by Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

A sickly child who was often confined indoors, it has been written that Teddy found joy in adventure novels and in animals. When a neighborhood vendor gave the boy the severed head off a harbor-seal carcass, an animal which at the time was plentiful in New York Harbor, Roosevelt prized the gift. He later wrote in his autobiography that preserving it felt like his own small adventure.

Roosevelt’s lifelong love of nature and conservation came from his parents, Theodore Roosevelt Sr., a founding member of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, and Martha Bulloch Roosevelt, and his father’s brother, Uncle Robert B. Roosevelt, an ardent conservationist. His family indulged his passion for nature preservation—and the dead-animal collection it produced—largely because of his childhood illnesses.

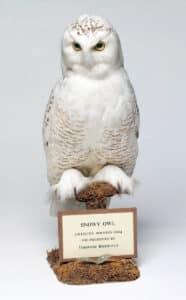

As Roosevelt’s health improved and his body grew stronger, his fascination with the natural world brought him out into the real world and in contact with things he read about, collected, and wished to study. In particular, birds. By age 12, young Teddy was studying taxidermy with an associate of John James Audubon.

In 1872, having obtained spectacles to correct his vision and a shotgun to aid in capturing specimens, Theodore traveled with his family to Egypt and Syria, where he collected numerous birds. By then a skilled taxidermist, he skinned and mounted the birds himself. If young Roosevelt’s collection methods seemed bloody and cruel, he merely followed the accepted practices of the leading naturalists of the time. Killing was the only way to make extremely accurate observations about the physical characteristics of unfamiliar animals.

When he set his sights on attending Harvard University it was largely because of the legacy of naturalist Louis Agassiz, who left behind the Museum of Comparative Zoology and a detailed system of animal classifications still used today. At Harvard, Roosevelt published his first ornithological work, The Summer Birds of the Adirondacks in Franklin County, NY. Teddy had a particular fascination with birds. Suffering from nearsightedness as a child, he had a catalog of their music in his head. He also developed strong public opinions about invasive species. During an argument known as the “sparrow wars,” Roosevelt made the case that the invasive English sparrow should be exterminated in America. His 49-page response paper to the Natural History 3 examination at Harvard in his senior year showed that he was a knowledgeable, prolific writer on the subject of birds and mammals with a promising career in the natural sciences. Instead, Roosevelt chose a career in politics; however, he never abandoned his love of nature and sense of adventure, passions he pursued both during and after his presidency.

As any collector will tell you, the thrill of the hunt can be as exciting as the acquisition itself. That was certainly the case when it came to Theodore Roosevelt. His larger-than-life adventures for the Smithsonian Institution on expeditions to collect specimens and species—everything from flora and fauna to birds, small and large mammals, insects, and sea life—from remote parts of the world are the stories on which legends are made!

Smithsonian–Roosevelt African Expedition

In 1909, shortly after the end of his presidency, Roosevelt and his son, Kermit—who served as the photographer for the adventure—embarked on a 10-month African safari, officially known as the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition. Billed as a conservation mission, this massive safari was financed by Andrew Carnegie and by Roosevelt’s own proposed writings, and outfitted by the Smithsonian, looking to collect specimens for its new Natural History Museum, now known as the National Museum of Natural History. He engaged the Smithsonian in his grand adventure by proposing the following:

“As you know, I am not in the least a game butcher. I like to do a certain amount of hunting, but my real and main interest is the interest of a faunal naturalist. Now, it seems to me that this opens up the best chance for the National Museum to get a fine collection, not only of the big game beasts but of the smaller animals and birds of Africa; and looking at it dispassionately, it seems to me that the chance ought not to be neglected.”

The unstated but recognized value-added in this arrangement was the chance for the Smithsonian to acquire specimens that had been shot by Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States.

The Smithsonian, through anonymous private donations, also funded three naturalists to join the Expedition in return for the receipt of live and preserved specimens: Edgar Alexander Mearns was selected as head naturalist and bird-collector, Edmund Heller was to care for the large mammals, and John Alden Loring was to have charge of the small mammal collecting. The party left New York on March 23, 1909, and sailed for British East Africa.

The group, led by the legendary hunter-tracker R. J. Cunninghame, started out in Mombasa, British East Africa (now Kenya), traveled to the Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of the Congo), and then followed the Nile to Khartoum in modern Sudan. For some of this journey, Roosevelt was accompanied by famed British bird-and-animal photographer Cherry Kearton, who shot wildlife and native scenes with a hand-cranked motion picture camera, later made into a movie.

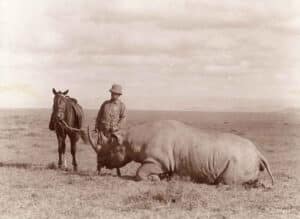

Roosevelt and his son were personally credited with killing 512 of the animals collected, including lions, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, elephants, buffalo, and (now very rare) black rhinos, and white rhinos. In his 1910 book, African Game Trails; An Account of the African Wanderings of an American Hunter-Naturalist, Roosevelt provided a complete list of their kills. He justified them by saying: “Kermit and I kept about a dozen trophies for ourselves; otherwise we shot nothing that was not used either as a museum specimen or for meat …”

The Nature Paradox

Roosevelt believed “all hunters should be nature lovers,” and hunting and preserving big-game animals held long-term value for humanity’s study of life on Earth. In his mind, “fair” hunting meant knowing natural history, knowing the land and animals, and never slaughtering for the sake of the kill alone but for the advancement of human knowledge. He condemned “game butchery as objectionable as any form of wanton cruelty and barbarity,” although he does note that “to protest against all hunting of game is a sign of softness of head, not of soundness of heart.” And as a pioneer of wilderness conservation in the U.S., he fully supported the British Government’s attempts at that time to set aside wilderness areas as game reserves, some of the first on the African continent.

Known as a Naturalist and Conservationist, this duality—Roosevelt’s love of nature juxtaposed with his passion for killing it—is perhaps the most misunderstood part of his legacy. So how does one reconcile Roosevelt’s lifelong prolific shooting of wildlife with his record as America’s foremost conservationist? Mark Twain, for one, could not; he regarded Roosevelt as a hypocrite.

The Great Amazon Expedition

Following a disappointing loss in the 1912 presidential election, Roosevelt struck out again on a scientific adventure, this time heading for South America to navigate an unmapped river in the Amazon, an adventure he described as his “last chance to be a boy.” He envisioned it as part holiday and part scientific endeavor, and again secured sponsorship from the Smithsonian and American Museum of Natural History to record and collect animal specimens on what was named the Roosevelt–Rondon Scientific Expedition.

The team consisted of Roosevelt, his 23-year-old son Kermit, two naturalists including famed American George Kruck Cherrie, a team of porters, and Brazil’s most famous explorer, Candido Rondon. Although not their original intended route down the Amazon, once in South America Roosevelt set his sights instead of traversing the mysterious Rio da Dúvida (River of Doubt), a wild and winding waterway that had yet to be charted by Europeans. His friends and family expressed concern for his health and safety with his choice of Rio da Dúvida, to which Roosevelt replied: “… I have already lived and enjoyed as much of life as any nine other men I know; I have had my full share, and if it necessary for me to leave my bones in South America, I am quite prepared to do so.”

Cherrie, a seasoned adventurer, had taken dozens of trips to Central and South America, collecting specimens for major museums. On his expedition with Roosevelt, he kept a meticulous diary, today housed at the American Museum of Natural History. It gives a day-by-day account of the daily struggles the improperly outfitted and ill-prepared expedition party faced during their 1000-mile journey down the River of Doubt. Many in their traveling party perished along the way. Roosevelt, himself, was lucky to have survived after he sliced his leg open on a rock and the wound became infected. Of the 19 men who went on the expedition, 16 returned. One died by accidental drowning in rapids (with his body never recovered), one died by murder and was buried at the scene, and the murderer was left behind in the jungle; presumably swiftly perishing there.

Cherrie and a greatly weakened Roosevelt made it home to a hero’s welcome in New York Harbor in May of 1914 with 3,000 specimens collected along the way, introducing new species never before seen outside of the Amazon, and once again making a scientific contribution to the natural sciences and natural history museums.

While Roosevelt would remember his time in the Amazon as one of his greatest adventures, it was also his last. His time in the jungle had taken its toll, and for the rest of his days he was plagued by a collection of ailments he called his “old Brazilian trouble.” The venerable “Bull Moose” stayed active and even attempted to volunteer for World War I, but he finally died in his sleep in 1919 at the age of 60.

Legacy

As President, Roosevelt set aside more federal land for national parks and nature preserves than all of his predecessors combined. He established the United States Forest Service, signed into law the creation of five national parks, and signed the year 1906 Antiquities Act, under which he proclaimed 18 new national monuments.

As a life-long Naturalist, Roosevelt’s expeditions to remote parts of the world, and what he collected and recorded along the way, introduced specimens and species never before seen outside of their native countries. These items were cataloged and studied by scientists across the natural science disciplines and put on display to the awe and fascination of visitors flocking to the new public natural history museums cropping up in cities across the country in the early part of the 20th century. His contributions in this manner helped advance our understanding of the natural sciences, while his stories and love of nature and adventure continue to fascinate and inspire future generations of naturalist collectors.

Related posts: