by charging admission so that others, too, could finally see these wonders of the world. The popularity of Peale’s American Museum and Cabinet of Curiosities in Philadelphia had proven the public’s willingness to pay for the novelty and entertainment of going to a museum.

Peale’s American Museum and Cabinet of Curiosities

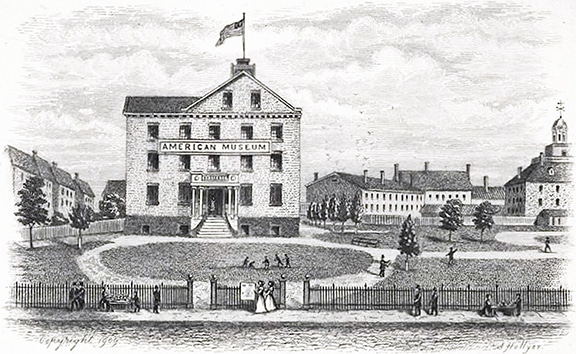

The first half of the 19th century in America saw new types of public museums springing up as tourist attractions in both big cities and small towns. For the most part, they offered a patchwork of oddities, the bizarre, art and scientific specimens, collected and displayed with no real order, agenda, or organization. One of the earliest and most noted was Charles Willson Peale’s American Museum and Cabinet of Curiosities, which opened in 1786 in Philadelphia.

The Museum was part of Peale’s determination to enlighten and educate rising generations of the New Republic. In contrast to the old elite cabinets kept by and for the well-to-do, Peale’s museum charged a nominal 25 cent admission intended to emphasize the value attached to attaining the knowledge on display while keeping it well within the means of ordinary citizens. As told in the Museum’s promotional materials, “Ever desirous to please and entertain the Public,” Peale hoped to inspire all Americans to elevate their thinking by sharing “the beautiful uniformity in a variety of things.”

An accomplished painter, Peale’s portraits of heroes of the American Revolution appeared throughout the museum, reminding American visitors of the sacrifices and triumphs of the war for independence. His establishment was among the first to include painted backdrops of landscapes and habitats of the specimens he exhibited, and his eclectic mix of the natural and the man-made included objects as diverse as an electrical machine and, by 1802, a mastodon skeleton Peale had excavated near Newburgh, New York. Thousands flocked to his museum, which he moved with great fanfare to the Philadelphia State House (Independence Hall) in 1802. By 1815, over 40,000 people visited each year. When his museum went out of business in the 1840s, P.T. Barnum eagerly snapped up items for his own museum, soon to be opening in New York City.

Scudder’s American Museum

One of the most popular museums of the early 19th century was Scudder’s American Museum in New York City, which was open from 1810 to 1841. The Museum was started by John Scudder with the acquisition of some smaller museum collections and soon relocated to a five-story building at Broadway and Ann Street where he could grow his collection and add new attractions and displays. Patrons could pay a small price to see an 18-foot live snake, taxidermy dioramas, a two-headed lamb, magic lantern slides, bed sheets from Mary, Queen of Scots, and some macabre curios like a wax figure cut by a guillotine. It was even open until 9 p.m. to wander by candlelight. The museum also had a forest scene in its large showroom with 80 stuffed animals and over 160 glass cases, with 600 specimens. In 1823, John Scudder, Jr. authored A Companion to The American Museum as a guide to his collection.

Keeping the doors of these early public museums open meant selling tickets; selling tickets meant continually introducing new attractions and exhibits to capture the public’s attention and keep them coming back for more. That took showmanship.

P.T. Barnum Enters the Ring

Foreshadowing trends in American commercial amusement, Phineas T. (P.T.) Barnum started buying up “collections” in the early 1840s to open his own brand of museum—Barnum’s American Museum—in 1841.

Early on, the Museum consisted of items from the Peele and Scudder collections, as well as other curiosity cabinets he had acquired along the way, but soon Barnum focused on commissioning new spectacles and live attractions designed to draw in the public. Barnum’s innate showmanship combined with his eclectic and ever-changing mix of live and static curiosities quickly captured the public’s attention.

To promote his latest acquisitions, Barnum turned the façade of his building (he had purchased both Scudder’s collection and the building that housed his museum) into a promotional billboard. Soon, people were lining up to see the Siamese twins Chang and Eng, tiny Tom Thumb, the skeleton of a Feejee Mermaid (made from the head and torso of a monkey with the body of a fish), a beluga whale, a flea circus, a loom powered by a dog, and the trunk of a tree under which sat Jesus’ disciples. While dubious in origin if not outright fakes, these popular attractions not only increased ticket sales but increased a city’s tourist trade.

The Museum also promoted educational ends, including natural history in its menageries, aquaria, and taxidermy exhibits; history in its paintings, wax figures, and memorabilia; and temperance reform and Shakespearean dramas in its “Lecture Room” or theater. Thus, the museum drew its audience from a wide range of social classes and strove to assure that the lecture room and salons would be one of the few respectable public spaces for middle-class women.

Before the Civil War, P.T. Barnum’s American Museum was probably the most popular in America. Imitators sprung up all over with dime museums, but Barnum was uncontested, at least until a devastating fire in 1865 that burned his Museum to the ground. Some reportedly cheered at the destruction of the sometimes-depraved museum, but most were horrified at the loss of the city’s major cultural destination. Barnum tried again with another location, but that, too, burned down in 1868, so instead, Barnum took his show of oddities and curiosities on the road, folding them under the tent of his Barnum & Bailey Circus.

As we entered the final decades of the 19th century, America’s tastes were changing. Freaks and oddities were relegated to sideshow attractions and museums became a place of knowledge and history on display. With the visitor in mind, museums began putting paintings into frames and objects on pedestals; the exhibitions themselves became less random, and text was added to guide the visitor through exhibitions. Museums also adopted the more modern form of scientific organization to their collections, which saw objects and specimens displayed in a new, properly organized context designed to inform and educate. With these new frameworks in place, both the number and types of museums in America were set to explode in the 20th century.

The Founding of America’s National Museum

Around the time Barnum’s American Museum was gaining traction, Congress established the Smithsonian Institution, the outcome of an unexpected bequest from an Englishman named James Smithson (ca. 1765-1829), who bequeathed a legacy gift to our country for the establishment of an institution for the “increase and diffusion of knowledge.”

The motives behind Smithson’s bequest remain mysterious. He never traveled to the United States and seems to have had no correspondence with anyone here. Some have suggested that his bequest was motivated in part by revenge against the rigidities of British society, which had denied Smithson, who was illegitimate, the right to use his father’s name. Others have suggested it reflected his interest in the Enlightenment ideals of democracy and universal education.

After debating using the gift to establish a library or a university, Congress instead decided that knowledge could best be increased and diffused in the new republic by creating a public museum. The Smithsonian Institution was signed into law by President James K. Polk in 1846.

The Smithsonian’s mission was to focus on scientific discovery and exhibiting objects as organized collections with a story to tell and knowledge to impart. This more scientific approach to collecting and collections stood in stark contrast to Barnum’s brand of museums as a form of entertainment, where the real, the odd, and the fake were displayed side-by-side.

From the outset, the Institute was quickly overwhelmed. Thousands of artifacts and specimens from various Washington and U.S. government collections began pouring in, in what quickly became known as the “Government’s Attic.” These included thousands of animal specimens amassed during the United States Exploring Expedition that circumnavigated the globe between 1838 and 1842 and those collected by several military and civilian surveys of the American West, including the Mexican Boundary Survey and Pacific Railroad Surveys, which assembled many Native American artifacts and natural history specimens. That was just the start of what would be decades of funding explorations and expeditions into remote parts of the world that brought back the specimens and objects that also helped to launch natural history museums in cities across the country. These collections needed to be cataloged, conserved, housed, and displayed in keeping with its charter to “increase and diffuse” knowledge. This required a bigger plan, more facilities, and a more organized and thoughtful way to tell America’s story and educate the public.

Today, the Smithsonian is the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex, with 19 museums holding the nation’s history, the National Zoo, and nine research facilities under its charter.

Museums in the 21st century

Today, there are more than 17,500 institutions throughout the United States designated as a museum, displaying art, artifacts, local history, pop culture, decorative objects, natural history, special interest collections, and anything else you can think of to more than 850 million guests annually, pre-COVID. Almost 70 percent of these museums opened after 1950, finding homes for local history collections, cultural artifacts, items from our nation’s history, presidential archives, decorative object collections, and just about anything else that reflects our national, cultural, and personal interests.

Unfortunately, with so many particularly smaller public museums dependent on ticket sales for their survival, museums across the board have been heavily impacted by the pandemic – here in America and elsewhere around the work – but like the objects they preserve and display, museums may be endangered but they are committed to the role they play in society and the stories their collections tell.

During COVID, many found new and creative ways to connect with patrons and reach new fans through virtual gallery tours, online programs, lectures, storytimes, and vlogs. These online experiences were intimate, interesting, accessible, and convenient in ways different from a physical visit. They also broke down the brick-and-mortar barriers of geography and accessibility when it comes to sharing their collections with an interested public. Now as museums re-open their front doors they are faced with finding the right balance between what they can physically and virtually provide, and what their new visitors want and are willing to pay for. Although recognizing that nothing replaces a live experience, what they may find is that the public likes options, and like everything else, that may now forever include virtual options as museums once again redefine their intent and find their audience in the 21st century.

Related posts: